Stockmarkets across the world are back to previous highs, but is that good news?

Rising share prices are yet another driver of inequality

The market is going up but the wealth is not trickling down. Or to put it less starkly, the rise in share prices is not giving as much of a boost to global economic growth as you might expect, given that we are seeing strong share prices early in the economic cycle, rather than at its peak as in 2000 and 2008.

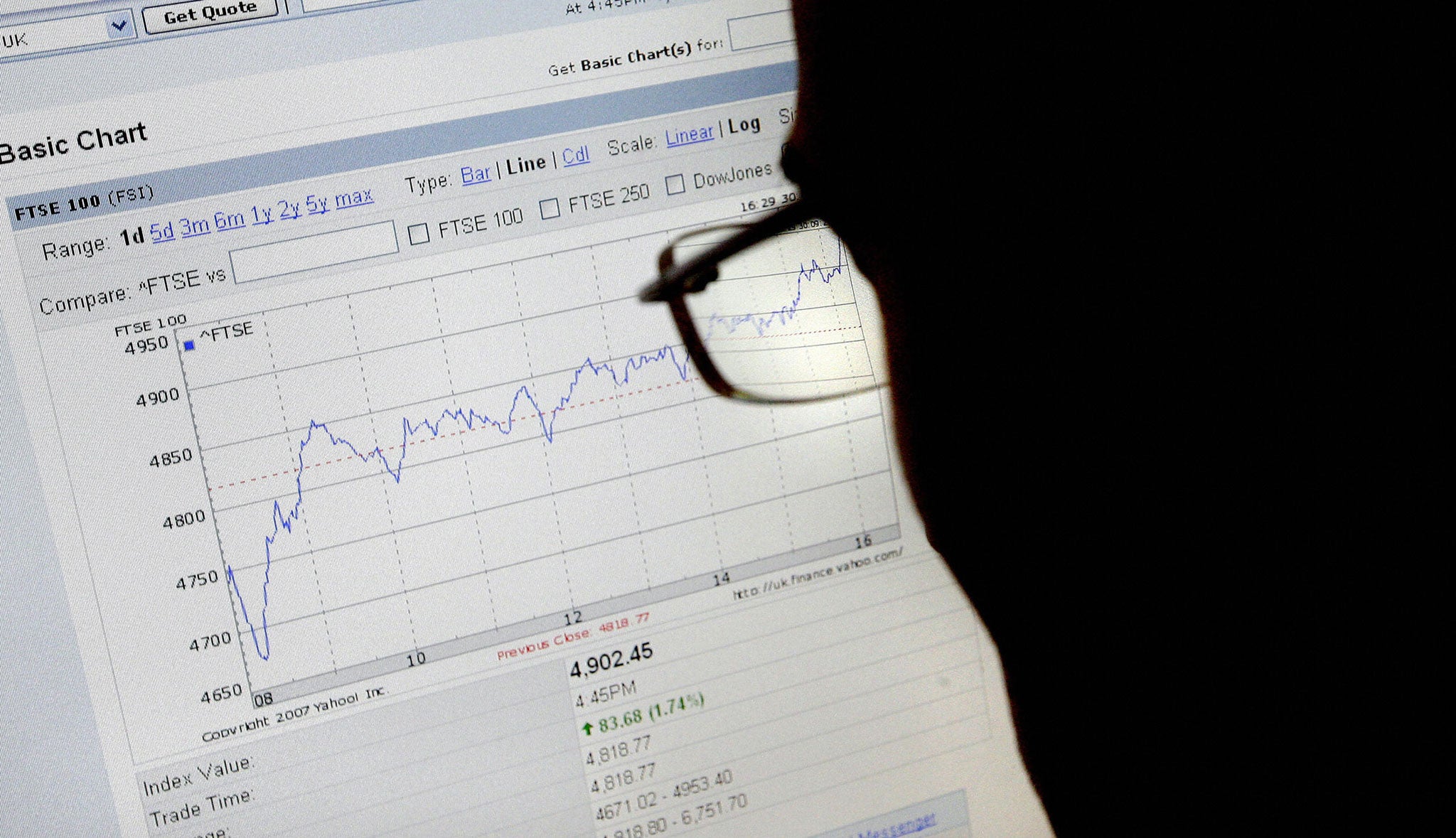

Shares worldwide are, with the exception of Japan, back to their previous highs: the Dow Jones is past its peak, and the FTSE 100 is within about 6 per cent of its own. That obviously contrasts with what has been a disappointing recovery, not just here but in the US and Europe, too. This has led to debates about the vulnerability of equity markets to a setback, the extent to which they are relying on the central banks to keep printing money, and, conversely, the extent to which markets are looking through present uncertainties and seeing solid global growth ahead.

But there is another debate about the effects of the boom, for share prices are both a function of economic activity and a driver of it. Strong share prices ought to make it cheaper for companies to raise money for investment, or at least give them an alternative source of capital to the banks. They ought to be repairing pension fund deficits, though our pension regulatory system has, some of us think quite madly, forced funds to run down their equity holdings, with the result that pensioners will not have reaped as much benefit from the recovery in prices as they should have. And, at the margin, those who own shares directly will feel more relaxed about their financial situation and maybe a little more prepared to spend money.

It would be nice to be able to predict the impact on final demand as a result of changes in share prices, but studies are not very conclusive. The scale of “wealth effects” is pretty hazy. So while the recovery of equities must help demand – it could hardly not – we have very little idea of how big the impact is likely to be and how long it might take.

That leads to a further issue: are rising share prices yet another force increasing inequality? Inevitably, yes. Insofar as the owners of shares are richer than people who don’t own shares, any rise in the markets increases inequality of wealth, just as an increase in house prices increases inequality. There may well be medium-term social benefits, for example if an increase in share prices encourages more people to save for their retirement, but in the short term it is a question of the “haves” having yet more. A high tide may lift all boats, but that does not help those without a ship.

This sense that we are not all in it together may account for the muted reception in the US to the Dow passing its previous record. This leads us into thinking about inequalities of wealth – their causes and what can be done – rather than the present focus on inequalities of income.

There are several strands to this debate. One is how to encourage savings, which actually have shot up since 2008, though mostly in paying down debts rather than building up a nest egg. Another is about pensions, for there is a growing chasm between those in the public sector and those in the private sector. Still another is the effect of falling owner-occupation on patterns of wealth: if the young are unable to get on an escalator, are they better off renting and building up other assets?

There are no easy answers, but the common-sense position that people ought to have some savings is at least a starting point, even if the Government’s policy of ultra-low interest rates would seem to undermine it. Meanwhile, the markets are rewarding people with a nest egg in shares, which makes a change from much of the past decade.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks