There's no sense in querying the Mark Duggan jury

To accuse them of being illogical or stupid is to reject what a jury is for

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

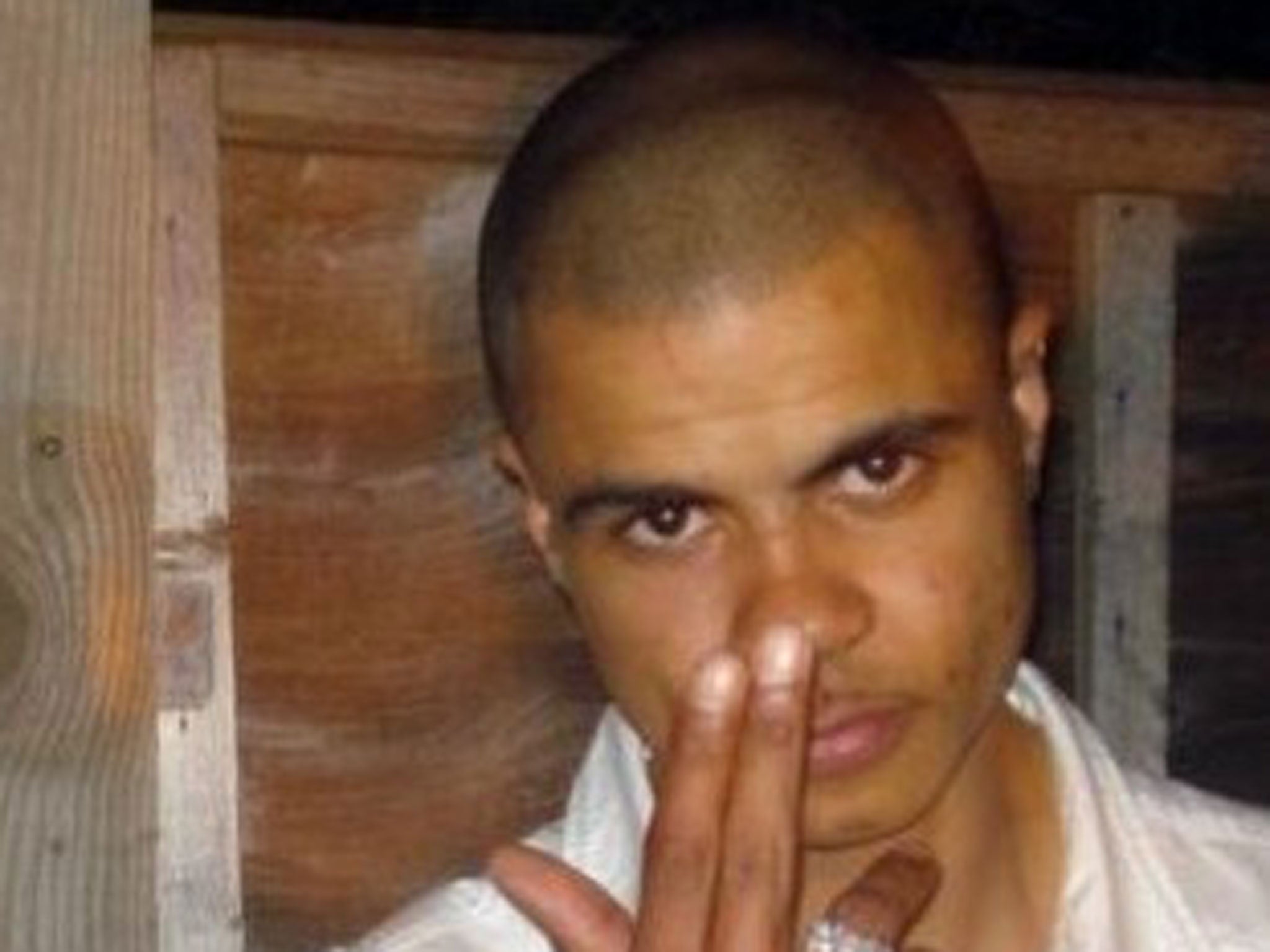

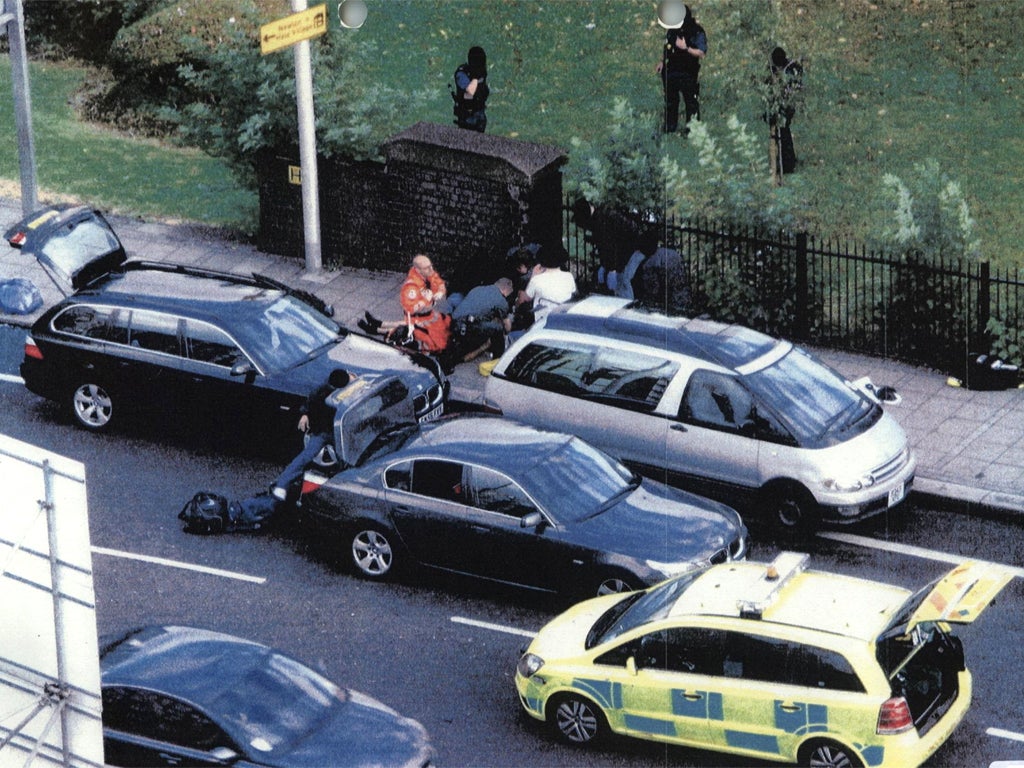

Your support makes all the difference.Whatever happened to the late Mark Duggan’s Aunt Carole the night after a jury decided that her nephew had been lawfully killed, she was certainly singing a softer tune by the morning. Having stood with other members of the Duggan clan outside the law courts on Wednesday evening, raging about “execution” amid chants of that easy slogan, “no justice, no peace”, yesterday it was all about keeping calm and the family pursuing its challenge by judicial means.

And thank goodness for that. With any luck, this means there will be no repetition of the riots that engulfed Tottenham and elsewhere two summers ago in response to Duggan’s death. But the apparent pacification of Aunt Carole will not stop the questions, nor should it.

The conduct of the police both before the fatal shooting (why and how they mounted their operation), and afterwards (when the officers involved were allowed to confer on their statements), leaves a bad taste and invites suspicion. And yet again the inadequacy of the Independent Police Complaints Commission has been exposed. Can we please have it replaced? Now.

That specific aspects of the affair relating to police behaviour raise questions, however, does not, of itself, discredit the verdict. To my mind, the most pernicious response here came less from members of Duggan’s family and their supporters – whose emotional excesses can just about be indulged, at a time when they had apparently expected something different – but from a narrow swathe of MPs, lawyers and criminologists. These professionals did not, of course, resort to terms such as “scum” to describe the jurors – perish the thought. But they did something almost as damaging. They cast doubt on the jury’s reasoning abilities, with all the understatement and condescension that is so characteristic of certain sections of their class.

In particular, they professed themselves “baffled” that the jury could at once find (by a margin of eight to two) that Duggan was not armed when he was shot, and, by the same margin, that the police had acted lawfully. They also drew attention to a discrepancy in the voting. While these verdicts went eight to two, the jurors decided by nine to one that Duggan had thrown the gun 6m on to the verge, (rather than it having been thrown, or planted there, by the police).

Are the jury’s votes really so inconsistent as to render them invalid? To a highly trained legalistic mind – or someone used to being on the wrong side of the police – there might well seem to be a contradiction between Duggan being unarmed when he was shot and being “lawfully killed”. The headline here is that the police shot dead an unarmed man.

But this is to look at what was occurring from just one perspective. If, instead, you see what happened as the police officer says he saw it – a man believed to have picked up a gun and to be preparing to fire it – you could well regard the action as lawful. The suspect might have been unarmed at that moment, but there was good reason for the police to think otherwise. And this is presumably how the jury regarded it, by a majority of eight to two.

There are occasions, and the Duggan inquest is one of them, when you would like British jurors to be able to explain what went on in the jury room, as their US counterparts may – though in this case it is probably better, for their own safety, that this is not allowed. But to accuse them of being illogical or – in essence – stupid is to reject what a jury is for. Selected randomly from the electoral register, they are the voice of ordinary people, the “community” in the proper sense of the word.

Their judgment might sometimes appear “perverse” – another word that cropped up this week – to the experts, but “expert” opinion may sometimes seem “perverse” to the rest of us when it seems to uphold the letter rather than the spirit of the law. In the Duggan case, the jurors applied their common sense to the sum of the evidence and came down by a big majority on the side of the police.

It could have been different. Given the passions aroused, this could have been a hung jury, but it wasn’t. Not by any manner of means. Those 10 individuals produced a verdict which to me – after listening to many phone-ins and reading many comments over the past 24 hours – seems to have a similar majority of the public on its side.

In the wake of the verdict, there has been much talk of policing by consent, as though local anger should sway the law. But there cannot be one law for Tottenham and another for the rest. Those jurors were listening and judging in the name of all of us. They gave our consent by a large majority. They probably got it about right.

A Europe without Merkel?

For perhaps the world’s two best-known Germans to suffer ski-ing accidents within a couple of weeks of each other has brought a deluge of comments about the dangers, or not, of this winter pursuit.

Understandably, the German Chancellor’s office was keen to play down the seriousness of Angela Merkel’s injury. It made clear she was skiing cross-country, not downhill; that she did not cut short her holiday, and only learned of the fracture after consulting a doctor once home. Her travel and meetings may be curtailed for a few weeks, but she’ll be working as assiduously as ever, but from home.

So that’s all right, and I’m sure that it is. But I wouldn’t mind betting that when news of her injury first broke, however minor and temporary it might be, scenario-planners the world over were suddenly thinking the hitherto unthinkable and considering the implications of a Germany and a Europe post-Merkel. The Chancellor, just starting her third term after a thoroughly convincing election victory, has come increasingly to be seen as a fixture – reliable, responsible, reassuring. You tend to take it for granted that she will be there forever, with her sensible clothes and sensible views. Not just Germany’s Mutti, but ours, too.

It is often and wisely said no one is indispensable. Which may be true. But until last weekend, Angela Merkel looked perilously close to becoming the exception that proves the rule.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments