Why do we blame political apathy on politicians, when it's the people who are at fault?

We'd rather vote in Strictly Come Dancing than a general election, because we don't want to think. We'd rather just feel

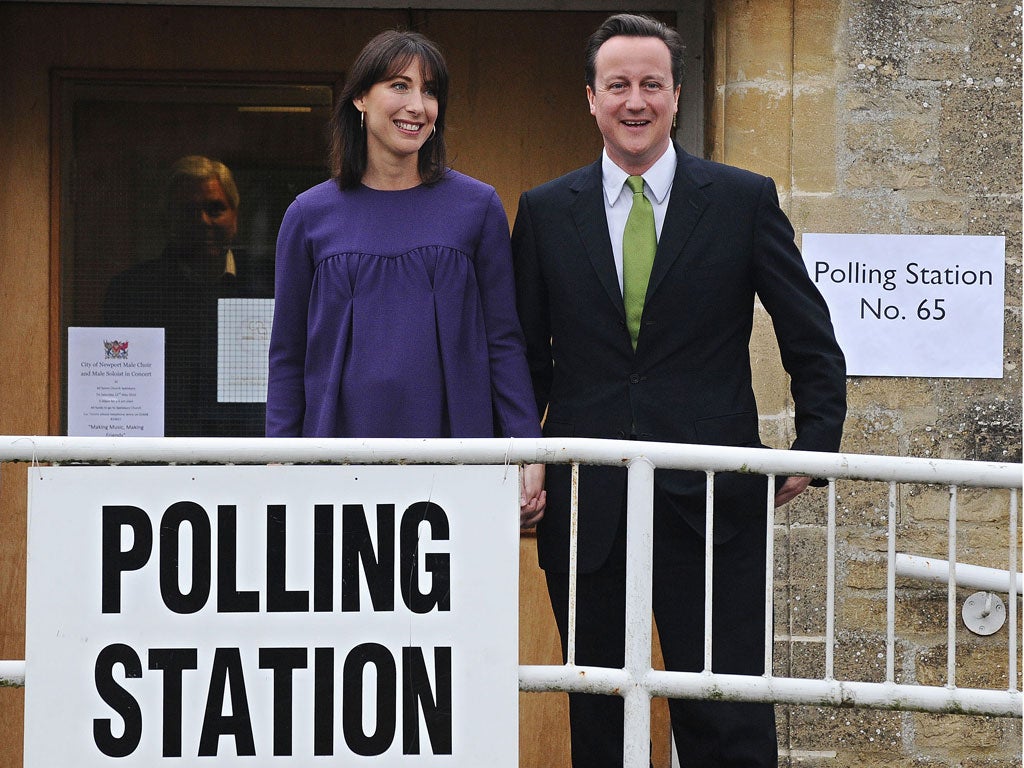

One of the odder side-effects of David Cameron’s decision to measure the nation’s wellbeing is that every new report into what makes us happy is more depressing than the last. The Office for National Statistics has been assessing the British public attitude towards the way we are governed. Predictably enough, its survey reveals a high level of disenchantment, with 79 per cent of those questioned distrusting the Government and more than three out of four people distrusting MPs generally. Asked what they liked most about Britain’s political system, 32 per cent nominated the role played by the Queen.

If that seems alarmingly dumb, worse is to follow. When those educated up to degree level were presented with the question, “Politics and government seem so complicated that a person like me cannot really understand what is going on”, a mind-bogglingly 36 per cent concurred. The figure rose to 65 per cent among those who left school at 16.

It is difficult to explain this degree of cheerful ignorance with any degree of charity. The ONS survey seems to confirm that, while even the well-educated admit without embarrassment to failing to understand political matters, they also feel able to denounce its practitioners as untrustworthy.

It matters, this disheartening combination of willed stupidity and cynicism. The very people who will be most affected in the long term by decisions being made today are those who cannot be bothered to listen to the arguments, preferring to believe the easy sneer of satirists and stand-up comedians who tell them “all politicians are the same”.

Public indifference is on the increase. During the 1970s and 1980s, an average of 25 per cent of those aged between 18 and 24 failed to vote in elections, and 19 per cent among those in the 25-34 age range. The equivalent figures for the most recent data in 2005 were 55 per cent and 47 per cent.

It is not enough to blame “the system” or the behaviour of politicians. The problem is wider and simpler than that. Political opinion requires thought and analysis, and those things have become discredited in recent years. It is emotion – instant, unthinking and effortless – which counts before anything else.

It is easier to feel good about the Queen and to feel bad about politicians than it is to think about what they represent or what they are proposing. Voting in elections requires more consideration, and is less susceptible to emotion, than voting on Strictly Come Dancing. In other words, it is not so much that politics is too difficult to understand, but that many people prefer not to try. Bleary general disaffection towards anyone in power provides the perfect get-out clause.

Sometimes, even in the culture of blame, it is not always those at the top who are most blameworthy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks