Christina Patterson: What Steve Jobs taught us about willpower – and its limits

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It isn't nice to want to punch someone who's dead in the face.

But, on Wednesday night, I did. On Wednesday night, when I saw a man called Steve say that he had cried when he'd read in a book that another man called Steve had paid him much less than he'd paid himself, for a job that was meant to be split 50/50, I really wanted to punch the Steve who had died, who was meant to be his friend, in the face.

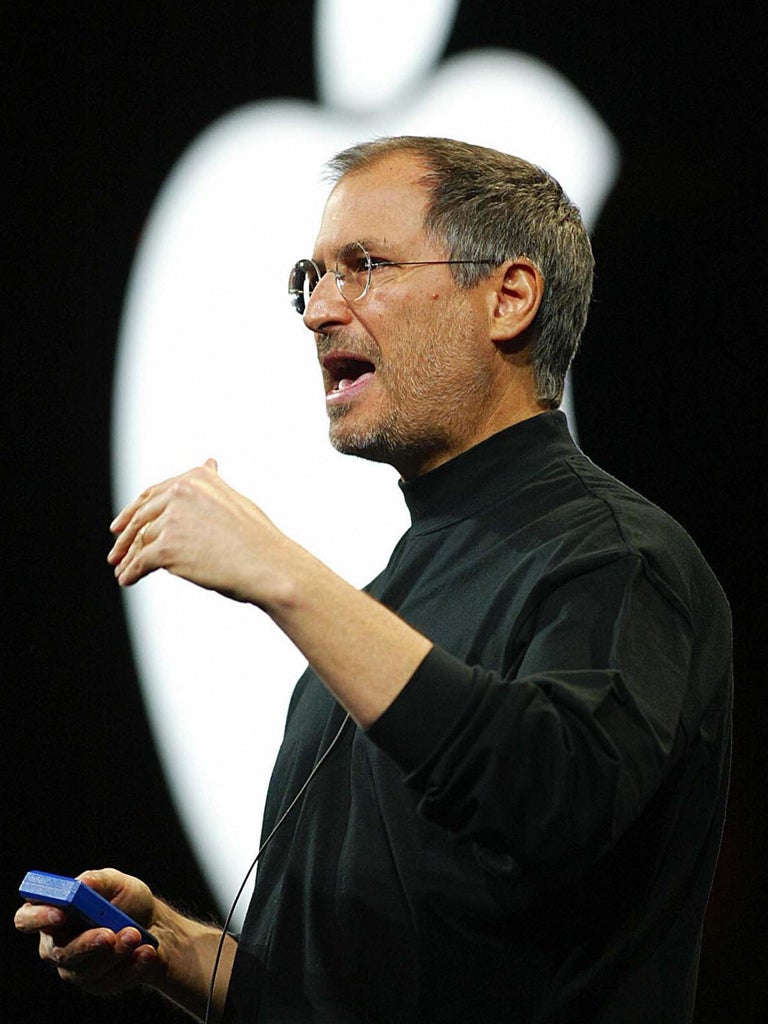

The Steve who cried was called Steve Wozniak. The Steve who had died was called Steve Jobs. Together, they founded a company called Apple. "We were pulled into business," said Steve Jobs, in a programme about his life and work. "We didn't set out to start a company." Which wasn't quite how the other Steve remembered it. "He always said," said the other Steve, "that the way you make money and get importance in the world is through companies. He always said that he wanted to be one of those important people."

What soon became clear, in this programme presented by Evan Davis (who didn't look as though he wanted to punch anyone in the face, who looked, in fact, so sympathetic that you thought maybe he should forget about the Today programme and become a psychotherapist), was that Steve Jobs was very, very ambitious. So ambitious that he thought being successful was more important than keeping promises to friends.

What also became clear was that Steve Jobs, who the programme called a "billion dollar hippy", was a bit mad. He certainly seemed, like a lot of people who wrote songs and books in the Sixties and Seventies, and, like some psychiatrists who believed the mad were sane (which didn't really help the mad people, or the sane people who had to look after them), to like the idea of being mad. He seemed to think that being a bit cray-zee was cool, and sexy, and fun. He said that his Apple Macintosh was "insanely great". He said that it was "the people who are crazy enough to think that they can change the world" who do change the world. He said that he wanted to be one of the ones who did.

Steve Jobs wasn't crazy in the way people are when they can't, for example, work out the sums in a 50/50 deal. Or in the way people are when they can't, for example, find someone else's invention, like, say, a mouse, and know that they're "sitting on a goldmine". Or when they don't know which employee to call with an idea at 2am, or which one to fire in a lift. When he shouted at colleagues in a way that was "pretty frightening for most people", that wasn't because he'd missed his morning dose of anti-psychotics. It was because he had, and liked, and wanted to keep, power.

But he was crazy in the way people are when they think their will is not just stronger than anyone else's, but stronger than the evidence in front of them, and stronger than the laws of physics. He "wasn't really fazed", said a former colleague, "in the face of depressing sales numbers" because he was so good at "imposing his own version of reality". He had, said the colleague, "a reality distortion field". He "wanted the impossible, and he was somehow able to convince everyone that the impossible was possible".

When the "impossible" is to do with changing people's minds, which you can do through marketing, and strategy, and all kinds of other things that people who are "crazy" aren't always all that good at, you can see how it might be possible to get it. But when the "impossible" is, say, beating pancreatic cancer through willpower and vegetables, and not having surgery, or at least not for a while, because you think your will is stronger than the cancer cells that are trying to kill you, it's a little bit more tricky. As Steve Jobs, too late, found out.

What Steve Jobs lived was the myth of many powerful men. It was the myth peddled by the hippies, and then by the New Agers, and also by quite a lot of the Baby Boomers, that you can bend the universe to your demands. Many powerful men cling to it because their will has won them their power. Power brings money. Money buys more power. It buys people who will put up with being shouted at, and people who never say no.

When people never say no, it's easy to think that there's no battle you can fight that you can't win. And that no harm can come your way. If, for example, you're the head of an international funding body, it's easy to think that sudden sexual encounters with chambermaids won't have any effect whatsoever on your plans to run as president of France. And if, for example, you're a mayor of Paris, who also plans to run as president of France, it's easy to think that you can siphon off public funds, for jobs that don't exist, and that no one will find out.

Most people in the world know that harm can come their way. That it can, and does, and will. And now even people in the West, who grew up thinking they could control their lives, are finding out that, because of the "reality distortion field" of a bunch of bankers, they can't.

This week, another powerful man died from cancer. But this one knew about cause and effect. "It's the fags," said Christopher Hitchens, "that will get me in the end." And, very sadly, but entirely logically, they did.

A rousing chorus of London pride

Most voices on Radio 4 sound like Libby Purves. But this week, in the "book of the week", which is something you'd only really expect to get on Radio 4, or perhaps in a nursery school, some of them didn't. This week, in extracts from a book called Londoners, there were the voices of plumbers, and squatters, and bike mechanics, and personal trainers, and even of a Wiccan high priestess.

"Someone once rang up," said the lost-property clerk in the final episode, "and said 'I left a piece of gateau on the Tube'." On this occasion, he couldn't help. But with false teeth, and gorilla suits, and suitcases full of cash, he could. "You meet a hell of a lot of good people," he says. Yes, as this mesmerising snapshot of a city of seven million reminded us, you do.

At last, a banker who's seen the light

There aren't that many people in banking you could describe as speaking up for the oppressed. But there is, I think, one. He's called Antonio Horta-Osorio and he is, though handsome, rich and successful, most famous for being "exhausted".

Being "exhausted", it turned out, when he was signed off work from his job as the chief exec at Lloyds bank, wasn't a euphemism for "executive stress". It meant crawling the walls for lack of sleep. "I understand now why they use sleep deprivation to torture prisoners," says Horta-Osorio, who was, apparently, deeply shocked to put his head on the pillow and find that sleep wouldn't come. Some of us could have told him that before. But if bankers have finally discovered insomnia, perhaps there's hope of a cure.

c.patterson@independent.co.uk // twitter.com/queenchristina_

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments