The Bank of England is wrong to assume that falling unemployment signals rising wages

Over the past six years the Federal Reserve set policy and six months or so later the MPC followed

Last week the new chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen, gave evidence on monetary policy before Congress’s Committee on Financial Services. This was the first time she has spoken as the chair and her testimony was well received – the Dow jumped nearly 200 points on the day. Ms Yellen made clear that it was time to adapt the Fed’s forward guidance policy which had focused on the unemployment rate and which had fallen by nearly a percentage point since the middle of last year.

The first female head of the Fed said even with this decline the unemployment rate is still “well above levels that Federal Open Market Committee participants estimate is consistent with maximum sustainable employment” and went on to note how important it is to “consider more than the unemployment rate when evaluating the condition of the US labour market”.

In its Monetary Policy Report to Congress, issued on the same day, the FOMC noted there had been little improvement over the past year in either the employment to population rate or the labour force participation, where it argued that “some of the weakness in participation is also likely due to workers’ perceptions of relatively poor job opportunities”.

It also expressed concern that the share of the unemployed who have been out of work longer than six months and the percentage of the workforce that is working part time but would like to work full time have declined only modestly over the recovery. In addition, the quit rate, an indicator of workers’ confidence in the availability of other jobs, remained low.

We should note, by the way, that three of the ten current members of the FOMC are women (Ms Yellen, Sandra Pianalto and Sarah Bloom Raskin), with another one nominated and waiting to be confirmed (Lael Brainard), compared with none on the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee.

The next day the Governor of the Bank, Mark Carney, held a press conference where he announced that forward guidance based on the unemployment rate had been abandoned as it had fallen so fast over six months, from 7.8 per cent when he took office to 7.1 per cent now. Sound familiar?

The MPC’s concern is that the fall in unemployment overstates the fall in labour market slack or the scope for total hours worked to increase without pressure on pay. In his opening statement Mr Carney said the MPC would be monitoring a “broader range of indicators including unemployment, participation in the labour market, average hours worked and the extent of involuntary part-time working, surveys of spare capacity in companies, labour productivity, and wages”.

Over the past six years the Fed set policy and then, six months or so later, the MPC followed – rate cuts, QE, forward guidance, following the data and now un-forward guidance. Here we go again.

The Bank actually assumes, quite wrongly, that the long-term unemployed put less downward pressure on wages than the short-term unemployed. This sort of assertion was made in the 1980s, when it was shown to be entirely without foundation, by Andrew Oswald and I, and many other researchers; there is absolutely no credible empirical evidence to support such a contention. This likely means that the rate of unemployment at which wages will start to rise, that is full employment, is well below the 6-6.5 per cent the MPC asserts, which means there is more slack in the economy than it thinks.

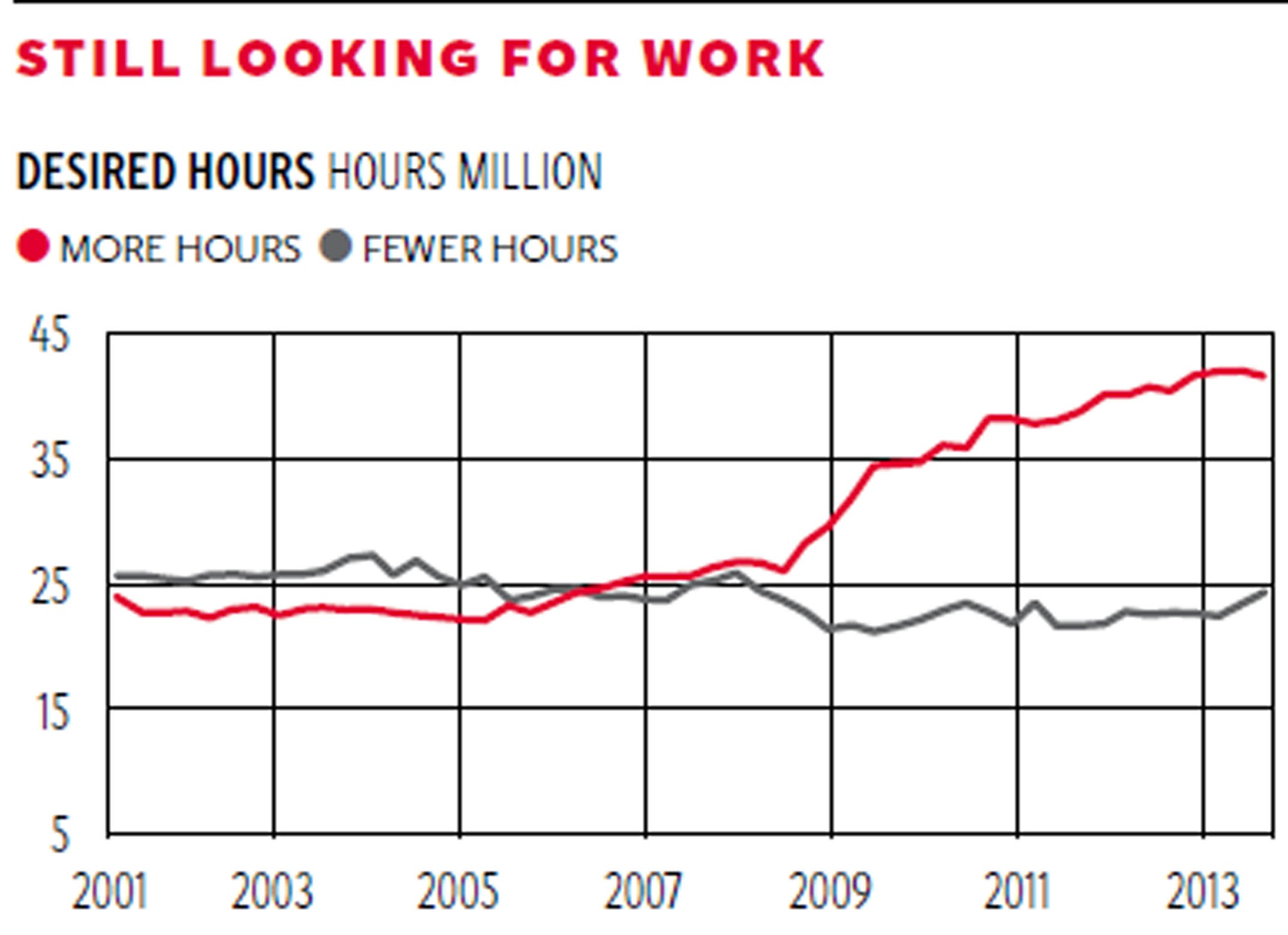

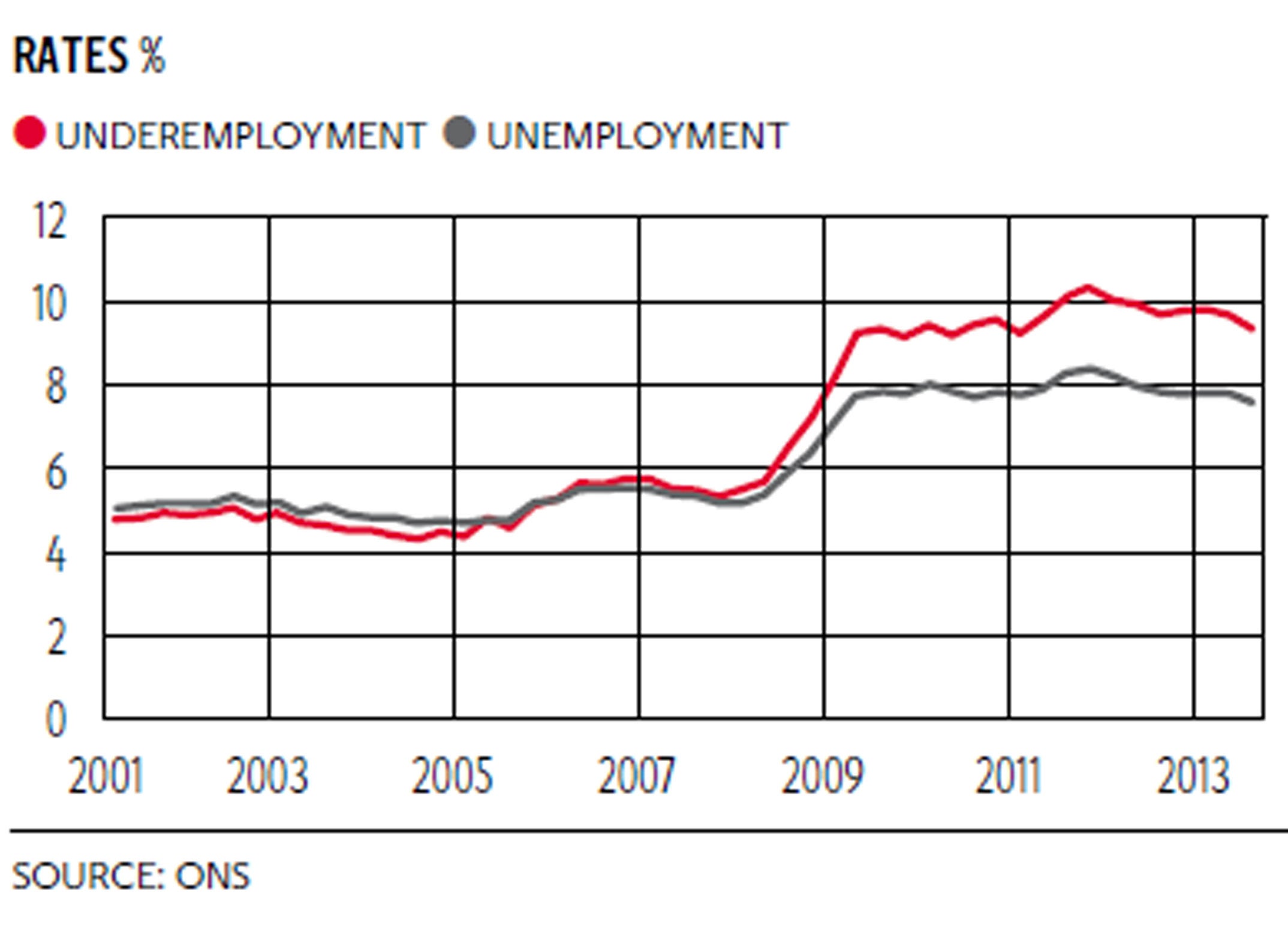

The MPC noted that despite the fact that the unemployment rate had fallen sharply there was little evidence of any improvement in real wages, which continue to decline. They also noted that despite the fact there had been an increase in average hours worked since last summer, from 32.0 to 32.2, “the number of people indicating they would like to work longer hours has remained elevated”. This is illustrated in the two charts that plot the underemployment rate that David Bell and I publish quarterly, with our latest estimate for Q3 2013.

The data are taken from the Labour Force Surveys and workers’ expressed desires for different hours calculated as the total extra hours workers who say they would like more hours at current pay rates want minus the hours of those who want hours cut. As the first chart shows, in the years up to 2008 the two series tracked each other, but since then the number wanting fewer has fallen while the number wanting more has risen sharply. This contrasts with the US, where the various measures of underutilisation track the unemployment rate with no widening. The second chart shows in the UK the two rates have fallen roughly together; the gap of around 17.5 million hours per week translates into over half a million extra workers based on average hours of 32.2. The implication is firms can increase hours without generating wage pressure.

The MPC made clear in its Inflation Report that interest rates aren’t going to rise while the recovery remains “unsustainable and unbalanced”. The hope is business investment will pick up while it has almost given up hope that exports will boost recovery. The MPC seriously hedged its bets, saying Bank Rate could rise more slowly than expected, or rise more rapidly. The expectation, though, remains that in future “the appropriate level of Bank Rate is likely to be materially below the 5 per cent level set on average by the committee prior to the crisis”.

This is somewhat of a worry given that the MPC will have little room for manoeuvre, should another shock come along. It surely will and then it would have little room to cut rates; most of its firepower would be used up. So QE would have to be back on the table again and again and again. Round and around we go. There is, of course, that house price bubble that is inflating every day … don’t worry that could never burst. Isn’t that what they told us in 2005?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks