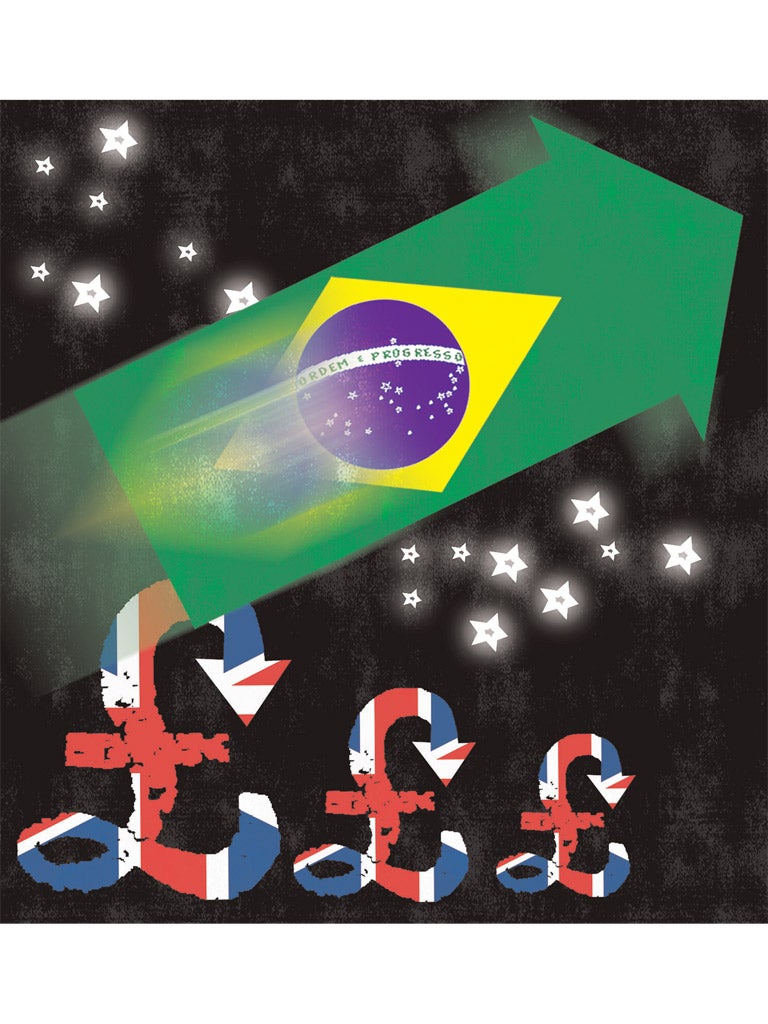

John Kampfner: Brazil's success heralds the new world order

This historic economic shift has huge implications for our sense of identity and our role in the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Pity the predictors. Forecasting the following year is a mug's game. Forecasting broader trends is easier, and one trend has surely been established beyond any reasonable doubt: the gradual but inexorable economic decline of Western Europe in general and Britain in particular.

As a report earlier this week by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) noted, Brazil has just overtaken the UK as the world's sixth largest economy. By 2020, Britain is likely also to have been surpassed by Russia and India. By 2028, Brazilians will enjoy a per capita income equivalent to ours. From 2028, barring any dramatic lurch, the standard of living of the average Brazilian will begin to be greater than that of the average Briton.

This historic shift will have huge implications for our body politic, our sense of identity as a nation and our role in the world. For the moment, international institutions remain locked in the past. The UN Security Council appears more anachronistic than ever – the victorious 1945 powers locking horns with their Cold War enemies. Although the G8 has been largely replaced by the more representative G20, the Brits and the French continue to be guided by an illusion that only the past, and their present nuclear status, provides.

By comparison, thinking in the US appears more realistic about the rise of China, the other BRICs, and by other emerging powers. In February, China displaced Japan as the second largest economy but, according to one report, the American public, precipitately, believed that the Chinese had already seized the number one spot from them.

British policy makers are mired in a combination of confusion and denial. As demonstrated by the recent debacle in Brussels over the creation of a new euro bloc with the UK on the sidelines, the Cameron government clings to the bizarre notion that somehow Britain can go it alone. According to this mythical hope, the European Union will wither away, allowing individual European nations to resurrect a 19th century-style status as global traders. Militarily and diplomatically, they cling to old notions of grandeur, fighting the good fight around the world, from Iraq to Afghanistan to Libya.

Just as the US and Europe struggle to adjust to the new dynamic, China has yet to begin to flex its muscles. Beijing and Moscow have a track record in displaying negative power at the UN – blocking resolutions that are based around human rights and other notions they habitually deride as "Western". But, while they challenge the status quo in their rhetoric, they have yet to propose an alternative model that goes beyond the idea of "no questions asked" infrastructure investment, otherwise known as the Beijing consensus.

More intriguing is the potential role for the next layer of powers, such as Brazil, the world's fifth most populous country. First under the former shoeshine boy, Luiz Inacio "Lula" da Silva, and now under Dilma Rousseff, the country has earned respect for adopting a distinctive economic and political path. Its anti-poverty drive, La Bolsa Familia –which, under the slogan "opportunity not favours", provides income support for millions of deprived families to be used exclusively for education and health – is regarded as an important paradigm for poverty alleviation. Rousseff this week reiterated her pledge to take 16 million Brazilians "out of destitution".

At least as eye opening has been the expansion of the middle class. Unlike Russia, which is almost completely dependent on natural resources, Brazil's wealth is more diversified – a mix of commodities, a strong manufacturing sector and services. Although growth is predicted to fall sharply for 2011, to 3.5 per cent, it is expected in 2012 to bounce back to the 7 to 8 per cent levels of previous years.

With that growth comes responsibilities. Under Lula's leadership, Brazil acquired some unlikely friends – Venezuela's Hugo Chavez and Iran's Mahmoud Ahmadinejad among their number. Washington was less than pleased in public, but privately Brazil's potential as a bridge was also noticed.

Under Rousseff, Brazil initially abstained from Resolution 1973 endorsing the Anglo-French "no-fly zone" over Libya. Brazil also took the Chinese and Russian line of reluctance to antagonise Bashar al-Assad in Syria. In her first year in office, Rousseff, a trade unionist tortured in the 1970s by the military junta, has continued the independent foreign policy of her popular predecessor, Lula. But the issue of human rights continues to confound emerging powers, exposing double standards – just as it has done in US and Western European policy.

What is undeniable is that countries like Brazil carry considerable weight now, particularly in the global south. A report last July by the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington urged US policy makers to stop treating Brazil and other Latin American states as subservient, as part of a Monroe doctrine that no longer exists.

The ascent to global status of not just China, but Brazil and India, followed possibly by Indonesia, Nigeria and South Africa, is in policy terms woefully under-appreciated. The Obama administration has reset its priorities, giving strong support for India and more hedged backing for Brazil in their lobbying for a permanent seat at the Security Council. With each year, the old structures seem ever more anachronistic. Psychologically, Britain has yet even to engage with the new realities. Our politicians and media continue to appeal to old notions of Churchillian endeavour, reinforced by traditional symbols of empire, the luck of speaking the ubiquitous language and London's status as the financial hub. The idea that we have any lessons to learn from the likes of India or Brazil would be regarded in many quarters as laughable.

Gradually, though, the reality will seep through. Over coming years and decades, Britain will become accustomed less to skilled workers trying to find jobs here, but to our more talented leaving for potential riches offshore. The same is happening across continental Europe, with Portuguese leaving in droves for Brazil. Britain's demotion to a middle-ranking power is already discretely recognised in foreign chancelleries, even if the language friendly foreign leaders use continues to pander to our dream world.

Militarily, UK spending as a proportion of GDP remains one of the world's highest, even after the recent tranche of cuts. But our ability to intervene, particularly in terms of boots on the ground, is waning. And, with it, a chapter in our history draws to a close.We will, whether we like it or not, eventually have to adapt, and to understand that a less bombastic role in the world is not necessarily a problem. Ask the Dutch or the Swedes.

Even though we are falling behind Brazil, India and Russia, the CEBR does offer one silver lining. Apparently, our rate of economic decline will not be as fast as that of France. Within a few years, we will pip those perfidious Frogs to ninth place in the global pecking order. Now that really is a cause for celebration.

John Kampfner is the author of 'Freedom For Sale'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

9Comments