US debt: The rise of America’s vetocracy is true to the ideals of the Founding Fathers

In a system designed to empower minorities and block majorities, stalemate will go on

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

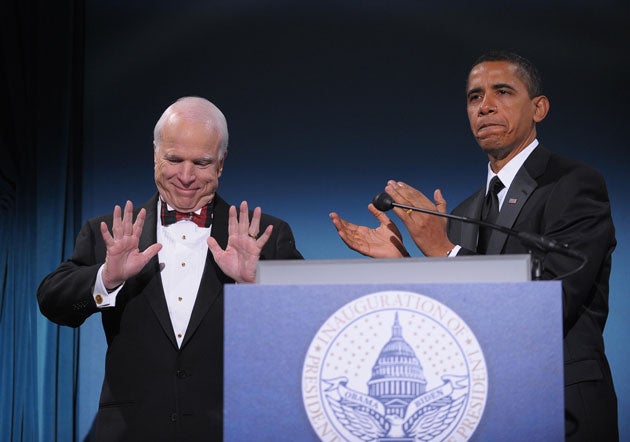

Your support makes all the difference.The House Republicans’ willingness to provoke a government shutdown as part of their effort to defund or delay the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, illustrates some enduring truths about American politics — and how the United States is an outlier among the world’s rich democracies. As President Obama asserted, America is indeed exceptional. But that’s not necessarily a good thing.

The first way America is different is that its constitutional system throws extraordinary obstacles into the path of strong political action. All democracies seek to balance the need for decisiveness and majority rule, on the one hand, and protection against an overreaching state on the other. Compared with most other democratic systems, America’s is biased strongly toward the latter. When a parliamentary system like Britain’s elects a government, the new leaders get to make decisions based on a legislative majority. The United States, by contrast, features a legislature divided into two equally powerful chambers, each of which may be held by a different party, alongside the presidency. The courts and the powers distributed to states and localities are further barriers to the ability of the majority at the national level to get its way.

Despite this dissipation of power, the American system was reasonably functional during much of the 20th century, both in periods when government was expanding (think New Deal) and retreating (as under Ronald Reagan). This happened because the two political parties shared many assumptions about the direction of policy and showed significant ideological overlap. But they have drifted far apart since the 1980s, such that the most liberal Republican now remains significantly to the right of the most conservative Democrat. (This does not reflect a corresponding polarisation in the views of the public, meaning that we have a real problem in representation.) This drift to the extremes is most evident in the Republican Party, whose geographic core has become the Old South.

As congressional scholars Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein have pointed out, this combination of party polarisation and strongly separated powers produces government paralysis. Under such conditions, the much-admired American system of checks and balances can be seen as a “vetocracy” — it empowers a wide variety of political players representing minority positions to block action by the majority and prevent the government from doing anything.

American vetocracy was on full display this past week. The Republicans could not achieve a simple majority in both houses of Congress to defund or repeal the Affordable Care Act, much less the supermajority necessary to override an inevitable presidential veto. So they used their ability to block funding for the federal government to try to exact acquiescence with their position. And they may do the same with the debt limit in a few days. Our political system makes it easier to prevent things from getting done than to make a proactive decision.

In most European parliamentary democracies, by contrast, the losing side of the election generally accepts the right of the majority to govern and does not seek to use every institutional lever available to undermine the winner. In the Netherlands and Sweden, it requires not 41 per cent of the total, but rather a single lawmaker, to hold up legislation indefinitely (i.e. filibuster). Yet this power is almost never used because people accept that decisions need to be made. There is no Ted Cruz there.

The second respect in which America is different has to do with the virulence of the Republican rejection of the Affordable Care Act. Every other developed democracy — Canada, Switzerland, Japan, Germany, you name it — has some form of government-mandated, universal health insurance, and many have had such systems for more than a century. Before Obamacare, our health-care system was highly dysfunctional, costing twice as much per person as the average among rich countries, while producing worse results and leaving millions uninsured. The health-care law is no doubt a flawed piece of legislation, like any bill written to satisfy the demands of legions of lobbyists and interest groups. But only in America can a government mandate to buy something that is good for you in any case be characterised as an intolerable intrusion on individual liberty.

According to many Republicans, Obamacare signals nothing short of the end of the US, something that “we will never recover from,” in the words of one GOP House member. And yes, some on the right have compared Obama’s America to Hitler’s Germany. The House Republicans see themselves as a beleaguered minority, standing on core principles like the brave abolitionists opposing slavery before the Civil War. It is this kind of rhetoric that makes non-Americans scratch their heads in disbelief.

But while the showdown over the Affordable Care Act makes America exceptional among contemporary democracies, it is also perfectly consistent with our history. US constitutional checks and balances — our vetocratic political system — have consistently allowed minorities to block major pieces of social legislation over the past century and a half. The clearest example was civil rights: For 100 years after the Civil War and the passage of the 13th and 14th amendments, a minority of Southern states was able to block federal legislation granting full civil and political rights to African Americans. National regulation of railroads, legislation on working conditions and rules on occupational safety were checked or delayed by different parts of the system.

Many Americans may say: “Yes, that’s the genius of the American constitutional system.” It has slowed or prevented the growth of a large, European-style regulatory welfare state, allowing the private sector to flourish and unleashing the US as a world leader in technology and entrepreneurship.

All of that is true; there are important pluses as well as minuses to the American system. But conservatives beware: the combination of polarisation and vetocracy means that future efforts to cut back the government will be mired in gridlock as well. This will be a particular problem with health care. The Affordable Care Act has many problems and will need to be modified. But our politics will offer only two choices: complete repeal or status quo. Moreover, there are huge issues of cost containment that the law doesn’t begin to address. But the likelihood of our system seriously coming to terms with these issues seems minimal.

Some Democrats take comfort in the fact that the country’s demographics will eventually produce electoral majorities for their party. But the system is designed to empower minorities and block majorities, so the current stalemate is likely to persist for many years. Obama has criticised the House Republicans for trying to relitigate the last election. That’s true, but that’s also what our political system was designed to do.

Francis Fukuyama is Senior Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University. His books include ‘The End of History and the Last Man’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments