Shabbes exerts a pull on all Jews, and today is bigger than ever

We call it the day of rest, but I’m not convinced it’s rest we most need

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Good Shabbes. Unless it’s gone 6.44pm on the day this column is published, in which case it’s Shabbes no longer and I shouldn’t be wishing you a good one. Sorry to be punctilious, but that’s how it is with religious observance. You can’t be approximate.

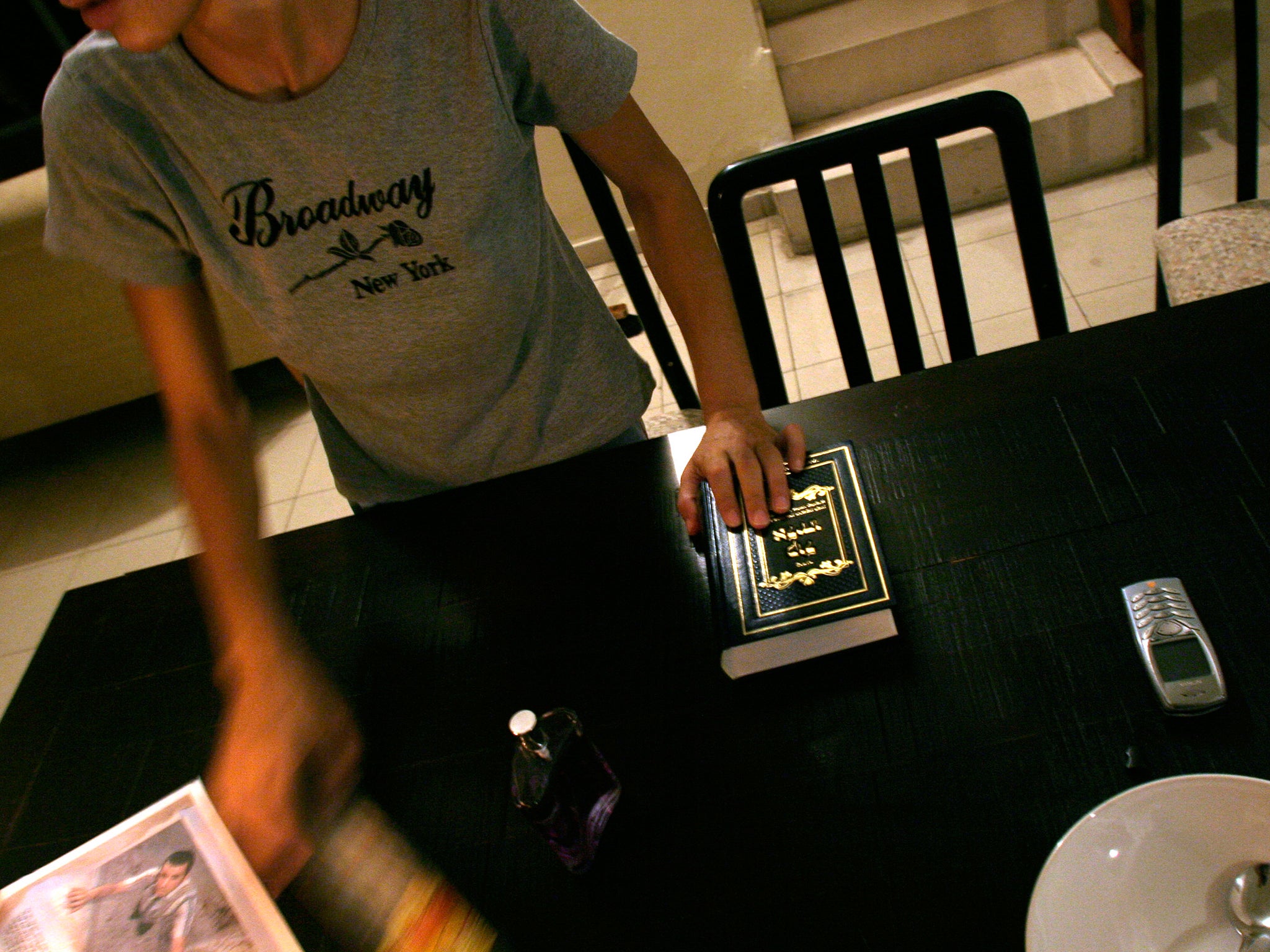

Which goes some of the way – all right, 86.55 per cent of the way – to explaining why I’ve never been a good Jew in the observing sense. What time exactly does a festival start and what time exactly does it finish; when, to the second, can I turn on the oven; what constitutes work precisely and what constitutes relaxation, and can it still be called relaxation even though it doesn’t relax me; if I can read a book congenial only to the spirit of Shabbes on Shabbes does that let Kafka in or Kafka out; and why shouldn’t I read The 120 Days of Sodom in bed on a Friday night so long as I pass adverse criticism on its obscenity – all this quibbling and cavilling presupposes a pedantic God, and since I don’t like pedantry why should I make an exception just because it’s divine pedantry, particularly on Shabbes when I’m supposed to be relaxing?

Today is a bigger Shabbes than usual in the Jewish world because it has been chosen to launch the Shabbos Project, or ShabbatUK – and if you wonder why there are so many different way of spelling Shabbes you put your finger on another problem I have with it. I knew where I was with Shabbes. I didn’t keep it. That made me a naughty boy, but my excuse was that my father was a market man and couldn’t have made a living had he not worked on Saturday and not had me to help him. In the robustly secular Manchester of the 1950s this was understood and forgiven by even the strictest rabbis. A man had to feed his family. But once Shabbes metamorphosed into Shabbat – for which blame creeping orthodoxy and Israeli pronunciation – what had been a venial omission, akin to letting down a friend, became a profanation of the sacred.

However it’s pronounced, Shabbes exerts a pull on all Jews. Probably the only Jews who think about Shabbes more than those who keep it are those who don’t. I don’t say that when I climbed into my father’s swag-filled van on Saturdays to drive to Oswestry or Worksop my thoughts were filled with the wonder of God’s creation – for that’s what Shabbes goes on commemorating: the day work on the world was finished – but I did sometimes fear there would be a price to pay for my impiety, and often regarded boys accompanying their fathers to the synagogue not with envy exactly but a sort of reverential curiosity. Were their hearts filled with a peace, a holiness even, that mine would never know? Were they made more serious by their religious devoirs than working as a market grafter, knocking out shepherd and shepherdess wall plaques and nests of tartan cardboard suitcases imported from Romania made me? I didn’t want to be those boys, indeed I scoffed at them, but I was still glad they were, so to speak, keeping Shabbes for me.

And there are good arguments, whatever one’s faith, for a day unlike every other. In one part of myself I am pleased to have seen the back of those monotonous Sundays of the sort Dickens evoked in Little Dorrit – “Melancholy streets, in a penitential garb of soot, steeped the souls of the people who were condemned to look at them out of windows in dire despondency. Everything was bolted and barred that could furnish relief to an overworked people... nothing to change the brooding mind, or raise it up.”

But in another I regret we have turned Sunday into one more day for driving out to shopping complexes and buying wider screen televisions. How does that raise up the brooding mind?

We call it the day of rest, but I’m not convinced it’s rest we most need. Just as I’m not convinced it was rest that God most needed on the seventh day. What had he done that was all that tiring? All right, he’d created the cosmos, set stars in the firmament, imagined great whales and winged fowls and cattle, and wished them a fruitful future, but he’d done this simply by expressing his desire that it should be so. Fiat lux. Let there be light. And then sitting back and admiring it. Reader, if only my job were as cushy. Let there be a column. Fiat columna. And lo, there was a column. And the evening and the morning were the sixth day. And for that I need to rest?

Let’s agree that this is not the meaning of the seventh day. The meaning of the seventh day is the necessity to separate and distinguish, the Hebrew word for which is “havdalah”. Having created, God now chooses to be uncreative. Between making and not making, as between the waters and the firmament, as between light and dark, and as between the holy and the profane, there must be separation. One thing is not another thing.

The moment in the Shabbes service that touches me most – philosophically – is the havdalah benediction. Not because it brings Shabbes to an end but because it recalls to mind God the Great Discriminator, who discriminated between down here and up there, between the mundane and the special, between Mamma Mia! and Mother Courage, thus enshrining discrimination as the act that makes us Godlike.

A second soul, with each of us for the duration of Shabbes, is said to leave after the havdalah service. Hence the sadness those who believe in such things experience as Shabbes ends. They feel diminished, single, unexceptional again. It’s a wonderful idea – that for 24 hours (25 to be exact) we accrue extra being. Let me be clear. I liked escaping the endless prescriptions of Shabbes to work the markets. We had fun. But it was just me and my dad irreligiously and ungrammatically flogging tat from the back of a van. No second souls came looking to take up abode in us in Worksop.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments