Ukip isn't the only Eurosceptic party on the rise. But the Union is safe for now

In terms of wielding real power, these parties rarely make headway

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The success of Ukip may be a British story, but it reflects a trend that spans the breadth of Europe. Parties that would dismantle the European project if given half a chance are on the rise all over the continent - not just in those countries suffering 20per cent unemployment rates and stringent bailout terms, but the countries of the North too, where fear of a never-ending future of wealth transfers is driving support for nationalist parties.

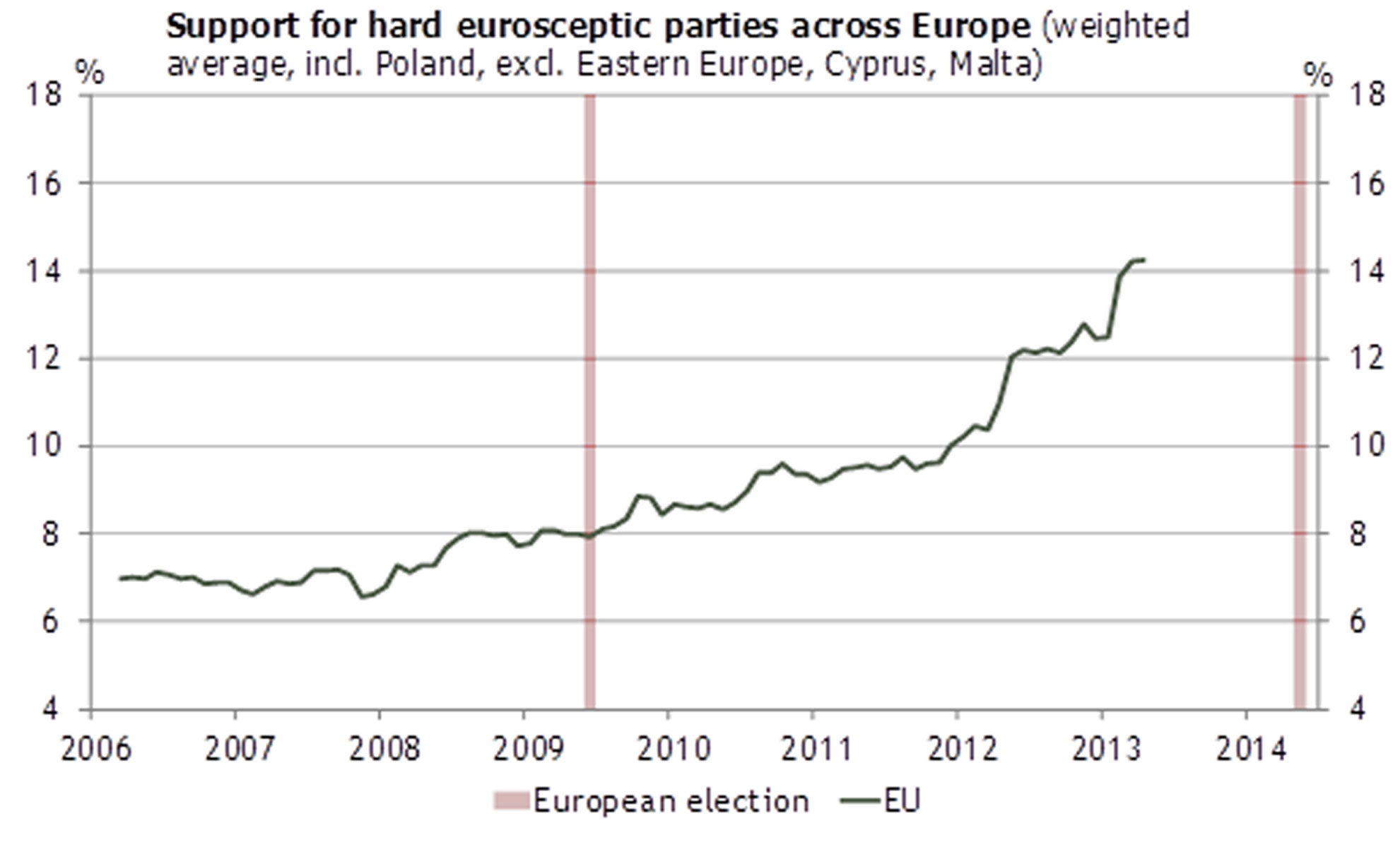

An amalgamation of the various national polls shows that support for Eurosceptics in the EU has nearly doubled since 2009 from 8 per cent to over 14 per cent, reaching up to 30 per cent in Italy, Denmark and Austria.

You don’t have to be a paid-up Europhile to be concerned about this. ‘Eurorealist’ or ‘soft’ Eurosceptic parties like Greece’s Syriza, which merely want radical reform of the EU’s institutions, are not included in the above measure. Those growing most are the hardliners, who view the European project itself as the problem. There is something in that of course – the euro, without fiscal union and political union to accompany it, may well prove to be a congenitally defective project. But if entering the euro was like boarding a malfunctioning rollercoaster, exit would be like wriggling free of the constraints halfway through in favour of hurtling towards a crunchy end 70ft below.

The obvious danger of Eurosceptic parties is that Europe’s prolonged economic malaise boosts their support to the point where they are eventually able to engineer their country’s withdrawal from Europe’s institutions. This won’t happen soon. The chart above shows the marked increase in Eurosceptic support and the steep upward trend it appears still to be following. But in spite of that increase it remains fairly low in relative terms. Support for Eurosceptic parties across Europe is not about to reach the ‘tipping point’ at which their electoral strength presents a direct threat to the future of the eurozone or the EU.

Their real influence lies in their ability to shift the centre of political gravity in their direction. The ability of Britain’s UK Independence Party to win seats in the legislature may be negligible, but that didn’t stop it making the political weather ahead of last week’s local elections. Even a partial repeat of that strong performance at the General Election would come at great cost to the Conservative Party. The threat is ramping up the pressure on the Tory leadership to stiffen their policies on Europe and immigration, whilst Labour ignores the heightened concerns of blue-collar voters at its own peril.

Germany’s new eurosceptic party, Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD), also looks likely to have an outsized impact on German politics this year. In splitting the rightwing vote they reduce the chances of the Free Democratic Party returning to the Bundestag and make a grand coalition between the Social Democratic Party and Christian Democratic Union more likely.

In terms of gaining real power, Eurosceptics have proved themselves pretty hopeless thus far. Italy’s Lega Nord and Austria’s Freedom Party have proved rare exceptions in the recent past, joining coalition governments but in both cases failing to enact much of their agenda and suffering in the polls as a result.

Such parties are ill-suited to the deal-making and horse-trading required to reach government in most European polities. Any concession undermines their key appeal. Voters flocking to such uncompromising firebrands as Italy’s Beppe Grillo would likely recoil in horror were he subsequently to enter the grubby world of coalition negotiations.

The place where the rise in eurosceptic support looks likely to make the most attention-grabbing change is in the European Parliament next year. European elections will take place on the 25th June next year. If current polling trends are any guide, the number of Eurosceptics in parliament could double to a little over 200. This will not, however, be enough to derail European integrationist policies that have a broad base of support amongst the pro-European parties. There are 754 MEPs in the European legislature, and 5 main groupings, with a big majority of MEPs in just two, the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Socialists – the centre-left and centre-right groupings. Both are pro-European (in that they both in principle favour developing the power of European institutions like the Commission and the Parliament). In around two thirds of votes in the European Parliament the two groupings vote together. Their numbers, even after a big injection of Eurosceptic MEPs, are likely to remain overwhelming.

So beyond prompting a bout of wounded soul-searching amongst the European establishment, it is unlikely the new MEPs will be able to disrupt either the day-to-day functioning of the European Parliament, or the Parliament’s relationship with other European institutions like the Council or the Commission.

This is not to say that popular disenchantment with the European project should not be a concern for European policy makers, but they are not facing barbarians at the gate just yet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments