Every year on Holocaust Memorial Day, I'll light a candle. But why?

Eleanor Margolis on her mixed feelings about Holocaust Memorial Day

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A couple of years ago, I went on a magical misery tour. My brother David and I set out on a road trip across Europe, stopping at all the important sites where, well, terrible things happened to our people.

We're Jewish, but non-practising. Just in it for the jokes, really. So I suppose we saw this as a chance to get to grips with the serious side of our culture.

On a hot summer's day, we visited Auschwitz. As we passed under the iron "Arbeit macht frei" sign, I couldn't help feeling that I was on the set of Schindler's List, rather than at a place of genuine suffering. This sense of detachment wasn't helped by the hot-dog van right outside the death camp. What a perverse Disneyland.

As Israeli schoolchildren carrying their blue-and-white flag wandered quietly through this place of Jewish pilgrimage, I thought about my own Jewish identity, and the extent to which it's shaped by the murder of six million people. And in so far as Eleanor Margolis, aged 23, of London, can do anything about Adolf Hitler, I decided to devote a small part of my 21st-century life to preserving the memory of one murdered woman.

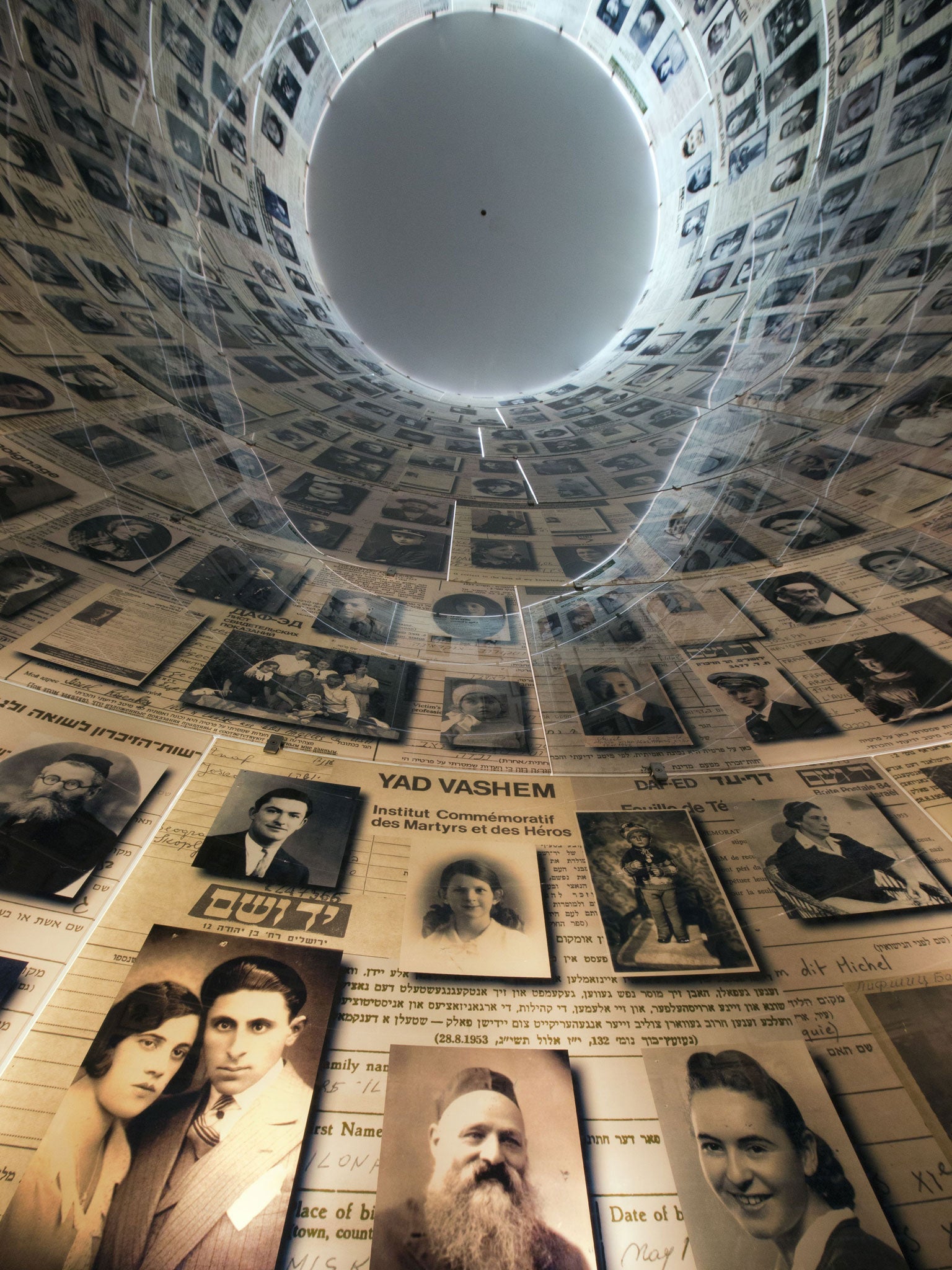

Yad Vashem, a charity dedicated to this very task, assigns volunteers a random name from their database. Josefa Gottlieber was 27 when she died in Auschwitz. This is all I know about her. Every year for the rest of my life on Holocaust Memorial Day, which is today, I will light a candle in her memory.

But how can I remember someone I never knew? In my head, Josefa was beautiful. Perhaps she had children. She was only a few years older than me when she died.

When I lit my first candle for Josefa, my dad donned the "emergency yarmulke" that he keeps in the car. My mum and I listened as he said Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, reading from a prayer book that probably hadn't been opened in 30 years. We're not religious, but as we listened to the song-like Hebrew and mourned for a stranger, we were moved.

So it seems that the only way I can truly embrace my culture is by making sure that the darkly sacred number six million continues to echo through it. But why? I feel I am part of a culture that has mourned its dead yet failed to reach acceptance, letting melancholia take over. Israel is the manifestation of this grief. To me, it's the land of the culturally wounded, where the abused have become the abusers.

So, as Israel drifts ever rightwards – last week's centrist advance notwithstanding – I wonder who I'm helping by remembering a murdered woman. I accept that as long as Holocaust survivors are alive, their suffering must be acknowledged. But, deep down, I know that clinging to the Holocaust slows progress.

And yet I've become obsessed with Josefa. I'm desperate to find out more about her and her short life. Maybe a part of me feels that she knows she's being remembered. I don't like to admit this; I'm no fan of superstition.

But when I visited Prague's famous Jewish cemetery on the Czech Republic leg of our misery tour, I saw something that disgusted me. As I walked through the site, which reminded me of a mouth crowded with crooked, grey teeth, I saw a man spit on the ground.

Perhaps he didn't realise how offensive he was being. I glared at him nonetheless. In fact, it wasn't so much a glare as a snarl.

People like him are the reason that I will unapologetically light my candle every year. In a world where the dead are literally spat on, I will show them respect even if it is a purely symbolic gesture.

And if I ever have a daughter, I'm going to give her the middle name Josefa.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments