Time to change the definition of charity

Tax relief should only be offered for donations that alleviate poverty and suffering

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Questions of what exactly makes up a “charity” have vexed politicians over the ages. Typically, the source of the irritation has something to do with tax, and the trouble goes back to 1601, when the government of Queen Elizabeth laid out the Charitable Uses Act. This legislation – pioneering at the time – defined charity in the broadest of terms: anything from the “advancement of religion”, to “other purposes benefiting the community”. And the church has not got any narrower in the four centuries since. To use the most divisive example, private schools still qualify as charities, as does the English National Opera – hardly organisations attuned to the needier elements of British society.

This presents a problem for Treasury ministers, in so far as every donation to charity, whether its purpose is to soothe the last days of a donkey or lift a child out of poverty, attracts the same amount of tax relief. Any government – even this one – will view helping poor children as more of a priority than the fate of beleaguered farmyard animals. But, as things stand, it cannot promote one form of donation over the other, without changing the definition of charity altogether. Someone paying the top rate of income tax will effectively be gifted 40p by the state for every pound they give, be it to bring a Russian mezzo-soprano to the UK or clothe a Syrian refugee through winter in Za’atari camp.

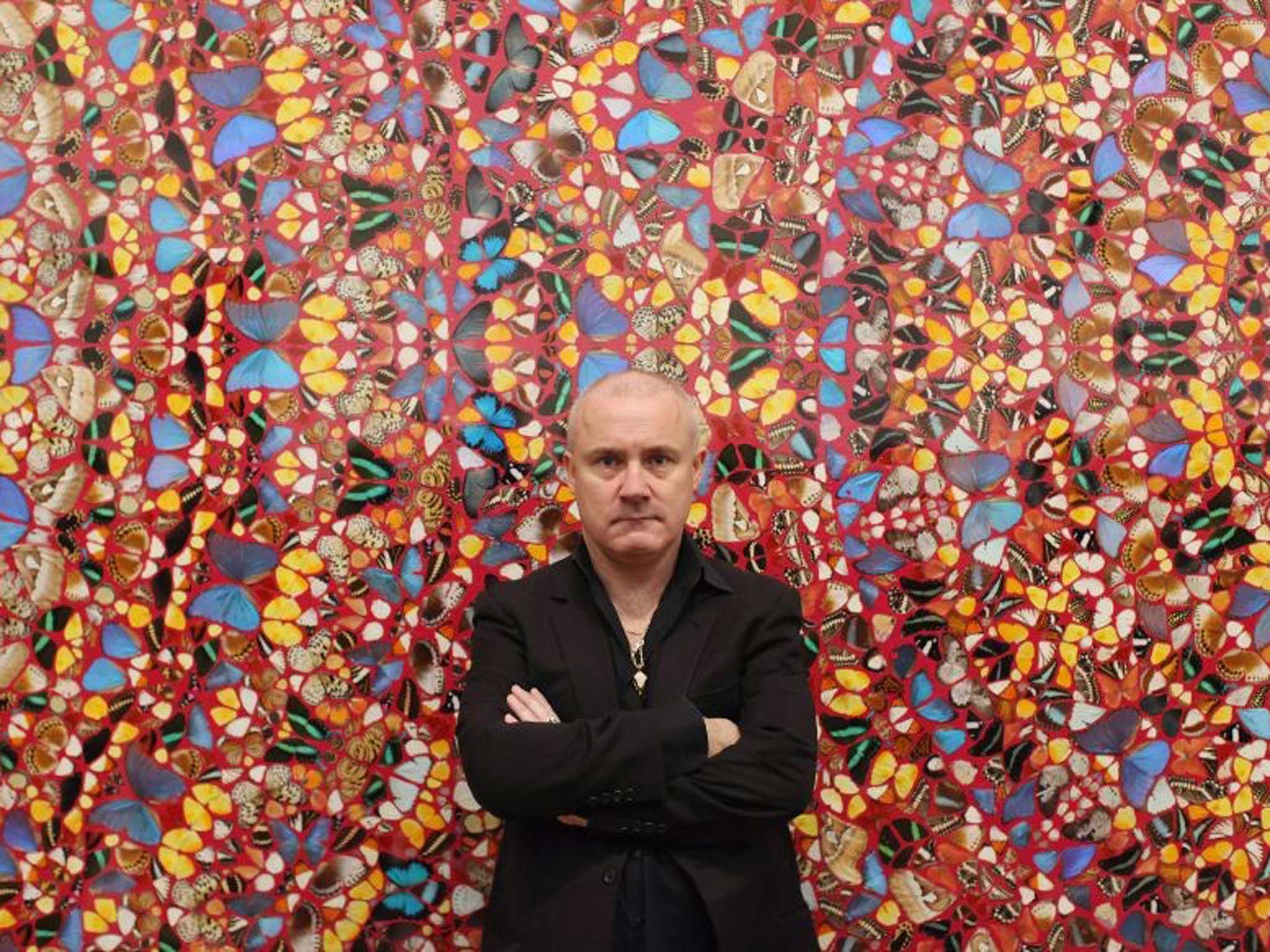

I was reminded of this running bugbear by the publication of the Sunday Times Giving List this weekend. It goes without saying that everyone on the list, from Damian Hirst through the founder of Bet 365 to Lord Sainsbury, deserves praise – and ungrudging praise – for deciding to give money away at all. Many of their peers on the Sunday Times Rich List, the showier elder brother of this weekend’s list, sit on their income, proverbial dragons in Kensington dens.

And yet, from the perspective of the guardians of state finances (or at least those who share my qualms), the list of what causes benefit from the largesse of millionaires invites question. The main beneficiaries of a large number of the top 25 on the list include “educational” organisations – which means university endowments, as much as helping a child on free school meals get a place. Many also give to the arts. Though implicit in other categories, “poverty relief” is mentioned just once. Of course, everyone has the right to give wheresoever they like. The question is whether the state should reward all donations with equal tax relief.

Last year the Government granted £1.2bn in such relief for individual donors. Among a cornucopia of pain for public services, the Conservatives now plan to cut social care by a further £1bn, leaving the elderly and young children in deprivation that charities struggle to mop up. I would rather the state kept that £1.2bn, and put it to good use. The rewards of a good conscience (and a gala feting or two) ought to be enough for a rich donor, especially since it is by no means clear that reducing tax incentives would cripple the charitable sector, as some claim.

A more nuanced, but perhaps more workable solution, would be to weight tax relief towards charities that work to alleviate poverty and suffering. The government tried something similar in the 19th century, defining charity as more strictly tied with alms-giving, but the move was overturned in the courts. So we remain in this situation: where the poor pay more tax to make up for the charitable tax breaks enjoyed most by the rich. I enjoy good theatre as much as the next person, but the curtain should be drawn on a tax system that treats a production of Twelfth Night the same as a food bank.

The “food of love” might be music, but the food of the hungry is - and will remain - food.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments