Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rupert and Virginia Staid were married in the early 2000s. At this point he was a stockbroker at Cazenove and she was working at the V&A.

Their honeymoon, or what Rupert called, unironically, the "wedding tour", was spent bird-watching in the north of Scotland, with occasional excursions to country houses owned by relatives of Rupert's schoolfriends. Shortly after, Rupert's uncle died and left them a sum of money so considerable, even by Staid standards, that they were able to remove themselves from the "poky" little flat in SW1 to north-west Norfolk, and set about raising a brood of miniature versions of themselves.

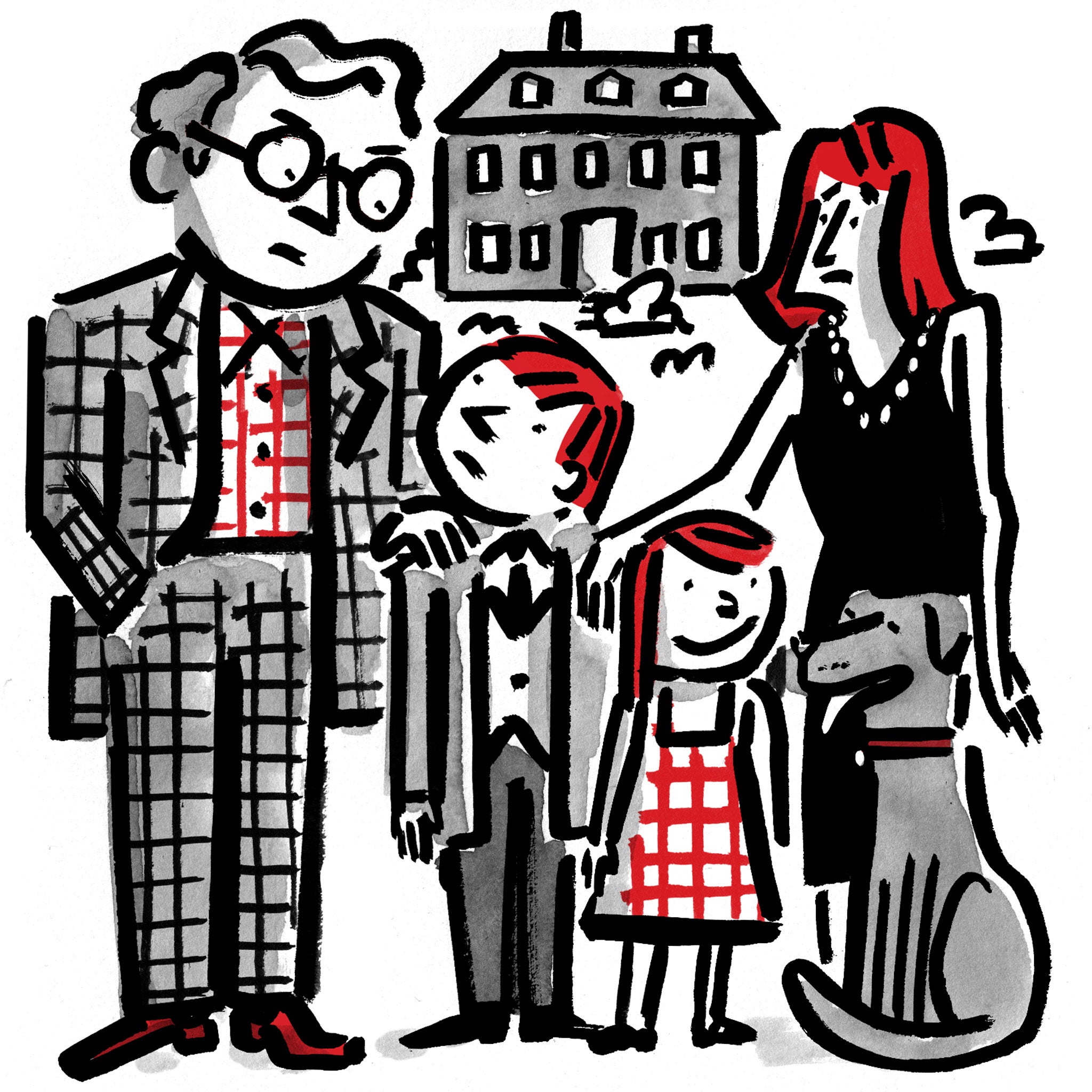

The absolute, unrepentant oddity of the Staids – an impenetrable barrier separating them from the processes of 21st-century life – is not immediately apparent. You could lunch with them at The Old Rectory, walk with a tweed-suited Rupert around the margins of his far-flung estate, listen to pearl-garnished Virginia testing nine year-old Henry on his Latin vocabulary, without ever getting to the root of this fundamental detachment. It is not that they disdain technology, comfort nor convenience – Rupert needs the internet to see how his shares are doing – simply that in a dozen different ways the modern world has conspicuously passed them by.

Some of it, perhaps, is to do with outward appearance: Rupert's blazers; Henry's short-back-and-sides; his younger sister's gingham frocks and "party shoes" in black patent leather. Some of it is to do with the old-world vocabulary (Rupert must be the last man in England to refer to a field of liquid mud as "oomski"). A bit more is to do with an ignorance, real or feigned, of practically every aspect of contemporary media. No one at The Old Rectory, for example, has heard of Lady Gaga, twerking or Spotify. These deficiencies can make conversation hard-going.

Just occasionally, cracks emerge in the façade: Rupert and Virginia go to the cinema and return bemused or scandalised; there are knowing London cousins who come at Christmas, bringing disreputable DVDs. Last week, too, there was an uncomfortable moment when Rupert, seeing his son attired in a sports jacket Virginia had procured from a mail-order firm, suddenly raised his head to remark, "You can't let him wear that. He looks like an Edwardian page boy." And mother and father stared anxiously at each other, like two ageing dodos on the Mauritian strand, heads bent over a solitary, petrified egg.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments