Dominic Lawson: Who are we to decide that a dependent life is a pointless life?

Other people's sympathies are with Frances Inglis. Mine are with her son

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Three years ago this month, my wife's nephew sustained a dreadful brain injury by the banal process of falling downstairs. He was living with us at the time, on a trip from his adoptive country of Australia; so for the short period before his mother and father could make the long journey to be with him, we acted in loco parentis. We were told that the prognosis was grim.

When Dominic was first found, the ambulance paramedic performed an extraordinary operation on the spot, pushing a bolt through his skull to ease the pressure from massive bleeding on the brain. This certainly saved his life; but even after that procedure, Dominic registered at the very lowest end of the scale measuring signs of brain activity. His pupils were fixed and dilated; he had the very faintest of pulses. For some weeks we and other members of his family, and friends, kept watch by his bedside in the intensive care unit at Charing Cross Hospital. It was an agonisingly slow process, but gradually he made a recovery – and a much better one than even the most optimistic of the doctors had predicted.

Dominic went back to Australia, and completed his degree course at Sydney University. Today, at 23, he would appear to the casual observer to be as any other fit young man. His family would point out that he has some difficulties with very short-term memory, especially for faces, and as a result is more nervous about socialising with strangers – but you would never know it if you met him.

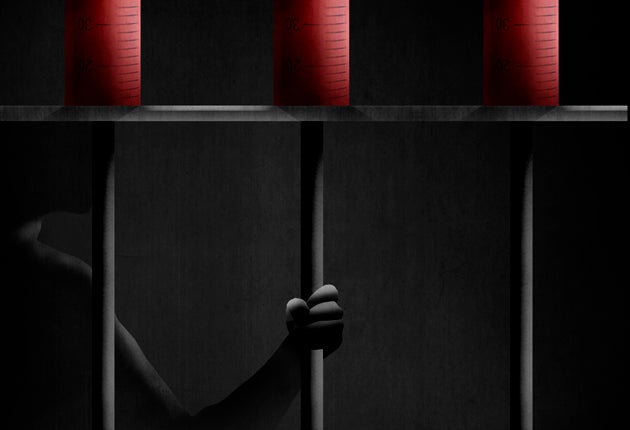

I have been thinking a lot about Dominic in the wake of the furore over the murder sentence given to Frances Inglis. Her son Tom was the same age as Dominic when he suffered a similar injury, falling out of an ambulance after an incident at a pub in July 2007. Two months later his mother tried to kill him by injecting him with heroin. He suffered a cardiac arrest, and his condition deteriorated from that point; the following year Mrs Inglis, while on bail for attempted murder, managed to inject him again. This time she was successful. Tom died.

Mrs Inglis's argument, tested by a jury last week, was that she had acted purely out of mercy, to put an end to what she saw as her son's dreadful suffering. They chose in the end to accept the words of the prosecuting QC, Miranda Moore: "This is a tragic case ... but it is not a defence to murder that a mother wants to put her son out of his misery, whether that misery was real, or, as in this case, merely perceived.... You are not entitled to terminate someone's life in this way." On conviction, the judge gave Mrs Inglis the mandatory life sentence, with a recommendation that she serve at least nine years.

This seems to have offended the entire nation – if the newspapers are to be believed. The Daily Telegraph talks of "a wave of public revulsion" at her imprisonment, the Mirror of "outrage across Britain". It's time to go back to the facts of the case. Her neighbour, Sharon Robinson, told the court that only 10 days after the initial accident, Mrs Inglis asked her to help find some heroin so that she could end her son's life – and her own: "She was mad. She was flailing her arms about. She couldn't be consoled. To Frankie, her son was dead once he fell from the back of the ambulance."

Tom's doctor, Raghu Vindlacheruvu, told the court that Mrs Inglis, a former Jehovah's Witness who seemed to have retained that sect's distinctly hostile attitude to surgical procedures, had ignored all his attempts to communicate with her about her son. He said that Tom "had little in the way of what seemed irrecoverable brain injuries. The signs were about as good as we could have had. It was possible that he could end up independent, working, self-caring. I would emphasise that this was based upon my own personal experiences of looking after young people with head injuries, not simply reading miracle stories seen elsewhere." However, Dr Vindlacheruvu went on to tell the court that after the cardiac arrest caused by Mrs Inglis's first assault on her son, his patient "never recovered to what he was like".

I don't care if the Mirror and the Telegraph are right in surmising that the entire nation is rooting for Mrs Inglis: my sympathies are principally for her son, helplessly vulnerable to his mother's deranged assaults. Tom's brother, Alex, who is furious about their mother's incarceration, told a newspaper: "You could sense Tom's emotion, you could see the panic and fear in his eyes when he tried to say something and couldn't." This was presumably an attempt to justify his mother's belief that this meant Tom wanted to die.

It seems to me equally likely that the panic and fear in his eyes was because he was unable to tell the doctors that his crazy mother was determined to kill him. There was no evidence offered that he had willed his own extermination, a clear distinction from the trial of Kay Gilderdale, who yesterday was acquitted of murdering her suicidal daughter Lynn.

One of the reasons why there seems such a public willingness to accept Mrs Inglis's actions as not only justifiable, but actually heroic, is that it is widely assumed that a dependent life is a pointless life. In the vast majority of cases, that is not the view of those in such a vulnerable position. The Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability in Putney, south-west London, is perhaps the world's leading centre in this field. One of its senior consultants told me that he has carried out psychological tests measuring self-assessed happiness among his severely disabled patients (most often the victims of traffic accidents): "Where zero is the middle of the happiness-unhappiness scale, minus five the most depressed and plus five the most euphoric, most of my patients indicate – when they are able to – that they are between plus three and plus four."

The able-bodied seem to find this hard to believe. This lack of empathy masquerading as the opposite can be very dangerous. The wholesale extermination of the handicapped which took place in Germany in the late 1930s is often seen as a purely Nazi phenomenon. Yet that policy could not have been enacted if the German people had not already indicated their acceptance of the idea of "lives unworthy of life". For example, even before this became official policy, the propagandistic film Ich Klage an! (I accuse!) had been a great hit at the German box office: it described how a court is persuaded to acquit a doctor who had administered a fatal injection to a woman with multiple sclerosis. The jury is persuaded by the doctor asking them: "Would you, if you were a cripple, want to vegetate forever?"

Fortunately, the jury at Mrs Inglis's trial at the Old Bailey last week were not convinced that such arguments should be a mother's licence to kill. I do have some sympathy with those who say that Mrs Inglis's sentence was unduly harsh. That is an argument to be had with the sentencing guidelines which judges are obliged to follow; although it is worth pointing out that had Mrs Inglis pleaded guilty to murder, rather than protest her innocence of the charge, or shown any evidence of remorse, she would according to those same guidelines have received a lighter sentence.

Yesterday I called Dominic, to tell him about this case. What did he think of the fact that the British media seemed to regard Mrs Inglis's actions as heroic? "Chilling," he said. He should know.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments