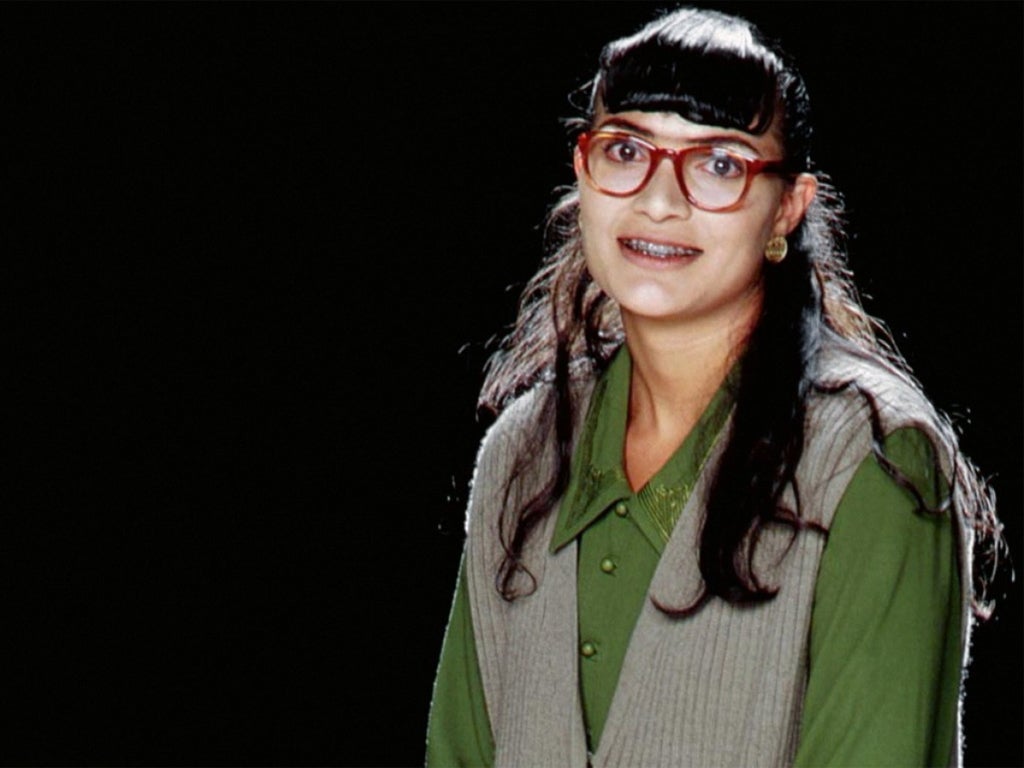

'Ugly girl': The negative messages we send to our daughters

We tell young women that they can achieve anything they want, but the extra pressures are everywhere to be seen.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last week, the Everyday Sexism Project received a deeply moving entry from a fifteen-year-old girl.

It might seem shocking to some, but it was just the latest of many hundreds of similar posts we have received from girls in their teens and younger.

She wrote “I’m fifteen and feel like girls my age are under a lot of pressure…I know I am smart, I know I am kind and funny…everybody around me keeps telling me I can be whatever I want to be. I know all this but I just don’t feel that way.”

She continued: “I always feel like if I don’t look a certain way, if boys don’t think I’m ‘sexy’ or ‘hot’ then I've failed and it doesn't even matter if I am a doctor or writer, I'll still feel like nothing...successful women are only considered a success if they are successful AND hot, and I worry constantly that I won't be. What if my boobs don't grow? What if I don't have the perfect body? What if my hips don't widen and give me a little waist? If none of that happens I feel like [sic] there's no point in doing anything because I'll just be the 'fat ugly girl' regardless of whether I do become a doctor or not.”

Her words reveal a keen perception of double standards in a society that tells young women they can have all the same dreams men can, study at any academic institution they wish and aim for any career path they choose, whilst simultaneously inundating them with an onslaught of daily messages that as women they will be judged almost exclusively on the basis of their looks, regardless of success.

She is even aware of this influence, writing: “I wish the people who had real power and control the images and messages we get fed all day actually thought about what they did for once… I know the girls in adverts are airbrushed. I know beauty is on the inside. But I still feel like I'm not good enough.”

But an awareness of the effect these messages can have is not a strong enough defence against them; not for a vulnerable teenage girl in the throes of peer pressure and puberty, nor even for adult women with a keen awareness of the images and messages that manipulate our self-view. She describes the experience of watching her own mother struggle with the same expectations and insecurities:

“I watch my mum tear herself apart everyday because her boobs are sagging and her skin is wrinkling, she feels like she is ugly even though she is amazing.”

Holli Rubin, a representative of Endangered Bodies, says: “this is a problem of epidemic proportions. Over 60% of adults feel ashamed of how they look…when we put ourselves down in front of our children we are modelling a very negative view. This gets passed down to children who internalize it and consequently begin to feel the same way.”

Within minutes of receiving the teenager’s frank account, messages were pouring in from other women, young and old, testifying to the same feelings of pressure and inadequacy regardless of age or achievement.

“As a 45-year old feminist, I also relate to [her] with my self-judgement via the mirror every day before leaving home.”

“I'm embarrassed that I can still relate to [her] at 39, educated, liberated? Still controlled by image”

“Don't be embarrassed. I'm the same. Guess we owe it to [her] generation to do what we can to change that.”

Hundreds of similar Everyday Sexism entries testify that she is far from alone amongst her peers too. One teenager, who explains that she “chooses to wear modest clothes for religious reasons”, even echoes the same words, choosing the pseudonym “Ugly Girl”:

“I've had people call me hideous, mock me for expressing feelings towards the opposite sex, and outright laugh in my face for believing I could somehow be beautiful and value myself on the inside... Just because I am a women [sic] my image is treated as the only thing that should define me and that should matter. This is the concept of sexism that haunts me in everyday life and I despise it.”

A recent report by the All Party Parliamentary Group on Body Image revealed girls as young as five now worry about their weight and appearance and “one in four seven year old girls have tried to lose weight at least once.” It cited research showing that 13% of girls age 10-17 would avoid even giving an opinion because of insecurities about the way they look.

Last year a teenage girl from my senior school committed suicide after a preoccupation with weight and body image prompted her to develop an eating disorder. At the inquest, the coroner referred to the pressure placed on teenagers by images of “wafer thin girls” in magazines. He stated that the fashion industry was “directly responsible for what happened”.

From the advertising industry and its narrow media ideal of female beauty to the normalised objectification of Page 3; from articles that deconstruct the outfits of female politicians to the programs teaching girls how to nip, tuck, change and disguise their bodies; these messages are everywhere, everyday. The pressure on women and young girls to conform to such stereotypes is overwhelming, and until it is tackled, it will continue to undermine attempts to convince young women like this teenager that she really can “be whatever I want to be”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments