Owen Jones: Awful, soulless workplaces are self-defeating for the boss class, too

More than 22 million working days are lost each year to work-related stress and depression

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Those who have had a job from hell never forget it. For three months, I worked for a company that sold – if the frequently enraged customer feedback was to be believed – dodgy hearing aids. Taking phone calls from frustrated elderly people who struggled to understand my profuse apologies was bad enough: I also had to clean the earwax from rejected devices. Not that workers there could whinge about it: as workers on temporary contracts, it was made clear that we could be dropped at a moment's notice.

I'm not trying to play working-class hero here: it was a summer job from which I could easily escape, and I did. But millions of workers are in jobs that have unpleasant working conditions, lack basic rights, and even pose a threat to their health. Workers' rights is an issue that rarely worms its way into the speeches of most politicians, unlike, say, Englishness or barely inhabited islands off the coast of Argentina. This could have something to do with the fact that the most degrading job many MPs have endured is warming a toilet seat for an older classmate in a public school. But the issue gets even more marginalised at a time of mass unemployment, when those still in work are expected to feel grateful to have a job and put up with their lot, however bad it is. "A job is a job", or so the sentiment goes.

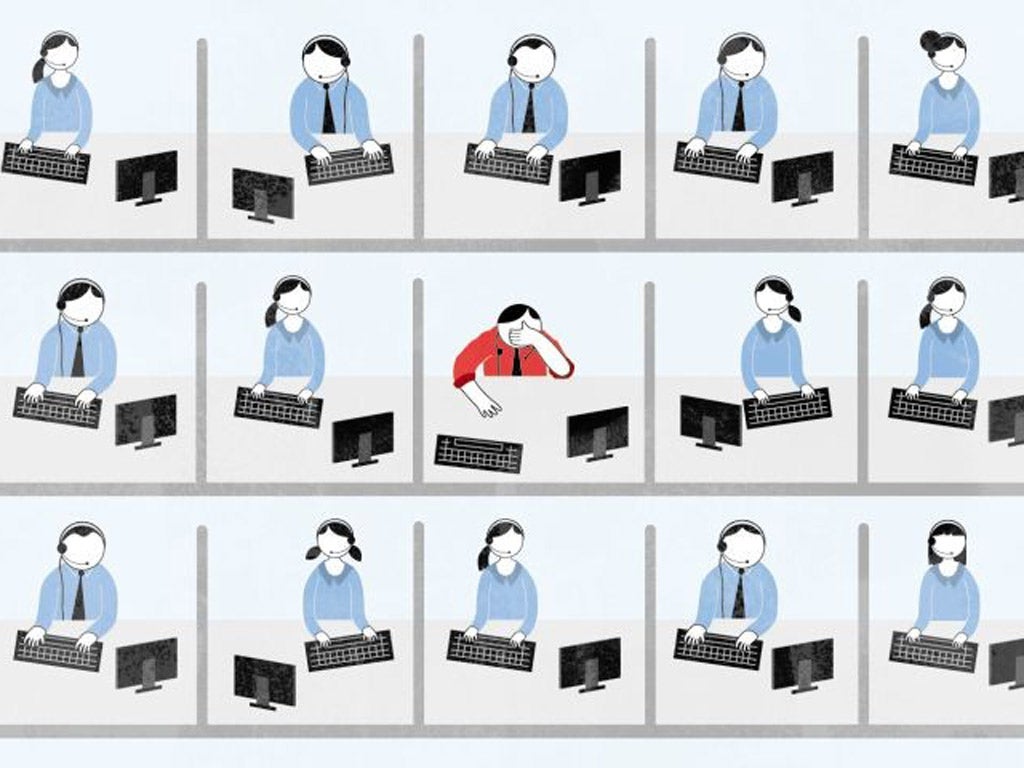

Take the plight of many call centre workers. More than a million people now work in them, which is about as many as worked down the pits at the peak of mining. This week, a survey by the trade union Unison revealed that a quarter had their access to a toilet restricted. Losing control of when you can empty your bladder is a humiliating loss of autonomy for an adult. Eight out of 10 reported suffering from stress; for nearly a quarter, it had reached the extent that it was damaging their home and personal life.

On Monday, I was inundated with tweets from call centre workers sharing their experiences. One had a four-minute per day toilet allowance; another had their use of toilet facilities monitored. One worker faced disciplinary action for taking too many toilet breaks during a kidney infection. Bear in mind that the average salary for a call centre worker is just £14,500: many are stuck at their desks for hours on end, unable to communicate with fellow workers, reading the same script over and over again, and subject to abuse from frustrated customers on a daily basis. No wonder call centres are labelled the "dark satanic mills" of the 21st century.

But just the very act of sharing these experiences was too much for some. Two Daily Telegraph writers penned attack pieces; one accused me of being Dave Spart, the satirical ultra-left caricature from Private Eye, for spending "the day, as Mr Spart would, campaigning for longer toilet breaks for call centre workers". Absurd, perhaps, but it speaks volumes about the attitude of the privileged towards basic workers' rights. Arguing that grown-ups should be trusted with basic bodily functions is apparently sufficient grounds to be dismissed as a swivel-eyed ultra-left lunatic in modern Britain.

Here is one consequence of the dramatic shift in favour of the bosses in the workplace over the past 30 years. But that work is a dehumanising experience for millions ought to be taken deeply seriously. In part, it has been worsened by Britain's lurch to a service sector economy. The old male-dominated, mucky industrial jobs had all sorts of problems, as the numbers still dying from asbestos poisoning most tragically demonstrate. But there was a sense of pride, belonging and empowerment thanks to strong trade unions that, say, a docker or steelworker felt. This is lacking in often low-paid, undervalued, transient and sometimes lonely work in supermarkets and call centres. It is poorly paid women in insecure work who suffer the most: more than two-thirds of supermarket checkout workers are women, for example, who are on not much more than the minimum wage.

The human consequences speak for themselves. It is estimated that more than 22 million working days are lost a year to work-related illnesses such as stress and depression. There are even direr health consequences from work out there. According to newly published conservative estimates in the British Journal of Cancer, 13,600 new cancer cases a year are caused by risk factors at work; of those, more than 8,000 will die as a result. It is estimated that there are 20,000 work-related deaths a year and yet – despite the fact that Britain is ranked 20th out of 34 OECD developed countries in the Health and Safety Risk Index – David Cameron is determined to rip up regulations that protect workers.

Even before the crash, work was becoming less secure – but it is as though someone has hit fast-forward on the process. The reason that unemployment hasn't (yet) surged to 1980s levels is because of the huge jump in the number forced to do part-time work; full-time work continues to plummet. On top of that, there are more than 1.5 million temporary workers who lack the same rights as others. And then there are those forced to do "zero-hour" contracts, meaning that – as one employer put it – they "may quite easily work five hours one week, none the next, and 50 the next".

I spoke to one "zero-hour" worker who had to wait for a phone call in the early hours of each day to see if he had any work. This trashing of secure work is being intentionally encouraged by big business as they exploit the economic crisis. Back in 2009, the CBI published a report entitled The Shape of Business – The Next 10 Years, calling for a smaller core workforce and a large "flexiforce": that is, workers who can be hired and fired at will. British workers are chronically overworked, too. We work among the longest hours in the EU, have the lowest number of public holidays and – according to the TUC – do two billion hours of unpaid overtime a year: enough to create over a million new full-time jobs.

Britain has some of the poorest workers' rights in the Western world, but Cameron has hired multimillionaire Conservative donor Adrian Beecroft to propose shredding those that remain. But this all comes down to power, not pity. It is not well-disposed newspaper columnists highlighting the horrors of the modern workplace that change the world, but people organising from below.

Daring to dream of a world where all workers can take a pee of their own free will might be dismissed as a Dave Spart ultra-left fantasy now. But one day, bosses may face more ambitious demands from workers than the right to control their own bladders.

Twitter: @OwenJones84

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments