World View: The strength of Italy's new PM lies in his outsider status

Like Mr Berlusconi, he expects to charm and to get his own way

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Italy has been described as a laboratory of bad ideas – Mussolini and Fascism, Berlusconi, Beppe Grillo – but with the arrival of Matteo Renzi in Palazzo Chigi, Rome’s answer to No 10, perhaps the men in white coats have hit on something rather wonderful. Just perhaps.

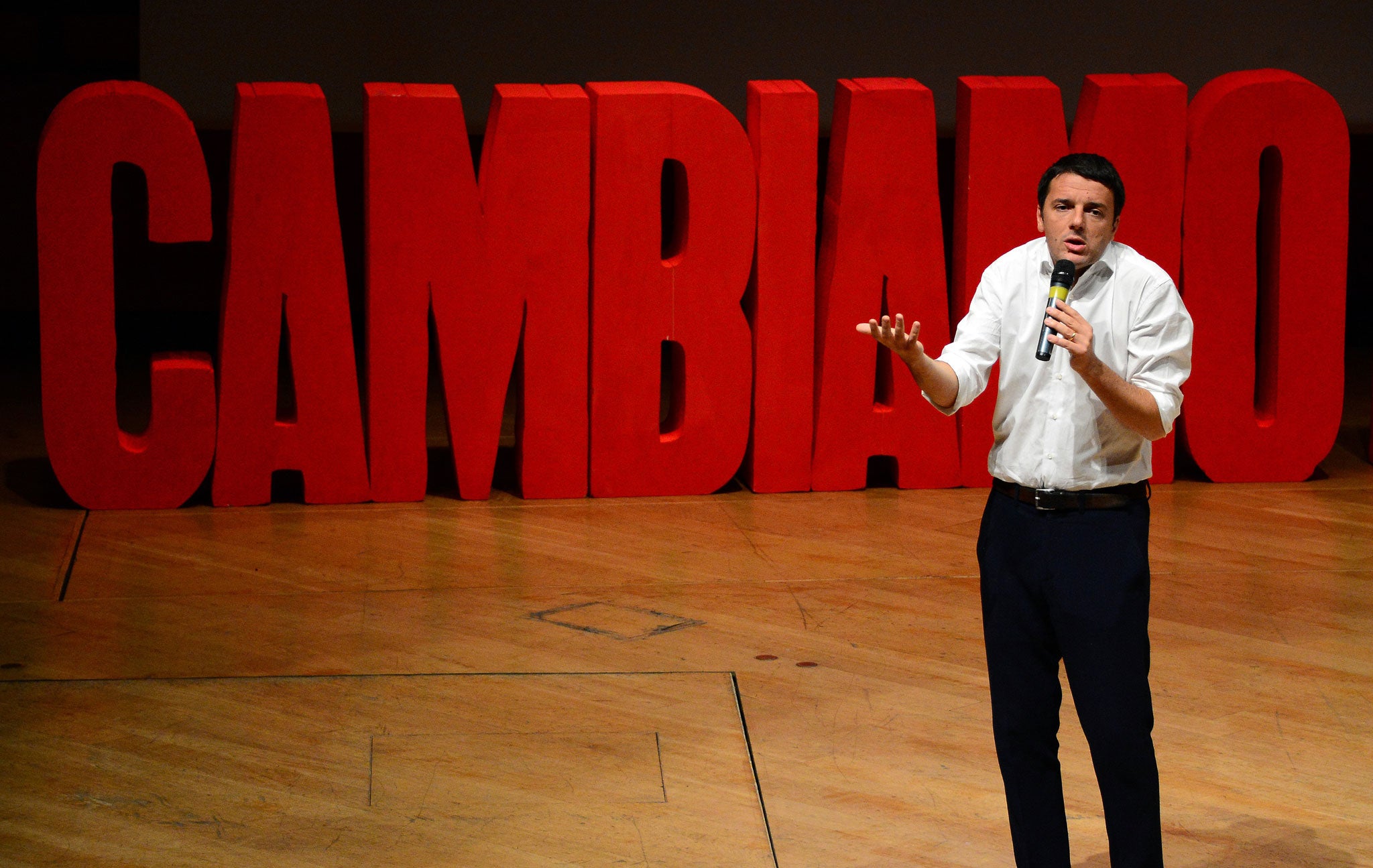

Matteo Renzi, Italy’s Prime Minister for the past 12 days, is 39 and looks at least 10 years younger, except for a couple of tell-tale strands of grey hair above his ears. He is rather large and pudgy, like an overgrown teenager, has a plump, totally unmarked face which produces two small vertical lines above his nose when he is posed a tough question, and has a pleasing way of lapsing into funny, buffoonish expressions. Likeable if bumptious, one might decide – a bit of a smarty-pants. These are mild criticisms compared to those doubtless harboured by Enrico Letta, the Prime Minister and fellow member of the Democratic Party whom Mr Renzi stabbed in the back to get the top job.

So Mr Renzi is very sure of himself, and cheerfully ruthless. Above all, unlike Mr Letta and all previous leaders of PD, he does not look tired, afraid, haunted; he does not look like an old political hack. Of the various leaves he has taken out of Mr Berlusconi’s book, that aspect of genial self-confidence is the most striking: like Mr Berlusconi, he expects to charm, to get his own way; he is not terrified of being mugged around the next corner.

Mr Renzi’s other advantage is that you do not know where to place him on the political map. The political family trees of other leaders of the Italian centre-left can be plotted with the mad precision with which ZigZag magazine used to tease out the genealogies of rock bands. Their tracks can usually be followed back to the once-mighty Communist Party or the corrupt and discredited Socialist Party, or one of the powerful trade unions.

Such a bloodline gave a leader a good chance of unwavering support from one or more of Italy’s major newspapers, all of them packed with party loyalists of one stripe or another, but by the same token it means they have to carry a lot of baggage. It means there are all sorts of lobbies they don’t dare to touch. That’s why they look in fear of their lives.

Mr Renzi’s sensational arrival in the top job was greeted by the most muted of receptions in the heavy dailies. He was not their man: they didn’t know what to make of him, or what to expect of him. All this was good, even if it did not appear so at the time. It means he is not captive to the powerful lobbies that have submerged Italy in aspic for the past several decades.

Mr Renzi is the product of a political system whose most striking contemporary aspect is its fluidity. That may sound like a good thing but it’s the result of serial failure. The collapse of the Christian Democrats and the Socialists in the corruption scandals of the early 1990s was the original failure, and yielded Berlusconi and Forza Italia. Berlusconi himself failed to do as he promised and revive the economy, and that failure eventually produced the threat of Italy going the way of Greece. But instead of galvanising the political class into a spasm of realism, as happened in Greece and elsewhere, the crisis merely persuaded the nomenklatura to cede power to the unelected dictatorship of Mario Monti, the bankers’ friend. It was a failure of courage by the political establishment for which they will pay for the rest of their careers

The proximate result was the triumph of the comedian Beppe Grillo and his Five-Star Movement, which gained one-quarter of the popular vote in the last election. This was the ultimate victory of anti-politics, but Matteo Renzi is betting on the disaffected millions who gave Mr Grillo their vote being utterly disenchanted by his behaviour since then, his brutal negation of democratic practice within the party, the tyrannical expulsion of those who cross him, including five more senators booted out this week.

Those who voted for Mr Grillo were refugees from both the right and (more numerously) the left, whom successive disillusionments had rendered politically homeless. But now they are finding that Mr Grillo’s totally negative approach to the nation’s dramatic problems is barely more satisfactory than the policies enacted by his adversaries. Something, they realise now, must be done: it is not enough, like Mr Grillo’s sinister Rasputin, Roberto Casaleggio, to conjure nihilistic dreams of a third world war followed by a brave new world ruled over by Google. You have to deal with the here and now.

That’s Mr Renzi’s trump card: his air of determination to get things done. This week the European Union said that Italy faces a “major challenge” in tackling its debt which is now more than €2trn, 132.6 per cent of GDP. Also this week, Mr Renzi, who had his first meeting as Prime Minister with David Cameron, Angela Merkel and other top EU leaders to discuss Ukraine yesterday, has promised immediate action on jobs, affordable housing and crumbling schools. Italians are wearily habituated to their leaders accomplishing very little, and taking forever about it. Some prompt and efficacious action will be much appreciated.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments