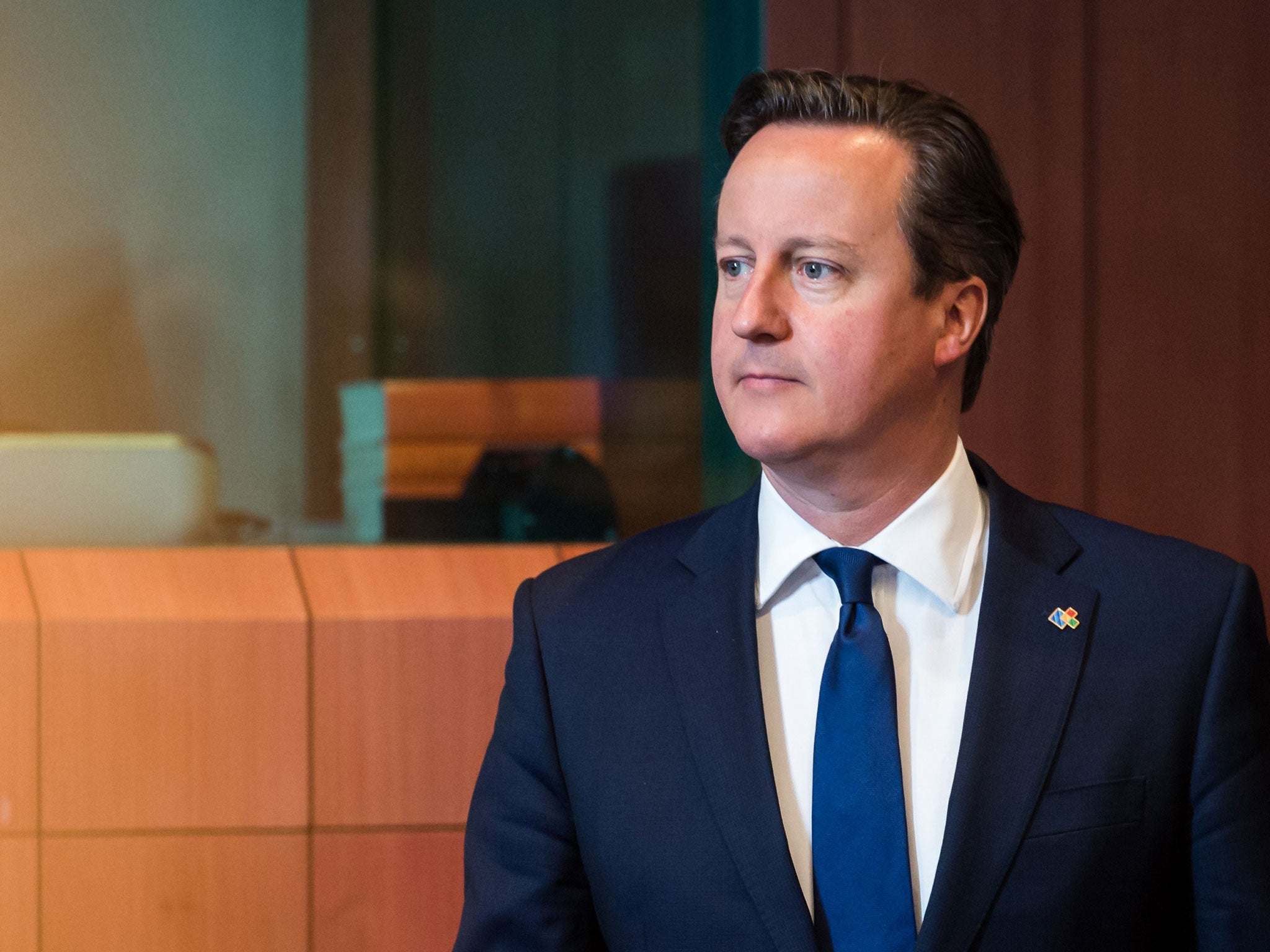

Tunisia attack: With no one left to impress, David Cameron can act freely on terrorism

The degree to which crude political calculations have determined previous responses to terrorism is depressing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.David Cameron is in a rare position as a Prime Minister responding to a terrorist attack. He is liberated from political calculation. He will not fight another election. He no longer has to negotiate with another party in a coalition. He did not lead the UK into a calamitous war and does not need to justify the mistake. He is free to be sensible, if he chooses to be so.

So far the response of successive UK governments and prime ministers to the threat posed by terrorism has been wildly erratic. There is a familiar sequence after an atrocity. First, expressions of horror at what has happened, followed by a parliamentary event where parties broadly come together in their resolute determination.

But normally after this, the mood changes and political calculations assume a disproportionate role. I should stress that these calculations are an unavoidable part of democratic politics. To take the most extreme example, a prime minister would not be human if they did not calculate the political risks of going to war, or chose not to. As UK leaders address the nightmarishly complex terrorist threat, principles mingle with crude calculations. Nonetheless the degree to which crude calculations have determined the UK response is depressing.

Since the September 11 attacks on the US, the UK has fought a war in Iraq that fuelled the terrorist threat, as intelligence agencies warned it would. Tony Blair backed the war partly because he calculated that a UK prime minister, and more specifically a Labour one, could not break its special relationship with the US over a military plan to remove a dictator. It was the calculation of a cautious, expedient leader rather than a crusading evangelical one. Subsequently, as the UK became a target, Blair proposed that suspects could be detained for 90 days without charge. Addressing a private parliamentary Labour Party meeting, he suggested that, in their opposition, the Conservatives “were in the wrong place on this”. He said this with the backing of voters and the Murdoch press. No doubt Blair believed in the proposal too, but political calculations played a part in his misguided advocacy. Rightly, the Commons defeated him over the proposals.

Yet, as a fresh Conservative leader, Cameron was also making calculations about “90 days”. He was not “in the wrong place” as a matter of principle. With eyes on the next election, Cameron opposed Blair’s proposals partly to target the support of Lib Dem voters keen on civil liberties.

The then shadow Home Secretary, David Davis, a genuine and principled opponent of the measure, had several private conversations with Cameron and George Osborne. He could tell they were uneasy opposing Blair, fearing they were indeed in the “wrong place” with the public and Sun editorials screaming support for the measure. Davis resigned soon afterwards as shadow Home Secretary partly because he sensed Cameron’s heart was not in the position he was taking. Once more it was as much a consequence of political calculation as of any other consideration.

Next up was Gordon Brown. As prime minister, he tried to introduce detention without charge, halving it to a still-excessive 45 days. Even his strongest allies were horrified. Ed Miliband cancelled appearing on Question Time because he could not defend it. Again, no doubt Brown saw merit in the proposal. But political calculations were overwhelming as he sought to prove he could deliver for the voters and The Sun and once more put Cameron in the “wrong place”. Predictably, Brown failed to get his proposal through, dropping it as the global financial crisis erupted.

Under the coalition, the dynamics were different but led to the same outcome: proposals to combat terrorism unveiled with a resolute flourish then dropped at Lib Dem opposition. Lib Dems opposed new security measures as a matter of deeply held principle, but in the second half of the parliament, when broadly legitimate proposals to strengthen the online surveillance powers of intelligence agencies appeared, Nick Clegg was keener to show his dissenting distinctiveness. Calculation played its part of the blocking of what became known as the “snoopers’ charter”.

Now Cameron is free to make his moves. In this context, it is easier to specify what he should avoid. He does not have to do something for the sake of it. After the 1998 Omagh bombing, Blair recalled parliament and introduced emergency legislation. It had no practical effect, but Blair felt the need to be seen to be acting, as he did when he suddenly unveiled a “10-point plan” after the July bombings in 2005. None of the points were implemented.

Nor does Cameron have to waste political energy out-manoeuvring his opponents. Labour and Lib Dems are currently on their knees. He has no need to impress voters and the media as Brown did. Unlike Brown, Cameron has won an overall majority.

Political calculation has played an excessive role in the past partly because leaders felt the need to do something in the face of horror. when in reality for the UK the hard grind of unseen vigilant intelligence is the key. Elected leaders have an important but limited role.

But perhaps Cameron will feel freer than his predecessors to guide us in a more measured way as to the scale of the threat in relation to the UK. Was the killer, a so-called lone wolf, more intent on wrecking Tunisia’s economy than attacking the UK, or both? Is Isis focused largely on a regional power struggle? Home-grown terrorism is evidently a big and dangerous threat, so how best to combat it? How to form effective coalitions with Muslim communities while challenging them? Cameron’s freedom to make right judgements does not necessarily guarantee he will do so, or make his task less daunting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments