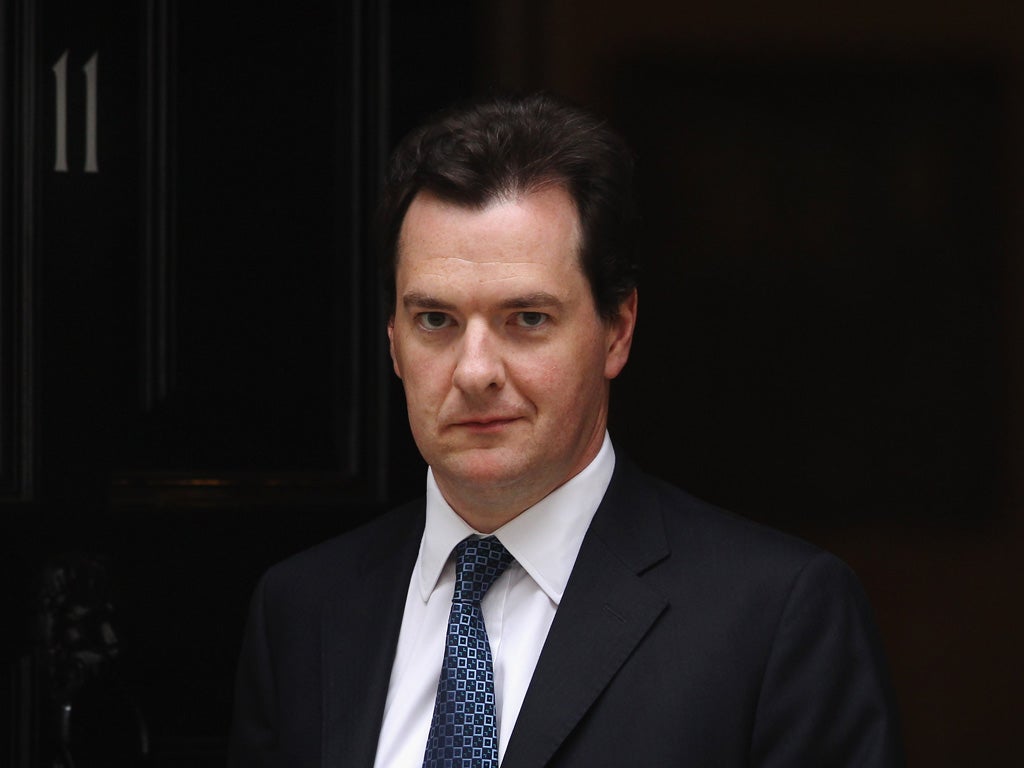

Trapped by his own ideology, the Chancellor is lonelier than ever

Cabinet ministers are becoming more assertive, behind the scenes and publicly

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I wonder whether George Osborne is as self-confident as he appears to be.

The Chancellor’s robust projection of a precarious case gives the impression of almost provocative arrogance. Perhaps the public façade is a true reflection of his unyielding commitment to his economic policies, but I doubt it. Osborne is human and must occasionally suffer from bouts of agonised introspection about his chosen course. How could he avoid such private agonies when in yesterday’s Budget he announced that the growth forecast was halved, the debt target was missed, and borrowing was only slightly down due to an unexpected underspend by Whitehall?

The degree to which last year’s calamitous Budget shaped the one he delivered yesterday shows that Osborne is not as confident as he seems. In a way that was almost painfully transparent, the Chancellor sought to redress the errors he made then, like a wayward pupil who had learnt the art of arduous revision. Twelve months ago, he was accused of being out of touch as he put up taxes on Cornish pasties. Now he gets a headline by cutting the tax on beer and petrol. In order to counter the still toxic effect of the income tax cut for high earners announced last year, Osborne said that low earners would cease to pay income tax earlier than planned.

Elsewhere, there were a few striking measures aimed at boosting home ownership, and there was help for small businesses. Michael Heseltine, the Tories’ genuine moderniser, appears to have influenced parts of the Budget with his innovative proposals for growth. It is to Osborne’s credit that he is willing to take some of these ideas on board.

In spite of the obvious effort to learn the painful lessons from 12 months ago, a single pivotal sentence links the two Budgets. In both, Osborne declared his attachment to fiscal neutrality. The tax cuts announced yesterday will have to be paid partly by more spending cuts. The phrase “this Budget will be fiscally neutral” is nearly always deadly because it means that although a Chancellor feels compelled to unveil lots of new policies, he has no intention of spending any more money overall.

The phrase virtually destroyed Gordon Brown when he uttered it in his last Budget as Chancellor. Brown announced a cut in the basic rate of tax that was paid for by hitting low earners. Osborne went in search of taxes on pasties last year because he needed the money to make ends meet. This time, he targets further public spending cuts on top of those already being planned.

Vaguely expressed spending cuts are much less politically explosive than the specific tax rises of a year ago, but in a few months’ time, explosions loom again with the public spending round that begins formally in June. That now becomes even tougher than it already was. Yesterday’s Budget statement – so much more professionally drafted than last year, painstakingly scrutinised in advance for any potential “omnishambles”-type embarrassments, and the beneficiary of great advance political discipline with no partisan leaking from senior Liberal Democrats – is not the main economic event of the year. The spending review will be, partly because of the political context in which it takes place.

Cabinet ministers are becoming more assertive, behind the scenes and in public. Their hyperactivity has partly fuelled speculation about leadership bids. Such speculation misses the point. There may or may not be a leadership challenge. What is certain is that ministers sense there is fresh political space for them to make a case, partly on behalf of their departments. Will Vince Cable, Theresa May, Philip Hammond, Iain Duncan Smith and others rush to deliver cuts as they did in the autumn of 2010, when the authority of Osborne was at its height? Will they do so as they struggle now to implement the cuts they agreed to then? These are the big questions that arise from a Budget that is dependent on all these suddenly bigger ministerial beasts being willing to make more sweeping spending cuts.

Osborne’s lack of confidence is not only highlighted by the way in which he responded to the fallout from last year’s Budget. It is almost ideological. He has little faith in the ability of the state to deliver growth, and so turns for help – with even greater intensity – to the Bank of England. Evidently Osborne regards his appointment of Mark Carney to succeed Sir Mervyn King as Governor as a coup of immense importance. Part of his message yesterday was, in effect: “Over to you, Mark.”

With a neat symbolism, Osborne started to lose his voice as he explained in some detail how he was giving the new Governor greater flexibility in meeting his inflation target. The supposedly mighty Chancellor also added that “unconventional monetary policy” would play its part, presumably in the form of more quantitative easing. It was as if Osborne was choosing to lose his public voice and hand it over to the saviour from Canada, untainted by political storms whirling around the Treasury.

The only alternative to this act of political self-effacement was to drop Plan A, a course that has become economically desirable but politically impossible. Osborne chose to trap himself at the beginning of his reign and there is no escape. More quickly than I thought possible given the fashionable consensus in support of his early moves, Osborne is becoming isolated.

Some Conservative MPs are calling for tax cuts, and privately describe Osborne’s phrase that there will be “no unfunded tax cuts” as economic illiteracy. Vince Cable wonders aloud whether the “balance of risk” has changed in favour of more borrowing for capital spending. Nick Clegg admits that the Coalition made an early error by cutting capital spending.

Suddenly, the shadow Chancellor, Ed Balls, is no longer the voice in the wilderness as he was when he warned about the calamitous consequences of Osborne’s fiscal conservatism in the summer of 2010. It is the Chancellor who is politically lonely now, clinging desperately to a narrative about “staying the course” that, come election time, he hopes will resonate.

His isolation will deepen when he turns to his cabinet colleagues and demands more spending cuts in June. The summer becomes even more a season of fragility for both Osborne and the Prime Minister.

s.richards@independent.co.uk Twitter: @steverichards14

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments