The next election’s fiscal mood music could be very different

Will Robert Chote’s OBR forecast away the £33bn hole in the public finances?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Boom times are back!

Or so scream newspaper headlines as evidence mounts that the economy is picking up speed. Given the gloomy prognostications for growth just a few short months ago, the size of the apparent bounce is striking. What happens next is going to have big implications for politics and the public finances.

For almost three years, news about the state of the economy has been like listening to a particularly dreary dirge. Back at the emergency budget of June 2010, the chancellor set out unprecedented cuts that, it was thought, would fix the public finances over four years. By 2013, it was forecast, the economy would be growing at a good clip of 2.9 per cent.

But in its latest offering, back in March, the Government’s independent forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), predicted growth of just 0.6 per cent for this year. That deterioration in the outlook, and the associated rethink about the damage wrought by the crash, had a huge impact on the watchdog’s assessment of the economy’s potential. And a smaller economy generates less tax revenue.

Since the OBR, led by Robert Chote, is also responsible for telling the chancellor whether his fiscal plans are sufficient to eliminate the budget deficit, those revisions had dire implications for the scale of cuts — or tax rises — the Chancellor needed to balance the books. That’s why George Osborne has pencilled in a further £33bn of cuts to public spending after 2015, some of which we heard about in the recent spending round.

Even by 2015, some government departments will be a quarter smaller than they were in 2010. So with health, schools, and pensioners all protected from further cuts, it’s hard to see how the extra savings can be made without decimating other public services and imposing some draconian working age welfare cuts.

But just as we were getting used to this gloomy timbre, somebody seems to have switch the record for a vigorous allegro vivace. There’s no denying that the economy is stirring from its two and a half year torpor. It grew by a respectable rate in the second quarter of the year, and subsequent data suggest that the third quarter could be impressive. Business activity jumped last month to suggest levels of expansion not seen since the 1990s. Retail sales growth is stronger than it has been for years. And, frighteningly, the government’s madcap housing policies seem to have succeeded in whipping up a fever in the housing market.

If the economic momentum builds into the autumn, all eyes will be on the OBR once again. Will they start tapping their feet to the up-beat tempo? Given recent data, it wouldn’t be surprising if growth this year ended up above 2 per cent. Quite apart from demonstrating just how much of a thankless task forecasting GDP growth is, that would be quite a turn around.

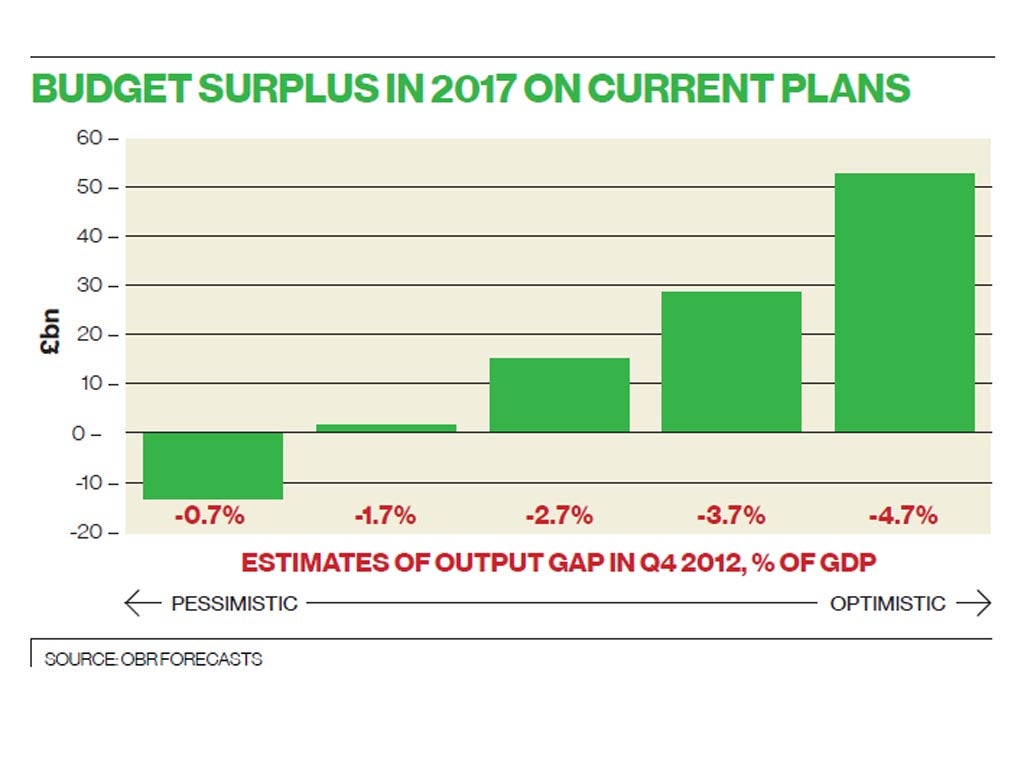

A bounce-back on that scale could send the OBR — and other forecasters — back to the drawing board. Among independent forecasters, views on the economy’s potential range widely. But if the bounce were to put the OBR in the camp of those who have until now been thought of as optimists, the impact on the public finances would be huge. As the chart above shows, based on a range of OBR projections, if you think the economy is currently running well below its potential, that implies the public finances will be in a healthy surplus by 2017 on current plans. Conversely, if you are even more pessimistic than the OBR’s March central assessment of a 2.7 per cent output gap, there will still be a deficit in four years’ time.

If estimates of the economy’s future potential were revised up by, say, two per cent, the £33bn hole in the government’s finances could all but disappear. It’s far too early to say whether such a large revision is likely. But as Jonathan Portes of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research has pointed out, looking at the early 1990s recession, it wouldn’t be the first time that respected commentators have ended up being way too pessimistic about the economy’s potential after a recession.

The political implications of this would be huge. The 2015 election would cease to be the shroud-waving spectacle it currently promises to be. Rather than competing to offer to least unpopular spending cuts and tax rises, politicians could get back to the much preferable task of arguing over how to spend the windfall or whether to give it back in tax cuts. Would a recovery prove that the Government was right all along with its policy of austerity? Whether the economy would have taken off much sooner had the deficit cutting programme been postponed, avoiding huge economic damage, nobody knows.

Whether a sustainable bounce indicates that, backed by loose monetary policy, the economy was well capable of handling the cuts all along, nobody knows. Whatever the truth, for the Coalition a sustained economic turn-around would clearly be a powerful electoral asset.

So the prize is huge, but the big question is whether this nascent recovery is sustainable. Is this a brief respite before requiem resumes? Or the prelude to a triumphant crescendo? Sadly there are grounds for concern. A consumer-led recovery is all well and good, but with wage growth languishing well below inflation, shoppers are having to draw down their savings and put the bills on the credit card. Sound familiar?

The result is that the household savings levels have fallen back to where they were in the middle of the last decade. A consumer-led, debt-financed recovery doesn’t look much like the “march of the makers” that the Chancellor promised us.

The key to sustained growth is strengthening corporate investment. But that will only happen if companies think there are some customers out there, either here or abroad, to buy the resulting widgets. That in turn means that there will need to be a pick-up in wage growth to support the shoppers who are running out of economic puff, or a decent recovery in the eurozone to boost exports. Both look doubtful, even with the current ultra-loose monetary policy.

If there’s one thing we can take away from the bounce that nobody saw coming, it’s that nobody knows how the next movement goes. But either way, the next few months will have a profound impact on British politics.

Ian Mulheirn is outgoing director of the Social Market Foundation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments