Robert Fisk: Ottoman adventures hold lessons for our leaders

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

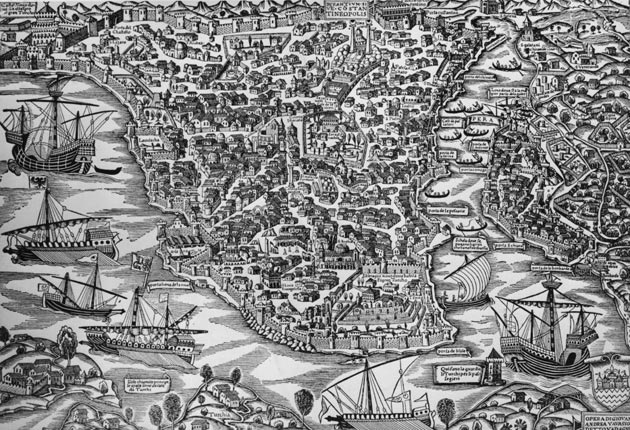

Your support makes all the difference.Amid the fury of the Arab awakening – not to mention our own deepening crisis over Libya – old Constantinople is a tonic, a reminder amid minarets and water, palaces and museums and bookshops and an ancient parliament and a thousand fish restaurants that this really was the only united capital the Arabs ever had.

The sultans used to call Beirut the jewel in the crown of the Ottomans, but two days walking the streets of modern Istanbul – its tens of thousands thronging past the old trams on Independence Street – made me understand for the first time just how tiny a place Lebanon was on the great Ottoman map. Nor can you escape the Ottomans. There in Taksim are the great old embassies of the British and Americans, below them the great banks of the powers which benefited from the "capitulations", the ancient Hotel Grande Bretagne with its crazy chandeliers, brief home to both Ataturk and Hemingway. Suddenly, I am brought up sharply by a photograph from 1917 of two Ottoman Turkish soldiers. They stand in the desert – Palestine? Syria? Arabia? – in literal rags, sack-like hats above haunted faces, their trousers hanging in strips over their legs. Oddly, there appears to be an early propeller aircraft behind them. Were these the teenagers Lawrence fought against in the Arab revolt, the precursor to the typhoon now engulfing the Middle East?

And in a bookshop by the tram stop on Istiklal, I buy Andrew Mango's life of Ataturk, more than a decade old but with the freshness of original research on the founder of modern Turkey. Yes, there are the usual weasel words about Armenian massacres ("hotly disputed", of course) but also an extraordinary account of Mustafa Kemal's early military career, sneaking through Alexandria to fight for the anti-Italian Arab rebels of – well, here we go – Libya. And there are the familiar names. Tobruk. Benghazi. Zawiya. Enver Pasha, a far darker figure in Turkish history – just ask the Armenians – was Ottoman commander in Cyrenaica, besieging Italian forces in Benghazi, dedicated to unifying the tribes of the Senussi (yes, the very same Senussi who are hoping we will win their war for them against Gaddafi) against the Italians. The Senussis, by the way, were founded by an Algerian called Muhammad Ibn Ali al-Senussi who established himself in Cyrenaica in 1843. The tribe's story, which ran up to King Idris (overthrown by a certain Colonel Gaddafi in 1969), is sharply outlined when Mango points out that "Muslim solidarity (in war) was effective when it complemented self-interest and the instinct of self-defence".

There are more paragraphs that might be read by the David Camerons of this world. There's a wonderful line in Mango's book in which he explains that "the Arabs had to be shown that the regenerated Ottoman state was capable of defending them", while Mustafa Kemal himself says of the Libyan campaign that "at the time, I myself saw that it was hopeless". One hundred and 80 Ottomans and 8,000 Arabs were able to surround 15,000 Italians but "the Arab tribesmen came and went as the spirit moved them". The main concern of the sheikhs, Mustafa Kemal discovered, was to make as much money as possible – and that the longer the war lasted, the more money they got their hands on.

At one point, Enver Pasha sent a friend of the future Ataturk to a Senussi oasis (Calo). He later wrote: "In this blessed spot even three-year-old girls are not allowed out. Females live and die where they are born. Such is the local custom. Although in military camps there are both men and women, we have not been able to see a woman's face for the last three months, as they are all hidden behind heavy veils. We lead ascetic lives... If we go on from here, our next stop will surely be paradise." Strange, though, the tricks of history. Ottoman Turkey was to ally itself to Germany three years later – Ataturk would distinguish himself at Gallipoli – and was then to crumble when Germany lost the war. Yet today, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of those same Turks are vilified in present-day Germany for having too many children, speaking little German and surviving on welfare payments. And last year, Chancellor Merkel claimed that efforts to build a "multicultural" society had "utterly failed" in Germany, a statement supported by David Cameron, who knows as much about Turkish migrants as he does about Libyan history.

For in reality, this is false history. Germany never embarked on any kind of altruistic experiment in "multiculturalism". Turks came to Germany to do the work which Germans did not want to do. The Gastarbeiter were encouraged to go to Germany to provide cheap labour rather than to act as guests in some extraordinary social programme of inter-cultural advancement; just as the first black Britons arrived after the Second World War to help to rebuild Britain – not because we wanted to give them better homes. Ataturk, of course, wanted Turkey to be European as much as Merkel and Cameron would prefer the Turks all went back to the Ottoman Empire. Maybe, however, our masters in Europe (Sarkozy, just as much as Cameron) would do well to browse through a biography of Ataturk in these heady days. The Balkan war forced the Ottomans to abandon Cyrenaica and accept the Italian annexation of Libya.

Enver Pasha refused to accept this fact of history. He argued it was "dangerous to tell Arab tribesmen that peace had been concluded". The Senussis were thus handed over to the grim mercies of the Italians, whose post-Great War fascist regime would assault them for two decades. The parallels are not exact, of course. But it would be interesting to know – if Gaddafi stays limpet-like in Tripoli – how we are going to tell our faithful "rebels" around Benghazi that Nato has run out of puff and prefers peace to more war.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments