What will drive growth? This recovery could turn out to be a flash in the pan

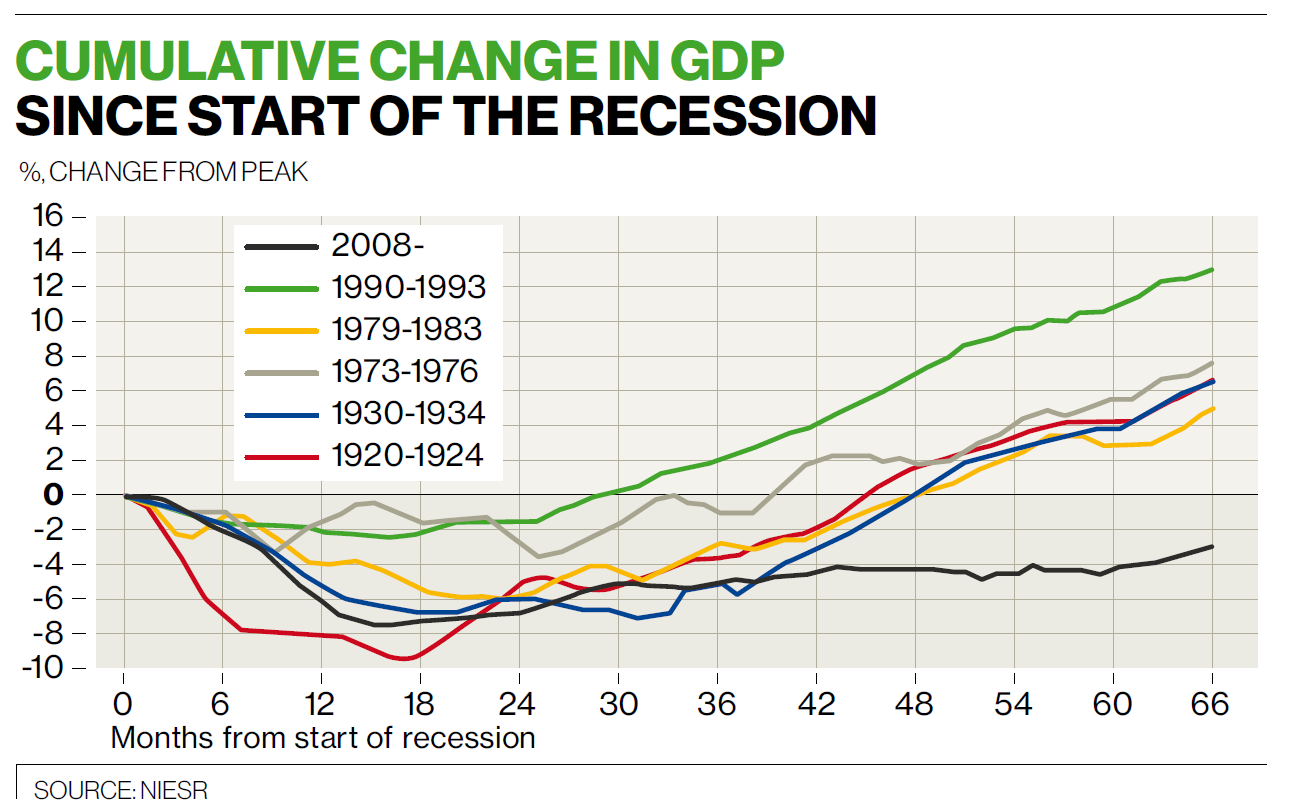

It is now 66 months since the start of the recession and GDP is still 2.9 per cent down

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I have to say I am rather surprised that the latest economic data have been so strong. Maybe Mark Carney really is a magician and everything he touches turns to gold. At long last, four years of interest rates at 0.5 per cent and £375bn of asset purchases by the MPC have started to have an effect on the real economy. There has been good news from the Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) for manufacturing, services and construction, which are a pretty good indicator of growth to come. But the employment balance in services fell for a second successive month, from 53.6 to 50.6.

A slowdown in employment growth was also evident in the manufacturing and construction surveys. This suggests that firms are meeting the upsurge in demand from existing employees rather than by taking on extra workers, which is entirely consistent with my work on underemployment with David Bell of the University of Stirling, which showed enormous pent-up demand for workers for more hours. This suggests that, at long last, productivity is rising.

Growth in the UK is likely to be closely linked to growth in the US. All eyes are now on the Federal Reserve and whether it starts tapering its $85bn-a-month programme of QE. The latest jobs data made the picture even murkier with fewer jobs created in August than expected, downward revisions to past employment numbers and a fall of 0.2 per cent in the participation rate even though the unemployment rate fell to 7.3 per cent. The big downside risk at the Fed’s meeting on September 17-18 is whether Congress is going to extend the debt limit alongside the rise in bond yields. That represents monetary tightening, and may mean the Fed will not move until the next meeting at the end of October or even later.

But it still remains hard for me to see which of the four components of growth – consumption, investment, trade and government – is going to drive growth down the road. The concern is that this is a chimera – just a flash in the pan. The latest trade data were poor so the question is whether growth will continue, or perhaps it was driven by the good weather, and the storm clouds of recession are now on the horizon. Aggregate business lending is still falling as more companies pay back loans than gain access to new credit.

Small firms in particular are still struggling to obtain finance. Consumption is being driven by dissaving, which can’t go on for that long. As a percentage of household post-tax income the saving ratio fell to 4.2 per cent in the first quarter from 5.9 per cent in the previous quarter. The OECD has upped its forecast for the UK to 1.5 per cent growth in 2013, but below the 1.6 per cent it forecasts for Japan and the 1.7 per cent for the US. But the chart, courtesy of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, allows us to put this in context. It is now 66 months since the start of the recession in 2008, and UK GDP is still 2.9 per cent below its starting level.

In contrast to the UK, many advanced countries are well above their Q1 2008 starting levels of output, including the USA (+4.5 per cent) and Germany (+3.4 per cent). The UK’s dreadful growth performance contrasts with the recessions of 1920-24 and 1930-34 when GDP was nearly 7 per cent higher after the same time period. The recession of 1979-1983 saw GDP growth of 5 per cent within five-and-a-half years. Growth has been lower in the UK since Q4 2010 than in Canada, France, Germany or the US.

It also hasn’t all been good news. August saw the British Retail Consortium’s measure of annual retail sales growth slowed from 2.2 per cent to 1.8 per cent. Plus there is still no evidence that business lending to small firms has started to pick up yet. There is every prospect that such growth as we have seen has occurred south of the Watford Gap.

Pay growth remains extremely weak. Pay deals have been in the range of 2-2.5 per cent and annual growth of earnings fell from 1.8 per cent to 0.6 per cent in June. The National Statistic Average Weekly Earnings was £473 in June 2013, exactly the same as in August 2012 and up only 1.7 per cent from its level in June 2011.

Average earnings have fallen in real terms by almost £1,500 a year, or £28 a week, since 2010. New mum Rachel Reeves, shadow chief secretary to the Treasury last week highlighted new figures showing that almost 60 per cent of jobs created since spring 2010 have been in lower-paid sectors such as retail and residential care, where median hourly pay is less than a quarter of the national hourly median.

This contrasts with the record of the last Labour government, under which such jobs made up about 25 per cent of new jobs between 1997 and 2010. It is hard to see how consumption is going to drive growth in the economy if real earnings continue to fall.

There are major regional differences in unemployment rates, with a high of 10.3 per cent in the North East and 9.9 per cent in the West Midlands compared with 6 per cent in the South East and South West. The Nationwide house price index shows that prices are nationally 11 per cent below their peak compared with 15 per cent discussed in last week’s column.

Of interest also are differences by region, with prices down by more than half in Northern Ireland and 16 per cent and 15 per cent in the North West, North and Yorkshire and Humberside. The 2013 rise in prices shows considerable variation by area, with growth close to 4 per cent in the South and below 1 per cent outside England and in the North.

In reality, emphasizing the importance of a one-size-fits-all monetary policy means the government has no regional policy. Indeed, in a written statement last September, Eric Pickles said: “The coalition government has abolished regional government”.

There is also evidence that homelessness in the UK is on the rise. The latest figures from the Office for National Statistics shows a rise of 5 per cent between April and June 2013 compared with the same quarter a year ago. The biggest increases have been in Barking & Dagenham, Newham and Waltham Forest. So regional differences matter. Maybe I was wrong and Osborne really is an economic genius, but I doubt it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments