The House I Live In shows how America's drug war has failed. Now, Obama must do something about it

Mandatory minimum custodial sentences and a ludicrous disparity in sentencing for crack and cocaine use must be addressed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The balloons have deflated, the hangovers been cured, the jubilation from Obama’s big night dissipated. Now it’s time to get back to business. The President must use his revived political confidence to address a problem that has haunted America for decades: the highly destructive policies of the War on Drugs.

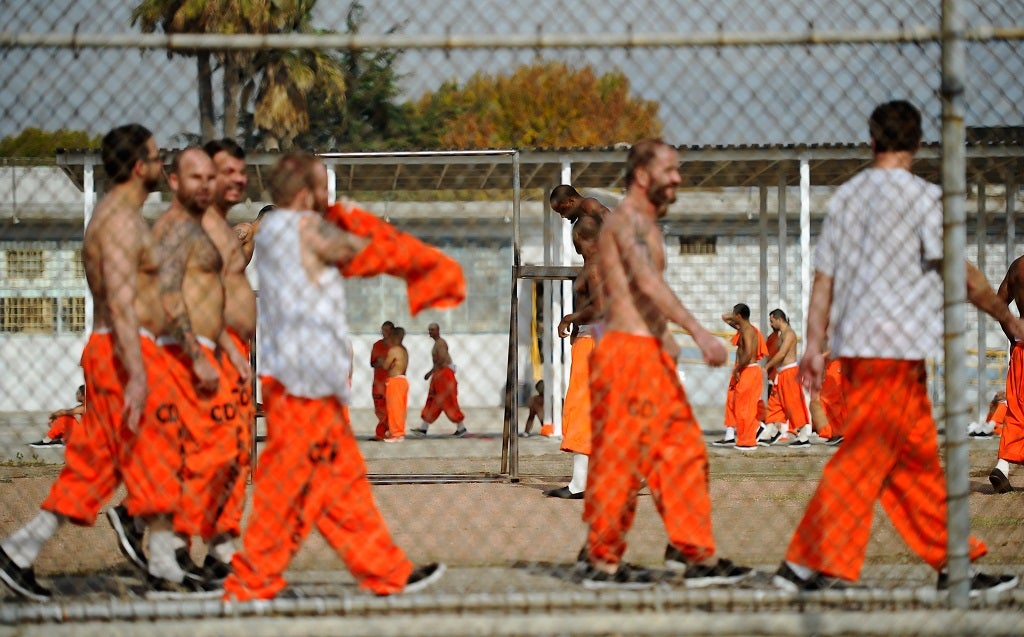

Eugene Jarecki’s new documentary The House I Live In, which I worked on as Production Intern, powerfully illustrates the impact of the government's illegal drug policy on Americans and the sheer absurdity of the situation in prisons: between 1980 and 2000, the number of people behind bars for nonviolent drug law offenses increased from 50,000 to nearly 500,000 – but a victory against drugs moved no closer.

The start of America's drug law madness can be seen in 1986, when the Anti-Drug Abuse Act was signed into law by Ronald Reagan. That year, there was scare-mongering talk of a crack epidemic in America's cities (Reagan himself called it a ‘plague’). Politicians of all stripes wanted to be seen to be tough on crime and ready to do anything get these threatening, violent crackheads off the street, into prisons. So the Anti-Drug Abuse Act was drawn up - with zero expert consultation.

It introduced mandatory minimum sentences for all drug offences, whether violent or not, and set a sentencing ratio of 100:1 for crack and powder cocaine. This meant that a person found with 5 grams of crack cocaine was treated the same as someone with 500 grams of powder cocaine - and both would be given a mandatory minimum sentence of five years. What’s the difference between the two? Crack cocaine is simply powder cocaine, baked in an oven with water and baking soda.

But powder was seen as the “professionals’ drug”. Crack was viewed as more dangerous, the substance of criminality - because it is a cheaper and more efficient way of ingesting cocaine for highly addicted users.

It was also understood to be the ‘black drug’, in the same way that we view crystal meth as the white drug of the Midwest. But African Americans do not use crack cocaine any more than whites — in fact, whites use it more. Black people make up 13% of the population, and about 13% of crack users. Yet 90% of the crack defendants in the federal system are black.

Mandatory minimums are a major cause of America's drugs catastrophe. They obligate the presiding judge to give a ‘one-size-fits-all’ sentence, even if the crime is a nonviolent one. These have had the effect of hugely inflating the prison population, and further undermine justice: The House I Live In features one man jailed for life without parole for being in the possession of three ounces (85 grams) of methamphetamine.

In 2010, President Obama overturned this rotten, racially biased act, and replaced it with a slightly less rotten, racially biased act. The Fair Sentencing Act shifted the crack/powder disparity from 100:1 to 18:1. But while there is still disparity, there’s still injustice. And this law is not retroactive – so none of those serving exorbitant sentences will be offered earlier parole - nor does it target the racial bias within drug sentencing or get rid of mandatory minimums. This was a valuable first step. But the President must do more.

Prisons

Jarecki’s film investigates how drug policy that fills up prisons has led to the development of a self-perpetuating prison-industrial complex. The U.S. has less than 5 per cent of the world’s population, yet it has almost 25 per cent of the world’s incarcerated population.

Highly profitable private prisons bring jobs and investment to down-and-out American towns, which means perversely many stand to benefit from the continuance of this failed and destructive policy. In many cases it’s almost impossible to close a prison because to do so would devastate the local community.

But something must be done. Speaking in The House I Live In David Simon, creator of The Wire, argues that “the political infrastructure is so consumed with the next election that there will never emerge a shred of leadership which will change the situation. It’s up to us.”

He’s right. Drugs are hugely destructive to communities, but by focusing on incarceration and splitting up families, rather than drug treatment and education, the Drug War is continuing to mutilate the future of another generation of young Americans.

There was never any scientific basis for America's drug policy, and there is none now. Obama should use his post-election boost to reform one of the biggest issues facing the criminal justice system.

The House I Live In is released in cinemas today

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments