DJ Taylor: We're all in the same boat, even old Toad

False assumptions over the poor, hard realities for university dons, 'tradesmen' in publishing and trouble down on the riverbank

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Having last week touched on the inadvisability of making jokes about chavs, the debate about what to do with the working classes (as the late Auberon Waugh might have put it) moved on to the question of "aspiration".

The Archbishop of Canterbury's remark, in a recent New Statesman, about the "seductive" distinction between deserving and undeserving poor was much quoted. Several pundits warned of the dangers of separating a huge swathe of the population into two neatly demarcated groups: on the one hand, cheery, hard-working types (when allowed) anxious to preserve their self-respect; on the other, benefit-addled layabouts rooking the state to subsidise their Special Brew.

The social, economic and quite possibly moral implications of this debate never seem to be grasped by the modern politician. For one thing, the deserving/undeserving poor distinction is bogus, as it assumes that a substantial portion of the country's worse-off citizens have no interest in "bettering themselves", to use a delightful Victorian phrase still circulating on the council estates of my father's pre-war childhood. One has to be very depressed, or inert, or nihilistic not to want a slice of the shiny consumerist cake so lavishly displayed on television each night. The question is: how to grab hold of it?

And here the modern politician will note a highly disagreeable truth, which prudence generally requires him (or her) to ignore. It is all very well coaxing several hundred thousand people off benefits, but – pace last week's employment statistics – where are the jobs? And where are they to find the skills to acquire them? The same rule applies to Michael Gove's GCSE targets. Mr Gove wants 50 per cent of students at every secondary school to get at least a C grade in five "good" GCSEs. Certain head teachers insist that the majority of the children in their care, however well taught, simply don't have the intellectual capacity to obtain these results. What is to be done about them? To what, in this bright new, hi-tech, multi-skilled 21st-century world of ours, are they supposed to aspire?

***

A survey published last week maintained that the volume of complaints about teaching standards in English and Welsh universities has risen by 35 per cent in the past academic year. This seems a lot, particularly to those of us nurtured by a university system where no one dared to complain about anything. But according to Rob Behrens, head of the adjudicator's office, the rise is attributable to a new "consumerist" attitude in undergraduates.

It is always amusing to talk to university-lecturer friends about "consumerism" in higher education. Some of its keenest proponents are not students irked at being given low grades, but the institutions superintending the process. A tutor at a university I had better not name recently lamented to me the difficulty of marking down two overseas students – whose grasp of the English language left a certain amount to be desired – beacuse his superiors were terrified of jeopardising this lucrative new income stream.

On the other hand, thinking of some of the responsibility-avoiders who slunk around Oxford college quadrangles 30 years ago, a certain amount of "consumerism" might have been a good idea. It might even have helped my best friend Mike to get his essays back from one of the college tutors before Finals so that he could have had something to revise from.

***

The news that Avon Books, part of the HarperCollins empire, has inked a deal with Sainsbury to sell certain novels exclusively in its stores has been met with a volley of criticism. The Guardian, in particular, was outraged at the prospect of a supermarket chain dictating to the public what it might read, while accusing HarperCollins (and other publishers) of a ruinous short-termism with no regard for the future of the industry or the authors who sustain it.

All quite true, of course, and yet one wonders in what fundamental regard the situation has changed in the past century and a half. As long ago as 1884, in his celebrated polemic "A New Censorship of Literature" George Moore, whose novel A Modern Lover had been refused shelf space by Mudie's circulating library on moral grounds, suggested that "at the head of English literature sits a tradesman, who considers himself qualified to decide the most delicate artistic question that may be raised, and who crushes out of sight any artistic aspiration he may deem pernicious".

But tradesmen have always run literature – the head buyer at Waterstone's exercises quite as powerful an influence as timorous Mr Mudie – and by the same token the best interests of the industry have always been betrayed by publishers. After all, practically every evil to which the modern book-world is subject – among them high discounting and the collapse of the retail base – is the result of a gang of mid-Nineties opportunists abandoning the Net Book Agreement, whereby the price on a book jacket was the amount a book sold for.

***

Radio programme of the week turned out to be a Radio 4 feature marking the 40th anniversary of Frederick Forsyth's The Day of the Jackal, in which a mysterious assassin is prevented at the last minute from putting a bullet in the head of President de Gaulle. As the programme pointed out, the secret of the novel's success was not its prose style – which, frankly, clunks – but its intimations of expertise. Even now, decades after reading it, I could tell you how to forge a passport application and, if given the appropriate materials, how to manufacture an exploding bullet.

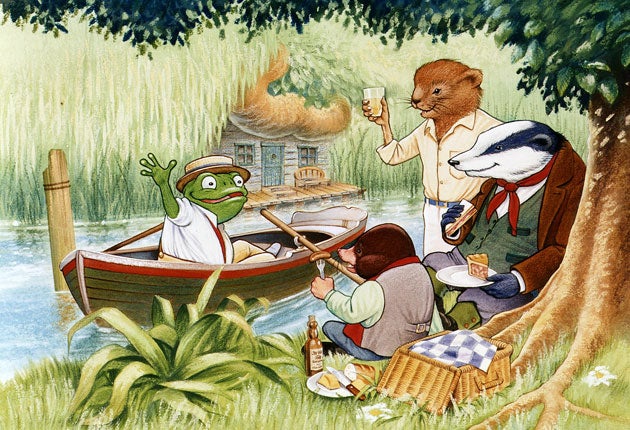

As Forsyth's example perhaps shows, half the charm of literature – and even books which scarcely count as literature at all – lies in its paraphernalia: possessions, the contents of characters' pockets, above all lists. Francis Spufford once produced a whole anthology on these lines, The Chatto Book of Cabbages and Kings, its title taken from Lewis Carroll's "The Walrus and the Carpenter" ("'The time has come', the Walrus said, 'To talk of many things: Of shoes – and ships – and sealing-wax – And cabbages – and kings.'") In much the same way, the passage in The Wind in the Willows, when Ratty dishes out the weapons before the assault on the weasel-infested Toad Hall ('"Here's a sword for the Rat, here's a sword for the Mole, here's a sword for the Toad ..."') is one of the most memorable in the whole of EngLit.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments