Scottish independence: Ireland since 1919 is a lesson for Scotland in what a Yes vote means

The last divorce from the United Kingdom was painful and acrimonious, but ended in harmony and prosperity. So why should independence north of the border turn out any differently?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Seventy per cent of UK citizens in the land voted Yes to independence, they left the UK, got a government of their own, and local officials transferred their allegiance to the new state. But you can still take an express train across the UK border to the capital of the independent nation without a passport.

For years afterwards – even today – the acronyms of Queen Victoria, Edward VII and George V adhere to the postboxes. “Royal” still adorns the name of the local automobile club, the yacht clubs, even one of the country’s finest hotels, and “Honi soit qui mal y pense” remains on top of many government buildings and courts.

So don’t sweat about the Scottish independence vote. It’s all been done before – in 1919, and in the following three years. True, the postboxes are now coloured green. its citizens carry an EU passport with a golden harp on the front and they use the euro, but Ireland’s towns and cities look a bit like Britain in the 1930s. Spared the Luftwaffe’s urban renewal programme by its neutrality in the Second World War, the Republic of Ireland – for it only shrugged off the Commonwealth in 1949 – boasts thousands of English Georgian houses, complete with 18th-century fanlights and streets named after Palmerston, Wellington, Victoria and a few miscreants like Wolfe Tone, Padraig Pearse and James Connolly.

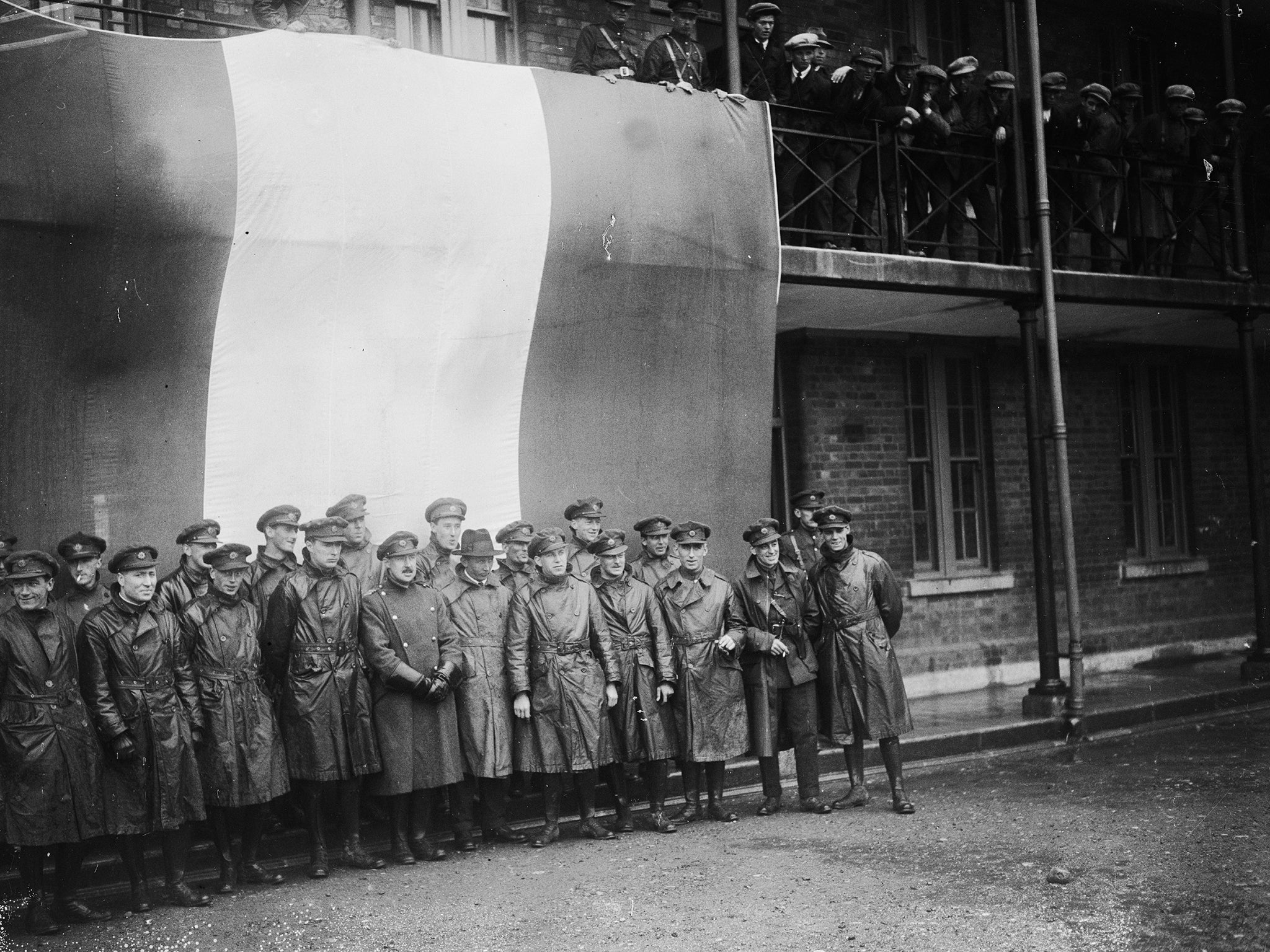

In other words, there is life after independence from the UK. The day the British left in 1922, the Union flag came down, the Irish Tricolour was hoisted over Dublin Castle – seat of their Britannic Majesties for hundreds of years – a UK Governor General (who was of course Irish) took his seat, and anyone lucky enough to receive mains electricity could turn the switch by the dining room door – and the lights came on, just as they always did.

Dublin had for more than 100 years been the UK’s second city, the jewel in the crown of the nation which ran an empire, and many visiting Englishmen were surprised to find that the Irish spoke English. In fact, like the Scots, they often spoke it rather better than the English. After independence, there was much economic hardship. Old age pensions were reduced. But the Irish “punt” was pegged to sterling, and remained so until in 1979 a dodgy Taoiseach – literally “chieftain”, a title for prime minister adopted, let us remember, in the age of fascism – “unpegged” it and Sterling moved a few pence higher in value.

Although the four great Irish regiments which fought so loyally in British uniforms in the Great War were disbanded, their colours were returned to the King in case Ireland returned to the Motherland. Some hope! The three great Royal Navy Treaty ports in newly independent Ireland stayed in British hands for another 16 years. But we handed them over to the Irish in 1938, thus losing them when we needed them most – in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Of course, there are some bleak differences between Ireland then and Scotland now. The Irish had fought for their independence in 1916 and been mightily and brutally crushed by the British army. Then they bravely fought the British all over again. Ireland’s 800-year history of English occupation puts Scotland’s misery into the shade. We won’t mention the Troubles.

But in Ireland, there was a place put aside for those 30 per cent who voted No – or would have done, if they hadn’t been square-bashing to fight both the Catholics and the British army. The Protestants were allowed to keep six of the nine counties in the north-east province of Ulster, and Belfast became their capital and industrial heart, the Protestants proclaiming their British citizenship with even more enthusiasm than the English.

In other words, the Catholic nationalists got Dublin, the Protestants Belfast. In Scottish terms, it was as if the Yes voters were to receive Edinburgh as their capital, but the Noes given Glasgow as a consolation prize with a few of the lowlands still in UK territory to keep them happy. Shipyards, courage and desolation mean that Glasgow and Belfast have a lot in common. But there, the parallels end.

The Protestant-Catholic struggle which divided Ireland (though not as much as the British think) has little or no role in the Scottish independence debate, save perhaps for the historical memory that Scots Protestant planters displaced Catholics in 17th-century Ireland. The Irish Yes voters – those 70 per cent who elected Sinn Fein to parliament in 1919 and set up the initially illegal Dail Eireann (Irish parliament) – broke apart in civil war before the British had even left the country.

But Scots beware… Irish nationalists fought each other not so much because of the border, which deprived them of six of the 32 counties of Ireland, but over the Oath of Allegiance to the British monarch. Those Irishmen who signed the initial treaty (Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith and the rest) insisted it would lead to sovereign independence, while those republicans who regarded the agreement as a betrayal thought it left Ireland effectively in British hands. De Valera notionally led this opposition – which lost the civil war – boycotted the initial years of the Irish parliament, then entered parliament as prime minister after a democratic vote – but without signing the oath. The Irish thus claimed they were independent when they were not, while the British could insist the Irish were still British at heart.

Another danger signal for the Scots. In 1932, De Valera decided Ireland would no longer pay debts to the UK government for loans given to tenant farmers when the country was part of the UK. The British introduced trade restrictions which bankrupted farmers and businessmen in Ireland. De Valera survived. Like Collins, he had fought in the 1916 rising, received a death sentence – later commuted – risked death on the losing side in the civil war, declined to fight for the Allies in the Second World War, yet saw his country triumphantly – if belatedly – join the UN. De Valera, as the great Constantine Fitzgibbon wrote, is one of the great survivors of the 20th century. And Alex Salmond is no De Valera.

But if it’s a Yes in Scotland, life will go on. There’s a crack train from Belfast Central to Dublin Connelly several times a day, so the Flying Scotsman will go on racing down from Edinburgh Waverley to King’s Cross without stopping at the border. These days, on the front of our passports, it says: “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland”. Note the “and” – because no one has ever decided whether Northern Ireland is really in the UK, a UK-protected “country” or a province. But it’s British. We think.

So if the Yes voters win, my guess is the Scots will insist they are independent while knowing they are not. And the British will claim that the Scots are still British at heart. And go on doing what they’ve always done: publish the work of Irish and Scots poets in anthologies of “English poetry”.