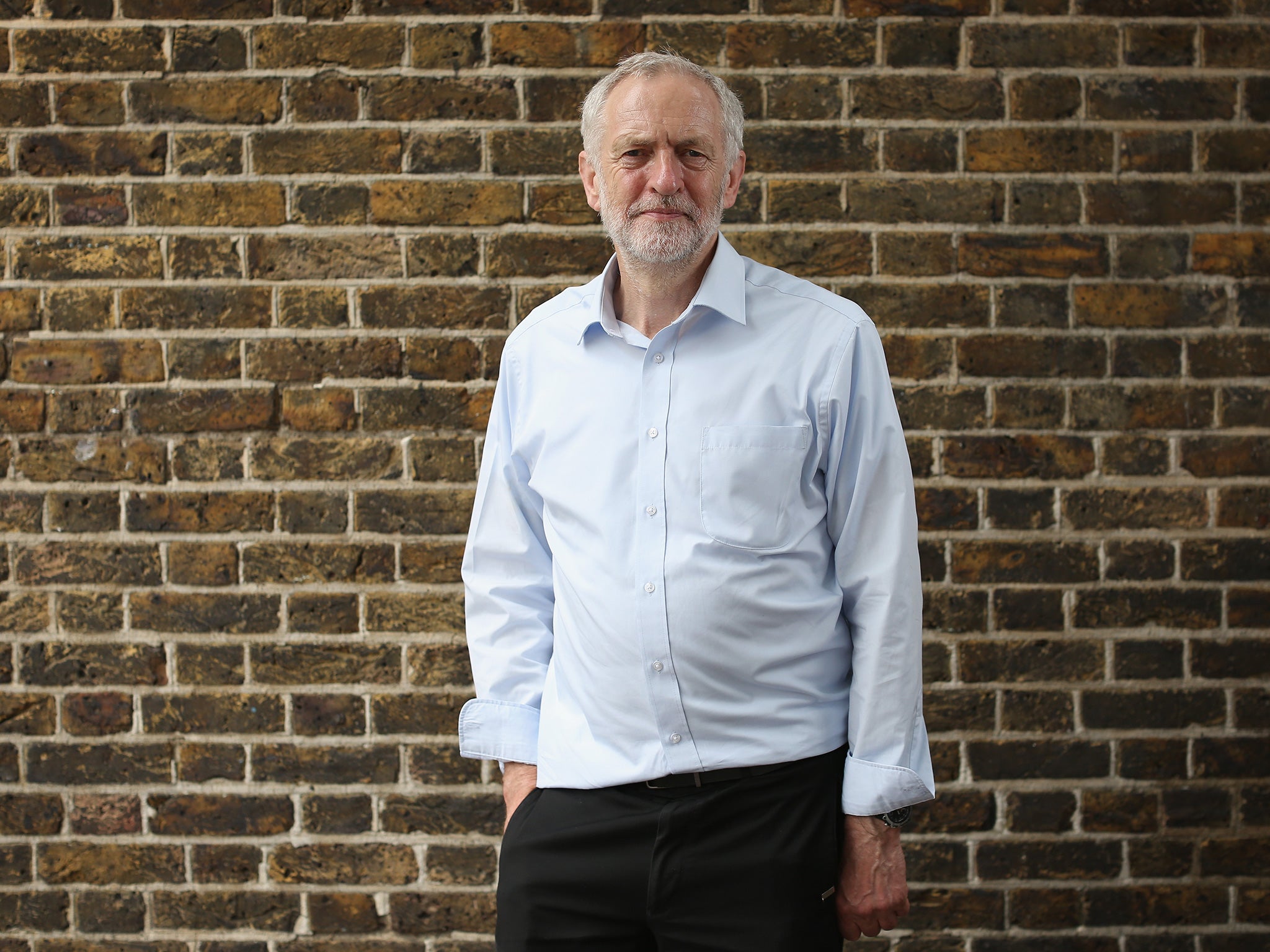

Whatever happens in the Labour leadership race, Jeremy Corbyn’s candidacy is not a calamity

It’s far better for Labour and British politics that he stood and made his historic mark

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Although many seek to do so, it is impossible to make a definitive judgement on Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership. He has not yet won, and no one knows for sure what will follow if he does. But we are in a position to make a judgement about Corbyn’s impact on Labour’s leadership contest, for that contest is almost over.

In order to make that assessment it is necessary to return to a distant world: the weeks that immediately followed Labour’s general election defeat, when Corbyn was not a leadership candidate. How easy it is to forget the sleepily vacuous post-mortems of the early phase of the leadership campaign. But I kept a note of the opening contributions from Labour’s titans, as they sought to make sense of defeat and offer bewildered party members a route towards victory in the future.

From the US, David Miliband proposed this empty route map: “We need to own the future. We turned the page back and now we must turn the page forward.”

Labour’s philosopher king, Jon Cruddas, popped up to declare: “We need to go to some dark places” in order to find out what happened. The frontbencher, Tristram Hunt, proclaimed the party must become “relevant” – as if any party has argued for “irrelevance”.

The early candidates were playing so defensively that, in their bewildered caution, they did not say very much at all. Andy Burnham’s ace card was that he was against the “Westminster bubble”. Yvette Cooper pledged “to make life better for families”. Liz Kendall suggested that one of her qualifications for leadership was that she went to school in Watford. Meanwhile, all three of them were becoming trapped in the puny, trivial and yet potentially paralysing framing of the contest by the media: would they apologise for the previous Labour government’s profligacy?

I understand that, in the aftermath of defeat, the party’s titans must speak partly in code and set out the terrain in the broadest way possible, with detail to follow later. Nonetheless, the early debate was so abstract and empty that it makes the Tory leadership contests in 1997 and 2001 seem like events of profound historic significance. It needed something to shake it up; it got a political volcano.

Without that volcano, one of those early candidates would have won to waves of indifference. Probably we would have had a re-run of the last five years: media Blairites and Tory journalists tweeting around-the-clock disdain, internal briefings of despair from Shadow Cabinet members, desperate contortions from the new leader to please critics – acts that would make him or her weaker still.

Instead there was an explosion. Corbyn is not, of course, the ideal candidate to have generated that energy and fuming controversy. He has applied for the toughest job in British politics without many of the necessary qualifications. As the economist Will Hutton noted in a talk at the Edinburgh Festival last week, Corbyn has not even sought to address the many challenges of modern capitalism; only Cooper has partially done so, Hutton said.

However, Corbyn has widened the political debate, one that – in England, at least – was stuck in a narrow, outdated place. With the rise of Corbyn, even BBC outlets feel compelled to invite on to their programmes individuals who are a few millimetres to the left of that dreary consensus – the consensus that insists public spending is a “waste”, “reform” can deliver better services on its own without adequate investment, that the only acceptable reform is an anarchic fracturing of services, that the private sector can flourish only if a smaller state keeps out the way.

For decades there has been little discussion about the purpose of government: what it can do; what it should do; and, how it should do it. In England, the debate had moved so far to the right that when Corbyn utters views, similar in some respects to those of Roy Jenkins and the SDP, he is seen as an extremist. In contrast, when David Cameron and George Osborne follow Thatcherite policies from the 1980s – from the “right to buy” to sweeping spending cuts – they are hailed by most of the media as smart centrists. If Corbyn is “extreme” for returning to the 1980s, then so too are they. This is not the ideal dance for a UK facing new challenges in 2015, but better a dance than a government tapping out its steps alone.

In response to the volcanic explosion of Corbyn’s candidacy, the other candidates and the party’s titans have raised their game. Cooper delivered her best speech of the contest when she framed her views against Corbyn’s, dissecting forensically some of his superficially argued economic policies. Tony Blair, who joined the early waffle festival with an empty speech about “comfort zones”, wrote a more thoughtful article in The Observer on Sunday, scathing about Corbyn as a leader but subtly curious about those who follow him with such fervour, and openly unsure how internal opponents should respond to them. In its nuanced dismissal it was a model for his followers who treat Corbyn and his followers only with patronising disdain.

If by any chance another candidate wins the leadership such an outcome would be a sensation now, he or she no longer greeted with a wave of indifference, as they would have been if that early soporific contest had dragged on.

Even if Corbyn wins and is out again after a disastrous, short spell as leader, he will have generated an energy that will not go away. He will have raised issues that resonate, forcing future leadership candidates to leave behind complacent banalities and think more deeply. Whatever happens next, it is better by far for Labour and British politics that Corbyn stood and made his historic mark.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments