We don't all need to go to university

New 'career colleges' could reverse decades of misguided policy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

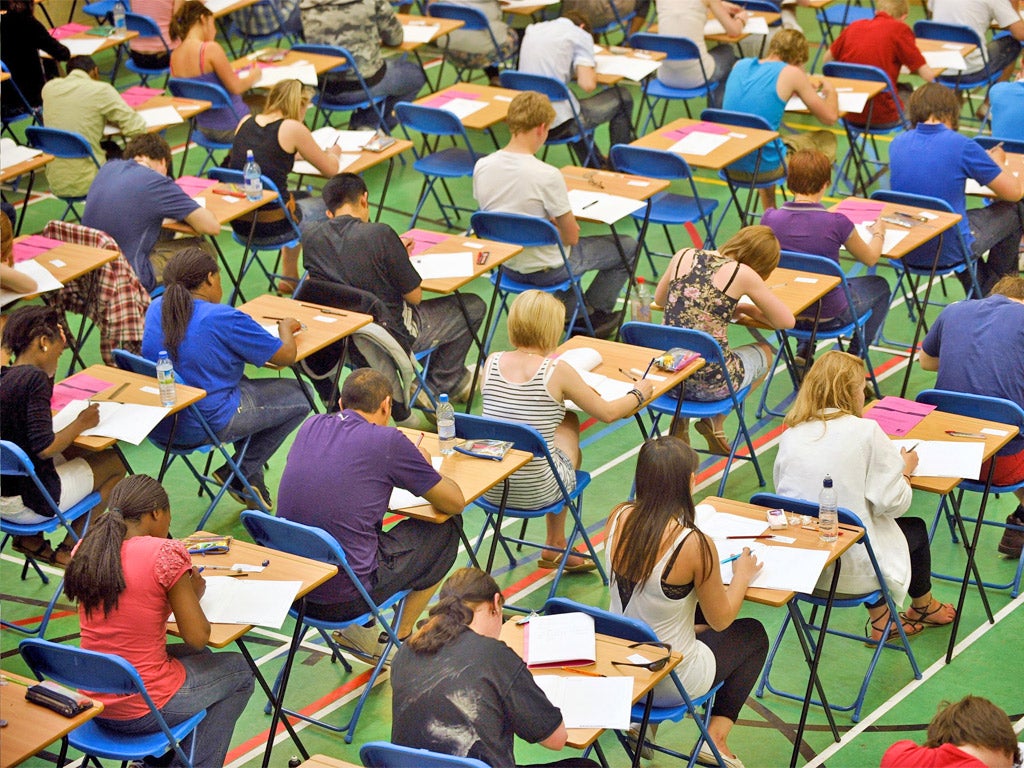

Your support makes all the difference.A couple of years ago, I was due to give a talk at a university in the north of England. When I arrived at the lecture hall, there was a sign on the door telling all the students in “hairdressing skills” that their class had been moved.

It was plain daft that anyone should go to university in order to learn how to cut someone's hair. Yet this is what was occurring.

To reach a point where something so non-academic was being taught in a supposed place of academic study and research was wrong on so many levels. It wasn't a full-time university degree subject; it should not have been taking up valuable class and teaching time; students ought not to have been expected to take out hefty loans in order to pursue the course.

The latter was the most telling point: that having to go to university to learn to become a hairdresser was bound to deter many school-leavers. While gaining letters after your name is one thing, did they really want to be rubbing shoulders with those reading history and law?

Some people are born to study, others are not. To compel those who are not to attend a university was unfair.

Once, there would have been apprenticeships available at a local salon, with possibly some formal vocational classes at a nearby technical college. Pupils could earn money as trainees while they learned the ropes and qualified. Now they were being steered to a university, which might be alien to them and they may not be able to afford.

This situation was being repeated up and down the country, in many universities and numerous subjects. As apprentice and trainee schemes had disappeared, universities jumped in to take their place. At the same time, those colleges that specialised in teaching trades themselves became universities.

A huge hole was created in our careers training, one that saw thousands that would otherwise have learned practical crafts destined for the dole, their places taken by people from overseas with those skills.

Finally, thank goodness, someone with the ear of the Government has decided to do something about it. Lord Baker, the former Conservative Education Secretary, is proposing the creation of “career colleges” aimed at 14- to 19-year-olds, to provide vocational training in all manner of subjects from web design to construction and healthcare.

In some respects, Baker's plan is not new: in recent years, specialist centres have sprung up in some industries, usually to answer the cry from employers that they lack suitably qualified recruits. But what is being devised here is broader and bigger: a network of colleges, with five well-advanced and due to open shortly.

It builds upon Baker's successful University Technical Colleges or UTCs, which focus on the so-called Stem subjects of science, technology, engineering and maths. There are 17 UTCs in existence, with a further 27 on the blocks.

But the Baker scheme, endorsed wholeheartedly by the new minster for skills, Matthew Hancock, is only part of the solution. We need to change mind-sets, to convince parents, their children and schools, that university is not the only answer.

Somehow we've become obsessed with the notion that university is everything. We've got too many universities offering too many courses to too many students. That has to change.

It wasn't that long ago that obtaining a degree was regarded as akin to a higher calling, available to only the few. While no one would advocate returning to that, a halfway is preferable, in which if someone wants to get on in work without becoming a graduate, society does not think less of them for doing so.

That's where we are, right now: too much snobbishness is attached to the securing of a Bachelor or Masters in this or that. When I was at my grammar school, in an industrial town in the north, some boys stayed on at 16 and others left for employment. It never occurred to me or my friends to look down on them – if anything we were jealous as they were the ones with leather jackets, motorbikes, pay packets and girlfriends.

At 18, one lot went to university, polytechnic or teacher training college, the rest became management trainees at those same factories and shipyard or banks, building societies and store chains.

There was no yawning divide, no feeling of them and us. The same was true of the girls in the town. At university holidays, we still carried on mixing together, seeing each other, even though one group was away much of the time and the others had stayed put.

Somewhere, down the decades, an edge was inserted, the sense was allowed to develop that one mob mattered and the rest didn't. It started to go wrong with the government of James Callaghan in 1978, and the introduction of the Youth Opportunities Programme. The YOP system was expanded by Mrs Thatcher when she came to power; then, in 1983 she replaced it with the Youth Training Scheme or YTS.

The YTS was aimed at 16- to 17-year-olds and was supposed to provide on-the-job training leading to a career. In fact, it was no substitute for the craft apprenticeships that were fast disappearing and acted as a source of cheap, unskilled labour.

When Baker became Education Secretary in 1986, the damage was being done. Now, he's back with a new system. It can't be coincidence that one aspect of his career colleges will be continuing education. Pupils will study English, maths and science at GCSE, as well as their vocational choices. At the UTCs, the syllabus mix is 40 per cent vocation, 60 per cent academic.

At last, we're moving in the right direction. It's just a pity it's taken so long and so many incomplete or valueless degrees, and so much wasted money, in order to get there.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments