What it's like to be gay in the world's most homophobic country

Our writer was working as an LGBTI activist in Uganda when her friend and fellow activist David Kato was murdered. Here she shares her experiences

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

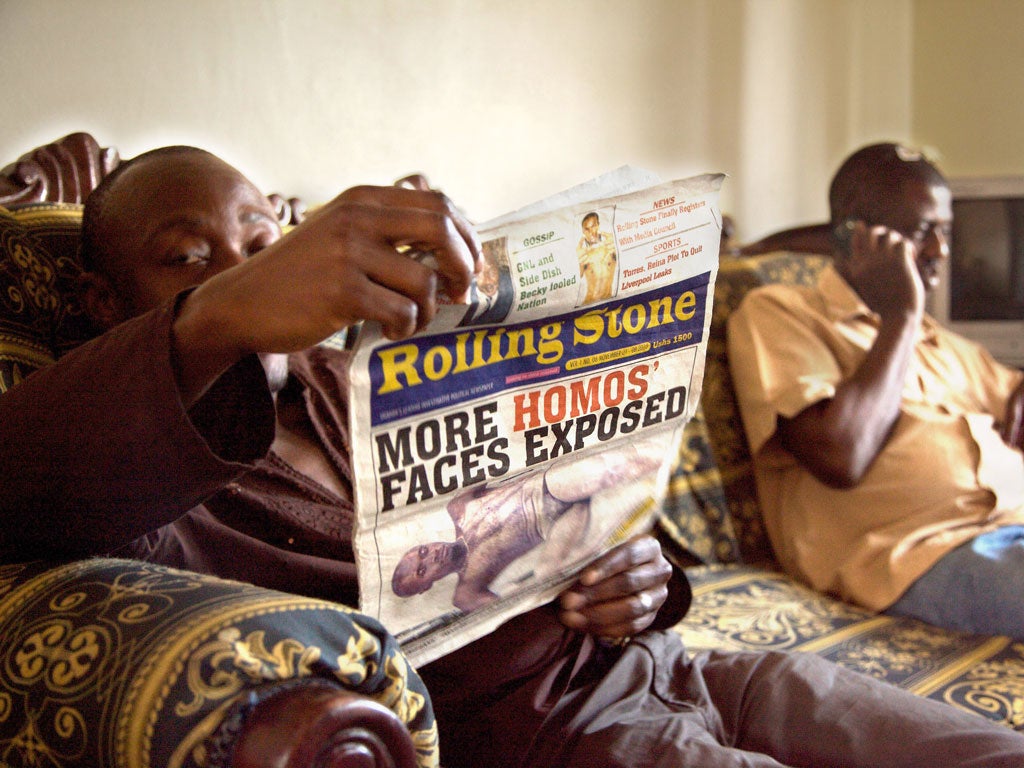

Your support makes all the difference.On 26 January 2011, David Kato was found bludgeoned to death in a street near his home in Mukono Town, Central Uganda. In the months and years before his death he had regularly been the victim of discrimination and violence; attacks which were not only permitted by the Ugandan media and government, but actively encouraged.

In 2009 the Ugandan parliament considered an Anti-Homosexuality Bill submitted by David Bahati MP introducing the death penalty for homosexuals. Following an international outcry, the Bill was postponed in 2011, but is yet to be vetoed entirely.

Call Me Kuchu, a documentary about Kato and the struggle for LGBT rights in Uganda will premiere at the Curzon Soho in London on 29 October and go on national release on 2 November. Here, Naome Ruzindana, a close friend of Kato’s and fellow LGBT activist, who also appears in the film speaks about what it’s like to be gay in one of the most homophobic nations in the world.

I met David Kato for the first time when the Queen of England was visiting Uganda. People had gathered to celebrate, but the LGBT activists including David and myself were being ejected from the space. David was among the people who left their seats first, but he called me and said you must leave that place immediately because they’re going to kill you. So I knew from then that he was really a person that felt concern for others, and he didn’t stop there. After that he was always calling me and sharing his work with me. Besides activism, we had a personal attachment. We were so, so connected in many different ways.

The news of his murder was horrible and something I never expected. David had experienced a lot of problems in the week before his death. He called me about two days before he died to tell me that he wanted to meet, but he never had enough money to come to where I was, so we were still talking about it and trying to find the money. He told me his email address had been hacked and since I’d been through the same thing a month earlier, David wanted advice. I never got any chance to talk to him again. He was killed that same week.

After David’s death the LGBT community in Uganda was kind of demoralised, but I think it was an eye opener for some of the activists too. They realised we must stand up and fight for our rights before we are all dead. It was an eye opener for me too, to know that I could really die if I don’t leave my home country.

I was born in Uganda, in a place called Toro. I grew up in a staunch Christian family and they had never seen such a thing as my sexual orientation. My mother thought I was possessed by demons, so she helped me hide it and never wanted other people to know what I was going through. In our community, young African girls will go out and play together naked and people worried that I would wanted to “check them out” and it would be strange. Every time I did anything at all they would report back to my parents and I would be punished.

I grew up hiding it because it was so strange and I didn’t even know what it was. It was only when I joined secondary school, a girls-only school that I started feeling comfortable with other girls. I had a girlfriend there, but we could never speak openly about it, even just between the two of us.

I decided to go to Rwanda after the war because I realised there was a lot that I needed to do, I needed to join activism and I had to be on the ground to lead grass roots activism. I started looking for people who were like me. I was in South Africa in 2002, I got some information from the gay people that were living there from Rwanda, they gave me the contacts of the colleagues back in Kigali, but when I met with these guys, even they did not accept me at first. They thought I was a government spy and I wanted to cause trouble. This is a legitimate fear because that’s how our government works, they have such spies who get information from you and use it against you. So I started actually going around and introducing myself. I am among the founders of the Coalition of African Lesbians, so I started giving out t-shirts, I gave out the condoms and I gave out my name. I said “If you want to, look for me on Google.” Eventually when they started seeing that I was going out and dating girls and continuing to be with them, they believed me.

I felt good when I found some people of the same sexuality as me, I felt like I was at home, but it has never been safe for me in Rwanda or Uganda. My country has always made it hard for me simply to live and operate openly. I never had my freedom of speech or my freedom of movement, I was always monitored, my phone was always tracked. I have been evicted from several different houses by landlords because of my sexual orientation. I am glad to have taken part in Call Me Kuchu , because it very accurately documents the reality of life for homosexuals in Africa. It’s a very moving film and very powerful.

When I lived in Uganda my girlfriend and I started a campaign against the Anti-Homosexuality Bill that was going on at that time, so every time they brought up the Bill my picture would be on TV and I was in danger. I had always received death threats by mail but in August 2011 I began to receive threatening voicemails, people saying that I would lose my life if I didn’t leave activism. I realised my life was really in danger and that’s when I decided to leave Africa. I’m living in Sweden now, I don’t think of going back because I’m sure they’re still looking for me and I’m sure my government is still monitoring me.

The fight for LGBT rights continues in Africa. At the moment it is focusing on documenting the injustices that have been committed and they have also launched the Hate No More campaign. The support of other LGBT activists around the world and in Britain can help and has already helped. Our president fears the international pressure. That’s when Uganda has put the Anti-Homosexuality Bill on pending. If it wasn’t for the support that we got from allies in the international community, we wouldn’t have got so far.

The Ugandan and other African activists are now really aggressive when they are speaking out against the government and defending their rights. If people wonder why, it’s because of David Kato. His death really affected us and we can’t just sit and wait for more to die.”

Call Me Kuchu will premiere at the Curzon Soho, London - 29th October with special guests co-directors Malika Zouhali-Wourall and Katherine Fairfax Wright. It goes on nationwide release on 2 November.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments