Dominic Lawson: The public want honesty, but not when it comes to their taxes

It is a myth that Churchill's 'blood, toil and tears' speech was welcome to the British

You must have had this experience: a friend asks you to give him your honest opinion about some aspect of his life – and after you've given it, you don't hear from him again for a very long time. After that, you are more than a little reluctant to oblige people with the unvarnished truth they purport to want.

Thus it is with the British public and their politicians. We like to say: "Why can't the politicians treat us like adults and tell us exactly – in complete detail – how they will reduce the national debt?" The same refrain is also the default position of leader columns in every national newspaper: Give it to us straight. When I put this a few days ago to a member of the Cabinet, his retort was immediate. There is, he said, what amounts to a free market in politics in this country: didn't it therefore occur to me that if there were a genuine and overwhelming demand for brutal frankness by politicians, then it would be supplied by at least one of the main political parties?

At the start of the year, the Conservatives did try something of the "blood, toil, tears and sweat" approach. They spoke of presiding over an "age of austerity". We were "all in it together", they added, as if to emphasise the universal inescapability of the pain to come. It did not do them much good: their opinion poll ratings, hitherto buoyant, headed south, sharpish. The Labour Party, quite predictably, described this as the augury of "massive cuts" to come... and David Cameron hastily dropped "the age of austerity" rhetoric.

You might argue there were other reasons for that drop in expressed support for the Tories, quite unconnected with the grimness of their rhetoric: it also coincided with a sense that the recession was coming to an end. A few weeks later, however, some research published by Ipsos Mori revealed what the Tories' private polling must already have indicated: that almost half the population are of the opinion that there is no need at all for government to cut its spending.

Yes, we may have a deficit unparalleled in peacetime, Labour may be spending £4 for every £3 incoming, the Institute for Fiscal studies may be telling us that by 2014 every household will have to pay an average of £3,000 a year just to pay the interest on the Government's borrowings: but these facts are not of interest, or even evident, to half the population.

There must also be millions of voters who intellectually understand the general proposition of our indebtedness as a nation, but are still loath to contemplate the radical action required to tackle it. Psychiatrists might call that "denial", and it is a fundamental aspect of human nature. It is particularly understandable during a period in which the Government, with a massive programme of printing money, is presiding over interest rates which are negative in real terms. That is bound to create a sense of economic well-being (at least among borrowers), and is hardly likely to engender the sense of crisis necessary to convince most people that harsh measures are unavoidable.

Thus it is that even the Conservatives, who had been chastising the Government for its fiscal improvidence, opened their election campaign with a pledge to revoke Labour's proposed National Insurance increase, and also ring-fenced a whole range of benefits – bus passes, winter fuel payments, TV licences – which they said they would not withdraw even from the most well-to-do pensioners. This provoked a magnificent tirade from Anatole Kaletsky, who said it was ludicrous for the Tories to claim that the national debt was of an importance overriding all other considerations-and then to propose measures which would do nothing to reduce it, but actually increase it: my old Financial Times colleague wrote that it was as if Winston Churchill had declared "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, sweat and tax cuts."

The parallel with Churchill addressing the House of Commons on 13 May 1940, three days after he became Prime Minister, is an interesting one: Churchill had not succeeded to the highest office of state via the ballot box. The Conservatives, under Stanley Baldwin, had won the most recent general election (in 1935) with a policy which we would now term "appeasement". At that time – and for some years to come – Churchill's insistence that the threat from Germany could not be negotiated away was far from popular.

Indeed, it is an enduring myth that even as Prime Minister during the war itself, Churchill's offer of "nothing but blood, toil, tears and sweat" was invariably welcome to the British people. As Angus Calder pointed out in his iconoclastic book The People's War, strikes were common, the government not especially popular, and Churchill himself an object of much public disparagement – even if that didn't find expression in the columns of the newspapers. This pent-up discontent was one reason why the great war leader received an overwhelming raspberry from the public as soon as they had a chance to express their opinion at the ballot box, in July 1945.

Churchill, admittedly, had never been completely persuaded of the benefits of the universal franchise: in 1930 he had published an essay – Parliamentary Government and the Economic Problem – which advocated its abandonment and a return to a property franchise (combined with proportional representation). I imagine that if he were dropped into our present predicament, as some political time-traveller, Churchill would argue that it is next to impossible to persuade a majority of the need for sharp public expenditure cuts, when millions of households would feel that such a policy would cost them more in benefits than they would ever get back by way of a reduction in taxes.

Just as self-interest pushes most among the rich to oppose tax increases, so a similar calculation would persuade the much less-well off not to vote for a Tory party which pledged, for example, to cut back Gordon Brown's tax credits – and there are many more of them than there are of the better-off.

If anything, the situation is even less propitious for the would-be balancer of the budget; if you were to feed the aggregate view of the British public on the appropriate balance between public services and taxation into a computer, you would probably find that a synthesised Mr and Mrs Great Britain want a public expenditure programme which would cost 50 per cent of GDP, but a tax system which would take no more of 30 per cent of national income. This, in fact, is why we need a government, rather than simply rule by the people via an endless series of plebiscites: if you want to see where that can lead, consider California - which, if it could, would already have filed for bankruptcy.

In the meantime, however, it is necessary for our next Government to become elected. And so, as the Roman satirist Juvenal – he of "bread and circuses" – observed more than 2,000 years ago, a certain amount of bribery is inevitable. Of course, the bribery is always with the public's own money, although the offers are artfully constructed in such a way as to convince the greatest number of people that it will be someone else who will pay for their goodies.

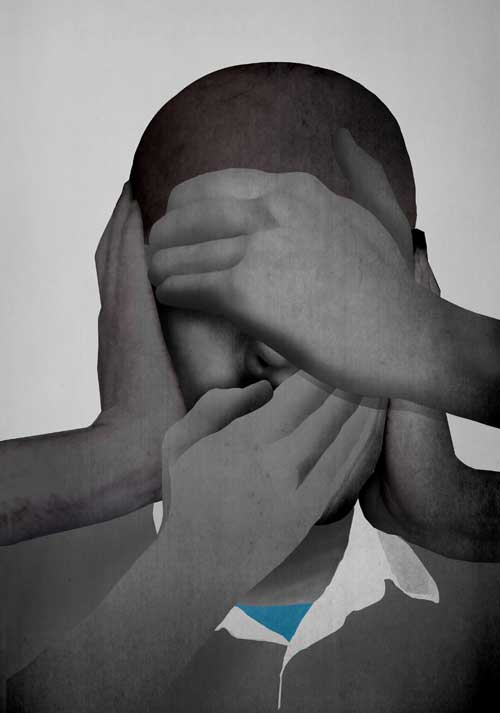

Should we blame the politicians for this? Not exclusively, by any means. As has been said often enough, under democracy the people get the governments they deserve; and thus we have become a collective Caliban, enraged at the sight of our own reflection.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks