This Week's Big Questions: Is progress a myth? Is al-Qa'ida's threat disappearing? What is the place of royalty in modern society?

This week's questions are answered by political philosopher and author, John Gray

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Your new book is subtitled “On Progress and Other Modern Myths”. Why is progress a myth?

Progress means cumulative, near-irreversible advance of any kind, and in science and technology it’s a fact. But the increase of knowledge – which is the source of scientific and technological progress – doesn’t make human beings any more reasonable, and gains in civilised society are very easily lost. Great advances in ethics and politics – religious toleration and the partial emancipation of women and gays, for example – aren’t like advances in science, which are rarely reversed.

A vital advance such as the prohibition of torture can be lost in the blink of an eye. When almost exactly 10 years ago I published a spoof called “Torture: a modest proposal” in the New Statesman, suggesting that torture should be used as part of the global struggle for democracy and human rights, many of those who recognised my satirical intent regarded the piece as a perverse exercise in pessimism. Less than a year later, the photographs coming out of Abu Ghraib showed torture being used as a result of directives that were later proved to come from senior operatives from the world’s pre-eminent liberal democracy.

You speak about humans hiding behind language. Isn’t language humanity’s greatest achievement?

Humanity’s greatest achievements are often very mixed in their effects, and language is no different. The trouble with language is that people treat its creations as if they were real things. If millions died in the name of God, just as many have been killed for the sake of “humanity” – both of them dangerous abstractions. The crimes both of traditional religions and of the secular creeds of modern times come in part from worshipping words. True scepticism begins and ends with a certain mistrust of language, and tends to be found among poets and mystics more than philosophers.

As someone who has studied resource scarcity, what’s the best way to ensure that humankind’s future energy supplies are met?

There is no single solution for humanity’s energy needs – we will have to use many different technologies. I think both solar/wave/wind and nuclear energy will be needed but here I’m in a small minority, since the debate has become highly polarised. There is no easy way ahead. The best we can hope for is to muddle through without causing too much more irreparable damage to the planet.

Is there any point in a prime minister expressing remorse over events that happened decades before he was born?

Whether or not a prime minister was born at the time of the event for which he or she apologises is not very important. What matters is whether the apology does any good in the present and future. I’m not a great fan of David Cameron, but his apology for Bloody Sunday certainly helped to solidify what will probably continue to be a rather uneasy peace in Northern Ireland. His expression of regret for the Amritsar massacre was less effective, since it stopped short of a full apology for an atrocity that Churchill, Asquith and others condemned outright at the time.

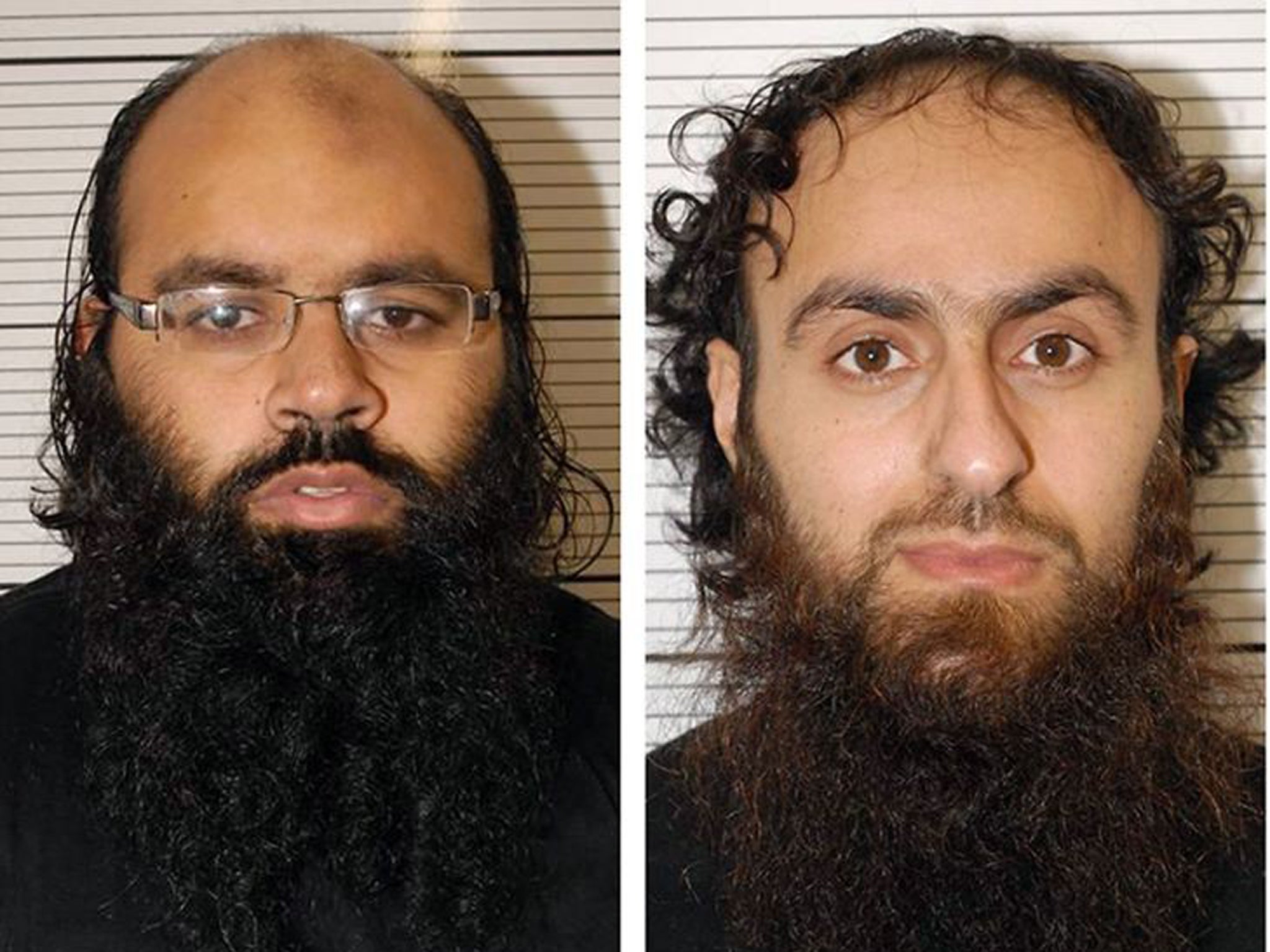

You’ve also written about al-Qa’ida. Is its threat, as one newspaper implied recently, disappearing?

Today, al-Qa’ida isn’t just an idea – as is sometimes claimed – but nor does it operate as the cohesive organisation it may once have been. Rather like late 19th-century anarchism, it seems to be a continuously mutating network of groups with similar goals and strategies. There are two large differences, however: unlike 19th-century anarchism, which never gained mass support, al-Qa’ida has been able to command mass sympathy in some periods of its history; and unlike the anarchists, who mainly targeted state officials, al-Qa’ida has always been ready to attack civilian populations. For these reasons among others, al-Qa’ida can’t be written off. The danger at present is that Western intervention in Libya and Syria may actually be strengthening al‑Qa’ida-affiliated groups.

What does this week’s episode involving Hilary Mantel and the Duchess of Cambridge tell us about royalty’s place in modern society?

The British monarchy is a postmodern soap opera masquerading as an ancient institution, but I much prefer it to any of the alternatives. Monarchy of the sort we have in Britain has an enormous advantage over blood-and-soil nationalism, while becoming a republic would inevitably mean defining citizenship in terms of some highly disputable principles. More practically, what is so attractive about the idea of a buffoon like Blair becoming head of state? I prefer to make do with the results of the genetic lottery.

Who is most at fault in the horse-meat scandal?

More than any organisation, it’s the demand for cheap meat and the vast global supply chains that supply the meat that are at fault. The scandal exposes one of the fragilities of globalisation. Worldwide markets and de-regulation are a toxic mix of which the meat scandal is only the most recent example.

Is austerity the way to restore health to the economy?

I share the view of George Soros, whose view of how economies actually work is rather more credible than that of George Osborne: the economy can’t grow and contract at the same time. I’m not a doctrinaire Keynesian – the policies Keynes advocated in the Thirties and that were applied successfully after the Second World War won’t necessarily work well today. But it remains the case that cutting the public sector in a time of recession is no way to restore health to the economy.

John Gray’s latest book is ‘The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths’, published next week by Allen Lane

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments