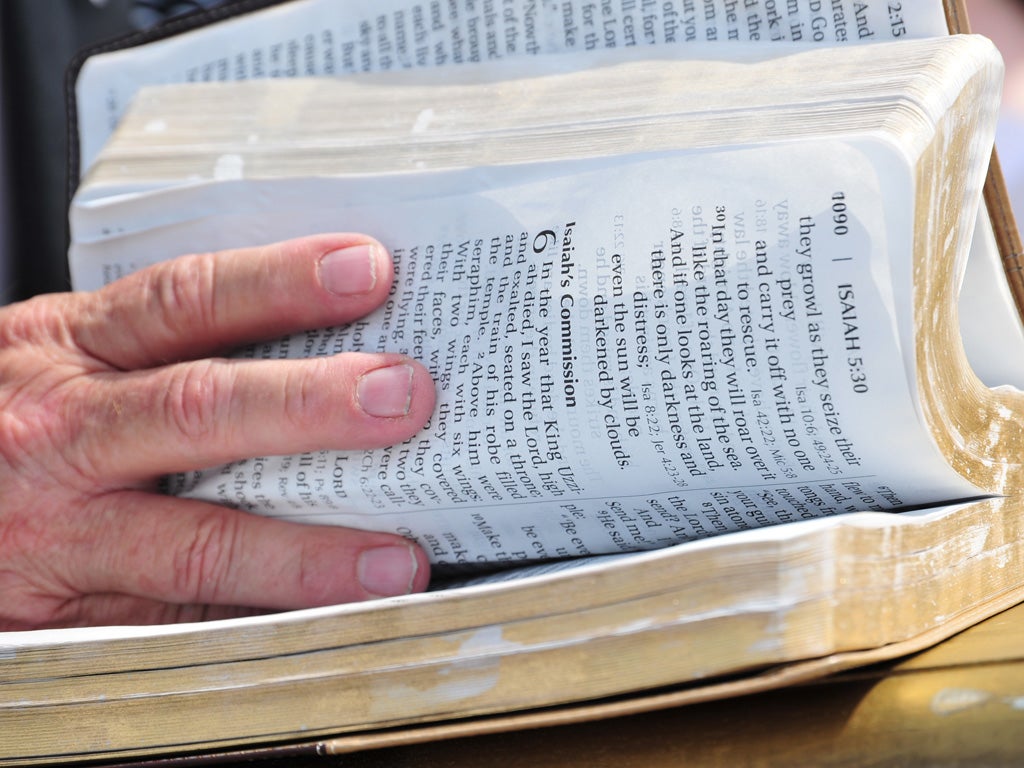

The census: are reports of the death of religion just being exaggerated?

You can be religious in the traditional sense, but not follow conventional traditions. The census should have asked about community.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is unlikely that if he were alive today, Mark Twain would have seen fit to comment on the results of the 2011 British census, esteemed survey though it is.

But to misquote him, are reports of the death of religion being greatly exaggerated?

At first glance, the results appear to confirm that in Britain, faith is no longer fashionable. Asked for the second time in census history “what is your religion”, fewer respondents said that they had one. Although Britain is still predominantly Christian, since 2001 the numbers identifying as such have dropped by 13 percentage points, down by four million.

While the numbers identifying as each of Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist or Jewish either rose or remained largely consistent, more than a quarter of respondents said they had no religion, up from 14.8 per cent ten years ago.

When surveys or news stories point to a supposed threat to religious life in this country – the Scouting oath being adapted for atheists, for example - the doomsayers tend to warn that society as we know it is on the verge of breakdown; that the community structure that helped make Britain great is collapsing with no word on its replacement.

Perhaps in another decade we will be a country of faithless degenerates, with no moral code or appreciation of compassion. Or perhaps we will be as we are today – but defining our identities differently to past generations.

When I filled out my census form, I responded that my religion was “Jewish”. It was a fairly simple question – I grew up as part of the Anglo-Jewish community and continue to live much of my life within it. But if the census had demanded that I dig deeper – for example, if it had questioned how actively observant I was, or whether I believed in every word of the scriptures, or even in God - it would have required further consideration.

Religion, at least in Western tradition, is and always has been about those things – sin, divine truth, posthumous judgment and so on – but it is has long been about much more besides. For me, and for many day to day adherents, religion is less about the wording of ancient texts or attending formal services, and more about tradition, lifestyle and community, and the centrality of values such as kindness and respect.

A decline in formal identification of religion points not at all to a decline in living good and meaningful lives; the Victorian conflation of faith and lifestyle surely no longer applies.

You can be religious in the traditional sense, yet use your religious identity as a basis to be intolerant or divisive (for example to justify the oppression of women) and likewise you can scoff at the idea of a man on a cloud in the sky, but still accept and advance the moral guidelines that happen to be promoted by religious thought. You certainly don’t have to believe in the truth of a religion to appreciate its teachings about how to live your life.

Without a population that places weight on such values, we might have cause to fear for the future. But there’s no reason to assume that the census results mean the core teachings of religion are on course to disappear. Look no further than the clean-up after the London riots – organised not in a formal hall of worship but via social media – or the many street parties held for the Jubilee, to see the community spirit alive and well in Britain.

There are many benefits to being part of a faith community. But it comes down to definitions – what do we mean by “religion” and how do we define “identify”. The census asked about religious identification as a label – not whether citizens believe in the value of community, or support the general ideas advanced by different faiths. If it had asked the latter, I suspect we'd be a lot more “religious”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments