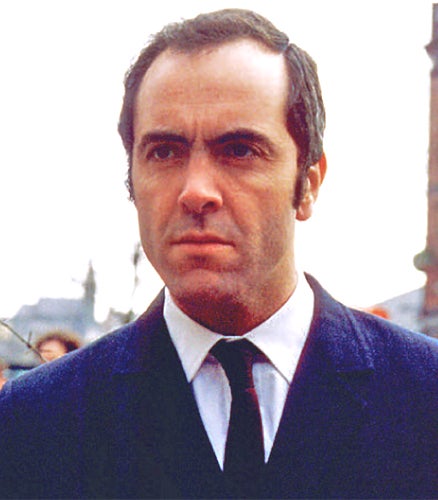

James Nesbitt: Growing up, I knew what Bloody Sunday meant

It wasn't just that without closure you can't move on from the loss: families also had a terrible sense of injustice

Making the film Bloody Sunday was important for me, not only as an actor but for my understanding of myself as an Ulsterman. It helped me realise that this episode was the watershed, and that the ensuing 30 years of conflict in Northern Ireland were in large part due to what happened that day in 1972. For it was on that night that young men all over the country joined up with the IRA in a sense of rage and injustice at what had happened.

Northern Ireland is a very small place, yet you were able to exist 30 miles away from real hotspots of conflict in relative peace and happiness. I came from a Protestant background but co-existed very easily with Catholics. Growing up, I was aware of atrocities committed on both sides and probably felt more keenly those that I thought had been visited on victims from a Protestant background. That was just the very nature of things in Northern Ireland.

I was recording Cold Feet in Manchester when the writer and director of Bloody Sunday, Paul Greengrass, and the producer, Mark Redhead, came to see me. I knew Greengrass a little socially. A lot of people of my Ulster Protestant background would have been very suspicious of the notion of a film about Bloody Sunday. Our fear would have been that it would be terribly anti-Britain and anti-soldiers, a piece of nationalist propaganda.

But I read the script and it was tightly written and balanced. I thought it interesting that Paul had chosen to put my character, the Protestant MP Ivan Cooper, at the centre of the piece. It was controversial but ultimately the right choice to place at the heart of the story a man who came from a Protestant background like my own but who as the MP for Derry had a constituent vote that was almost exclusively Catholic and who was at the forefront of the predominantly nationalist civil rights protest. I felt then that Paul Greengrass wasn't coming at the story from a particular side.

Before filming began in 2002, I went to Derry and spent the afternoon with Ivan. I asked him to tell me about the day and his memories and he spoke for hours. Then I persuaded him to do the march, which he hadn't done since Bloody Sunday because of a terrible sense of culpability.

I didn't tell Greengrass I was going over. I was worried about the fact that I, a Protestant from just up the road, was arriving in Derry to tell this nationalist story. I was worried about what the families would think, about what Derry would think, and about what my own community would think.

That night I booked into the Strand hotel in Derry. As I sat in the bar with a pint of Guinness I got a tap on the shoulder. I looked round and this guy said "Who am I?" I looked at him and said "You're Bubbles Donaghy, you were the first man shot on Bloody Sunday; you were 15 and shot in the thigh." It was something imbued in me because of all the research into Bloody Sunday that Greengrass had made me do. Donaghy reached across and said "OK, you'll do for us."

Meeting the families of the victims taught me how much of a limbo these people were in. It wasn't just that without closure you can't move on from the sense of loss – they also had a terrible sense of injustice. Widgery's original Bloody Sunday report is universally accepted as a rewriting of truth in the most terrible way. It was unquestionably a whitewash and the victims were smeared. What the families wanted was to be told that the relatives they lost were innocent and that it was murder.

I hope Saville will provide another brick in an increasingly strong wall of peace. It will hopefully close one chapter for the Bloody Sunday families and make it incumbent on the authorities to fully investigate all the unsolved killings from the Troubles. And drama has its own small part to play for there are many more stories to be told from both sides.

I think the character of Northern Ireland is now strong enough to absorb the conflicting rhetoric that will come out of all this.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks