Sometimes a rut is just a rut. But sometimes, for an artist, it's a seam of gold

Plus: A query about Flight (with the breast intentions) and why James Joyce represents the true test of a translator's skills

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How do you tell the difference between a rut and a seam of gold? Not a difficult conundrum in life, to be honest, but a bit trickier when both are metaphorical. They share some things, after all, on a figurative level. Both are consistent and linear, for one thing – a vice in the case of the rut, from which you want to escape, but most decidedly not in the case of a seam of gold, which you're likely to want to last for ever. And if you're applying these images to an artist's canon of work, it can be tricky knowing which is which. The kind of artists I have in mind are those who refine their art to a single, sharply defined point, so that the work they produce in their final years is immediately identifiable by even the least sensitive observer. Mondrian, say, or Rothko, both of whom abandoned the fretful quest for novelty of material or subject matter in favour of an obsessive exploration of one essential idea. Were they stuck or were they mining, though?

My feeling with Mondrian is that he ended up in a rut, though that's obviously a subjective response. I've just never been able to tell the difference between a good late-period Mondrian and a bad one. Worse, I can't even begin to work out how you would tell the difference between a good late-period Mondrian and a bad one, and I have a sneaking suspicion that people who claim they can might just be faking it. And if discrimination between different individual art works no longer operates you sense that something odd has happened. It might not really matter at all that this line is here and not half a centimetre to the left, only that it is sufficiently Mondrian-esque to pass muster.

I don't feel the same thing about Rothko. I guess that's partly down to the fact that the paintings are more organic and expressive anyway, more obviously a register of human hand and emotion. But it's also perhaps because the paintings seem alert to their own furrowed intensity. One of the things they seem to be about is not being able to break away from this lowering intensity of mood. Rothko is in a rut that happens to be richly rewarding, artistically at least. It's a gold rut, if you can have such a thing, and it feels almost absurd to say of him (as I sometimes think of Mondrian), "Aren't you overdue for a new idea?"

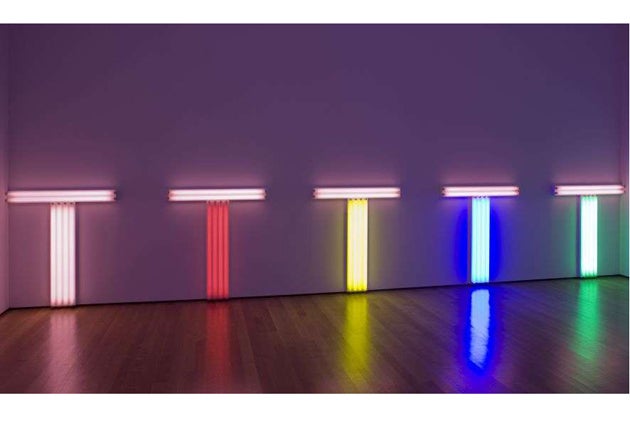

I found myself thinking about this while looking at an artist who, in my view, definitely found a seam, rather than ending up in a rut – the American artist Dan Flavin, who is featured in the Hayward's new Light Show exhibition. Flavin studied as a painter and then moved on to assemblages and collage, some of which included electric lights. In 1963 he made a piece from a single fluorescent light set at 45 per cent on the gallery wall, and from that point on he used no other material but commercially available, unmodified neon tubes and fittings. He became a minimalist, essentially – a branch of art which might be said to embrace the rut and glory in its confines.

But just take a look at Flavin's Untitled (To the Innovator of Wheeling Peachblow) at the Hayward and see what richness and liberation he achieves with his chosen restrictions. There's little point in looking closely at what the piece is made of because that will tell you nothing. Commercial light fittings in standard colours. What you have to look at instead is what the piece makes – a haze of rose and yellow light in the corner of the gallery that redefines the cruder colours from which it is mixed, and the white light that frames it top and bottom. It's lovely, so assured in its simplicity that you think, "Why would an artist want anything more?" Flavin found gold.

A query (with the breast intentions)

I found myself wondering whether Flight, Robert Zemeckis's film about an alcoholic pilot, can claim a dubious record: Fastest Nipple Reveal in a Mainstream Movie. The film begins with Denzel Washington's pilot waking up in a motel after spending the night with one of the cabin crew. As I remember it, Nadine Velazquez's breast is virtually the first thing you see on screen. Was Zemeckis sending a message? Don't think Back to the Future, guys, this one's for grown-ups? Or did he just figure there was no point wasting time getting to his money-shot? I would be curious – for reasons of film scholarship alone, naturally – if readers can offer any rival candidates.

True test of a translator's skills

The hardest day's work I ever did at university was the one I spent reading a single page of Finnegans Wake, attempting to identify as many allusions and multi-lingual puns as I could. So I shudder to think of the difficulty of rendering Joyce's text into Chinese, as the translator Dai Congrong is currently doing. She's just published the first third and has been encouraged in this literary act of self-harm by the fact that the book has become a surprise sales success. How you translate a book that can't really be said to be written in any existing language I'm not sure but Dai hinted in interview that she'd had to tidy things up here and there for fear that her readers would assume she'd mistranslated the original.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments