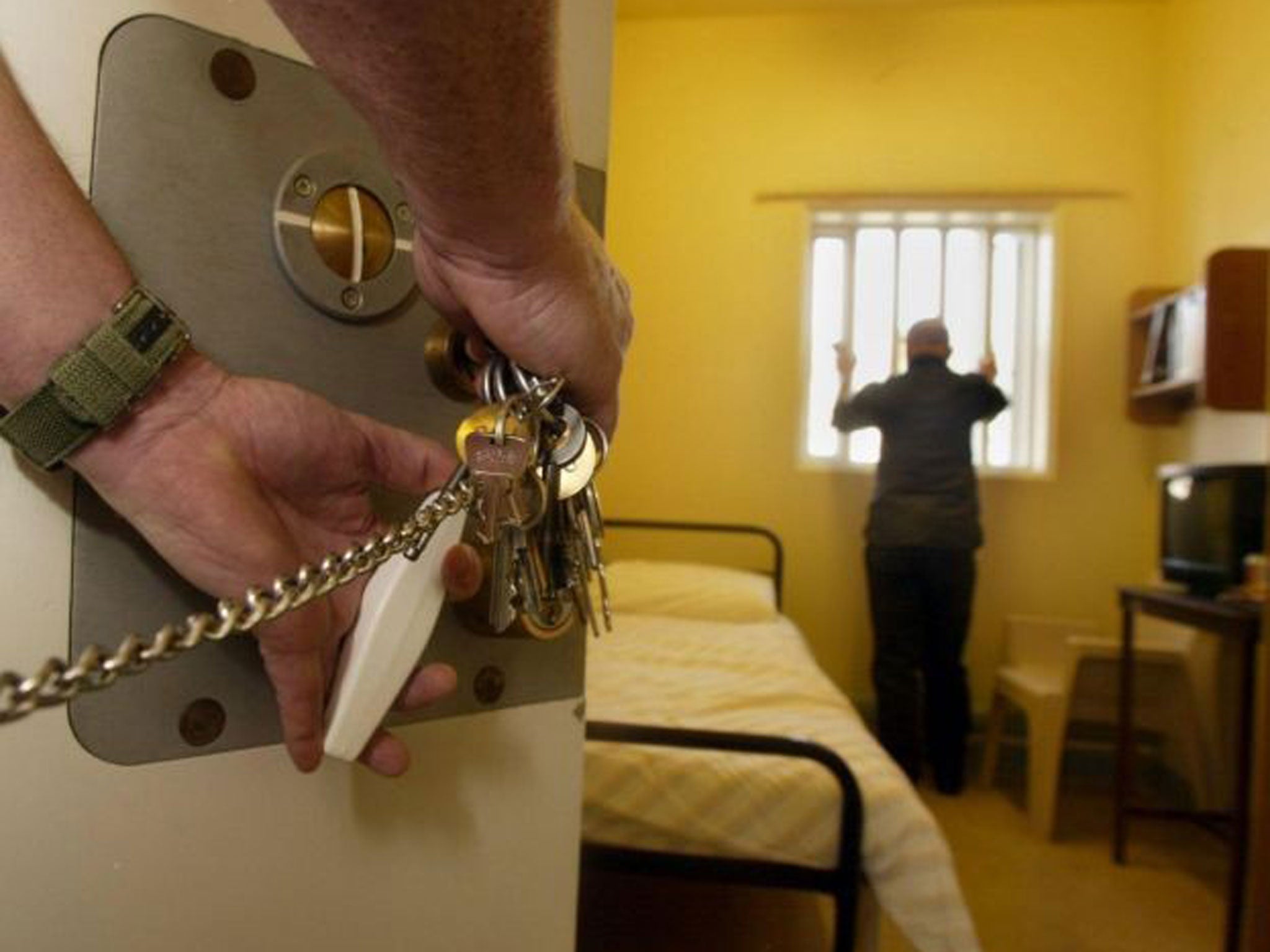

Why we shouldn't jail thieves

It would be better for society if other methods were used to punish offenders

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Imprisonment is our most severe punishment. We use it more than most other European countries and over 50 per cent more than Germany. The law says that a prison sentence should not be imposed unless the offence is so serious that neither a fine nor a community sentence can be justified. My argument is that for pure property offences like theft, handling stolen goods, criminal damage or fraud, prison should not be used; fines and community sentence should be imposed instead.

Some 21 per cent of sentenced women in prison have been imprisoned for a pure property offence, and yet report after report has considered the issue and has concluded that they should not be there. The Wedderburn Report (2000) and the Corston Report (2007) both said this in strong terms, as did the Angiolini Report in Scotland. These women do not present a danger to public safety, and they should be dealt with in the community. The same should apply to the 8 per cent of the sentenced males in prison who fit into this category.

Most of these offenders are persistent, and many have drug or alcohol problems. These should be dealt with by means of community sentences, with appropriate treatment provision and appropriate punitive elements. A well-constructed community sentence that tackles the causes of offending is much better than a prison sentence, especially when the reconviction rate of prisoners after release is well above 50 per cent. Some community sentences have had a bad press, with allegations that they are not sufficiently demanding or are not properly enforced. However, considerable strides have been made in recent years, and we should now recognise community sentences as demanding and restrictive sentences in their own right. It is wrong to regard prison as the only true punishment.

Steps should also be taken to ensure that victims do not miss out. Whilst it is unduly optimistic to think that all offenders will be in a position to pay compensation, they will certainly be in a better position to do so if they are serving a community sentence rather than in prison. The criminal justice system should look at other methods of enforcing payment, such as those used by the Department of Work and Pensions to claw back overpaid benefits.

There may be exceptional cases where prison is called for, but my argument is that the basic approach to pure property offenders – even persistent ones – should be to use compensation orders, financial penalties and, where the offence is serious enough, a community sentence. These sentences are more proportionate, more constructive, and can deliver more compensation to victims.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

11Comments