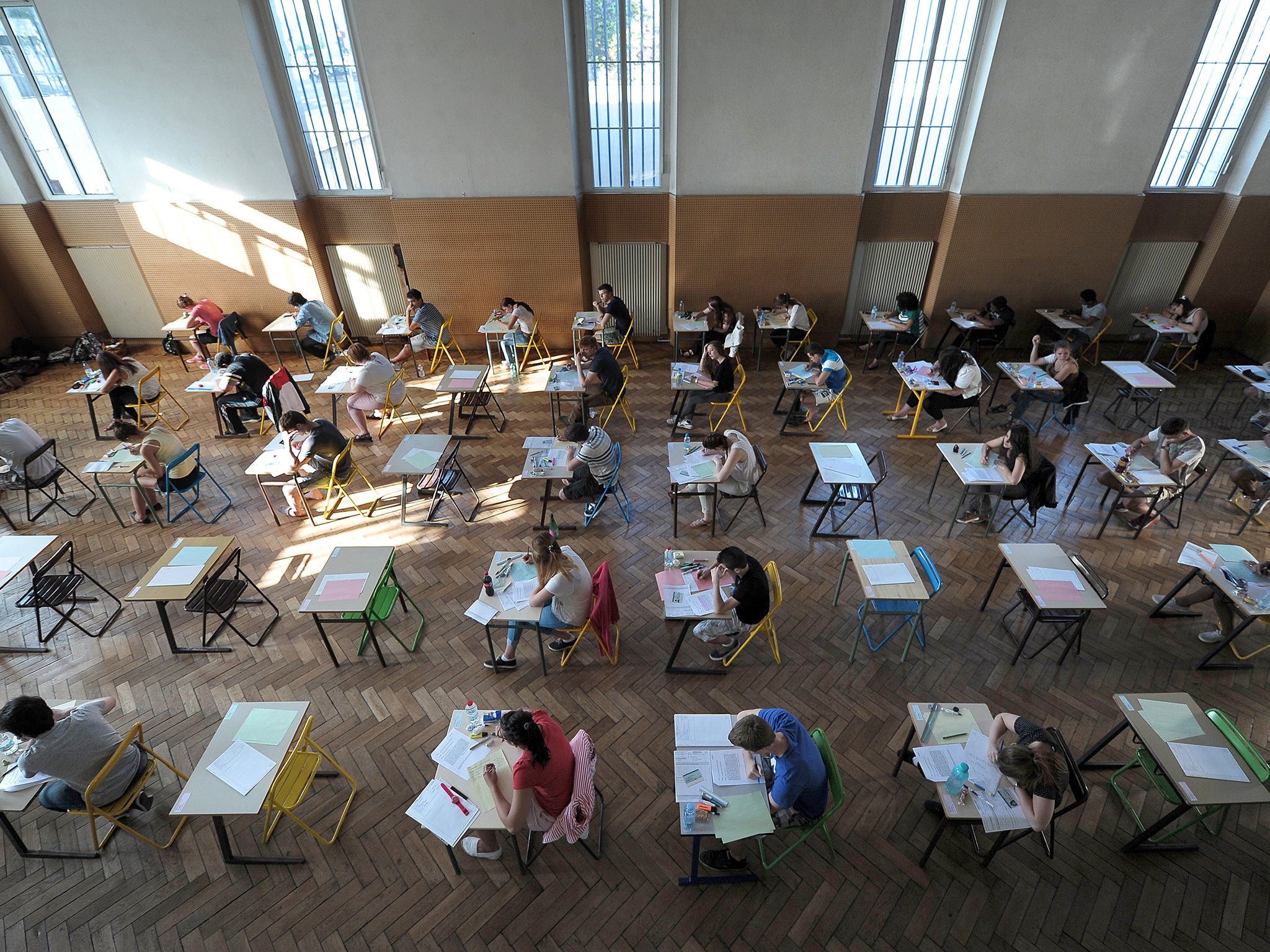

The young will never learn if they're allowed to use Google in exams

I'm all for teaching students how to use the search engine, but getting them to rely on it will only hinder their progress later on in life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It took me back to read that Mark Dawe, the OCR exam board chief executive, is pushing for pupils to be allowed access to Google in GCSE and A-level exams.

Where was Dawe when we stayed up all night before our law exams at university? I lost count of how many caffeine tablets I consumed trying to memorise constitutional law and Roman law for the following day.

In the morning, in constitutional, I pulled a blinder. My brain was racing, literally, and I sailed through questions about public bodies over-reaching themselves. But oh dear, no sooner did I look at the Roman paper in the afternoon, than I hit the wall: my mind went blank.

I was exhausted. Try as I might, I could not summon the mental wherewithal to discuss the legal consequences of Tiberius’s slave crashing a chariot into a vegetable stall. I sat there, a wreck of a person. What I’d have given then to have had access to a Roman law textbook.

In some respects – as an alternative to learning by rote, inventing crazy acronyms and rhymes, trying to memorise a page as a picture – having Google to hand makes a lot of sense. I would certainly have been able to construct a semblance of an essay in Roman law.

Ah yes, but would I still have known and understood Roman law itself? Contemplating Dawe’s call, and it’s not new – various education academics have made the same plea (how do I know? Googled it, of course) – I realise that Google can make you an immediate expert in anything.

But you’re not really expert – Google will only take you so far, supplying a coating of veneer. Anything deeper, beyond that, has to be worked upon and must be won.

The Dawe theory is that exams do not equip pupils for the modern world, a world in which if they want to know anything, they merely have to type the name of the subject and press return.

To an extent, that is true. But it’s also a world that assumes detailed memory plays no part, in which someone can only function with a search engine or calculator at their side. In adult life, are people not often expected to be able to hold a conversation, to make a pitch, to do a simple calculation, without reaching for the omnipotent search facility from California?

According to Dawe, the idea of introducing Google to examinations is comparable to the ages-old debate of whether books should be allowed during tests. I disagree – Google is faster, all encompassing, and comes attached to another piece of weaponry: cut and paste.

By all means equip children to master Google. That’s what should be tested – speed and accuracy of using the search engine. Set puzzles that require someone to display handling of Google, to narrow a search right down to the essential components. Ensure they can distinguish between references that are authoritative and reliable, and those that aren’t. Teach Google. That’s a capability that will stand someone in good stead, along with recall, research, logic, problem-solving, and all the other accoutrements of being equipped for life.

As it was, I scored a first in constitutional and what my tutor described as “the lowest third in the university” in Roman law – 13 per cent. But the Roman law experience hardened my growing detachment from law. I was going off it, rapidly. Imagine if I had been able to search Google. I might have gone on to become a lawyer – one that thanks to the ever-present Google only ever went through the motions.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments