Politicians are promising to turn horses into unicorns this election

If what the party leaders say is true, we'll soon have full employment, no suicide, and a Labour politician capable of having 4m conversations in just four months

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We all know that politicians go back on their words. We remember, perhaps, Blair talking about Iraq, or Clegg talking about tuition fees. Clegg's broken promise is particularly galling, because he actually ran on the promise that he would “say goodbye to broken promises”. Although in his defence, he never gave an exact date.

It's obvious that all the U-turns of the last election are still fresh in the minds of the electorate, so the main parties have all moved into exciting new territory: rather than just saying they will do something and then not doing it, the politicians have adopted the strategy of saying they will do things that aren't actually possible, and then not doing them.

Liberal Democrats

Clegg is the best example. This week he has promised that, under his leadership, Britain will have a new “a new ambition for zero suicides”. He has promised to end suicide – but note the phrasing. He's actually not promised to end suicide, but promised to have an ambition to end suicide. So, if he fails, well, at least he tried.

If aspiring to end suicide is an ambition that sets the Lib Dems apart, then perhaps the most alarming thing here is the implication that the other two parties favour not ending suicide. Let's hope that is not the case.

The Conservatives

The Conservatives are doubling down on grandiose promises about the economy. Because they didn't manage to meet their deficit reduction targets this parliament, Osborne has promised to tackle them by the next parliament.

However, sixty per cent of Osborne's cuts are yet to come. The Office for Budget Responsibility, an independent watchdog, warned that “we might need to include an 'allowance for overspending' in our forecasts”. As some commentators have pointed out, in watchdog speak this means: “don't believe a word of this”.

Promising five more years of austerity is unlikely to excite the electorate, so the Conservatives have also made some unrealistic promises that sound more appealing. If all the spending cuts go well, by 2020 we'll get a tax cut, representing £6.8bn in additional government spending.

While all the spending cuts are happening and government jobs are being lost as a result, according to Cameron we will still be able enjoy full employment.

And, according to Osborne, despite the spending cuts, Britain will be put on track to becoming the richest country in the G7 by GDP per capita by 2030. Given the recent surge in US growth and the fact that the US already has a GDP per capita that is around 30% greater than the UK's, my feeling is that even 15 miraculous years of Tory governance are unlikely to make up the gap.

Labour

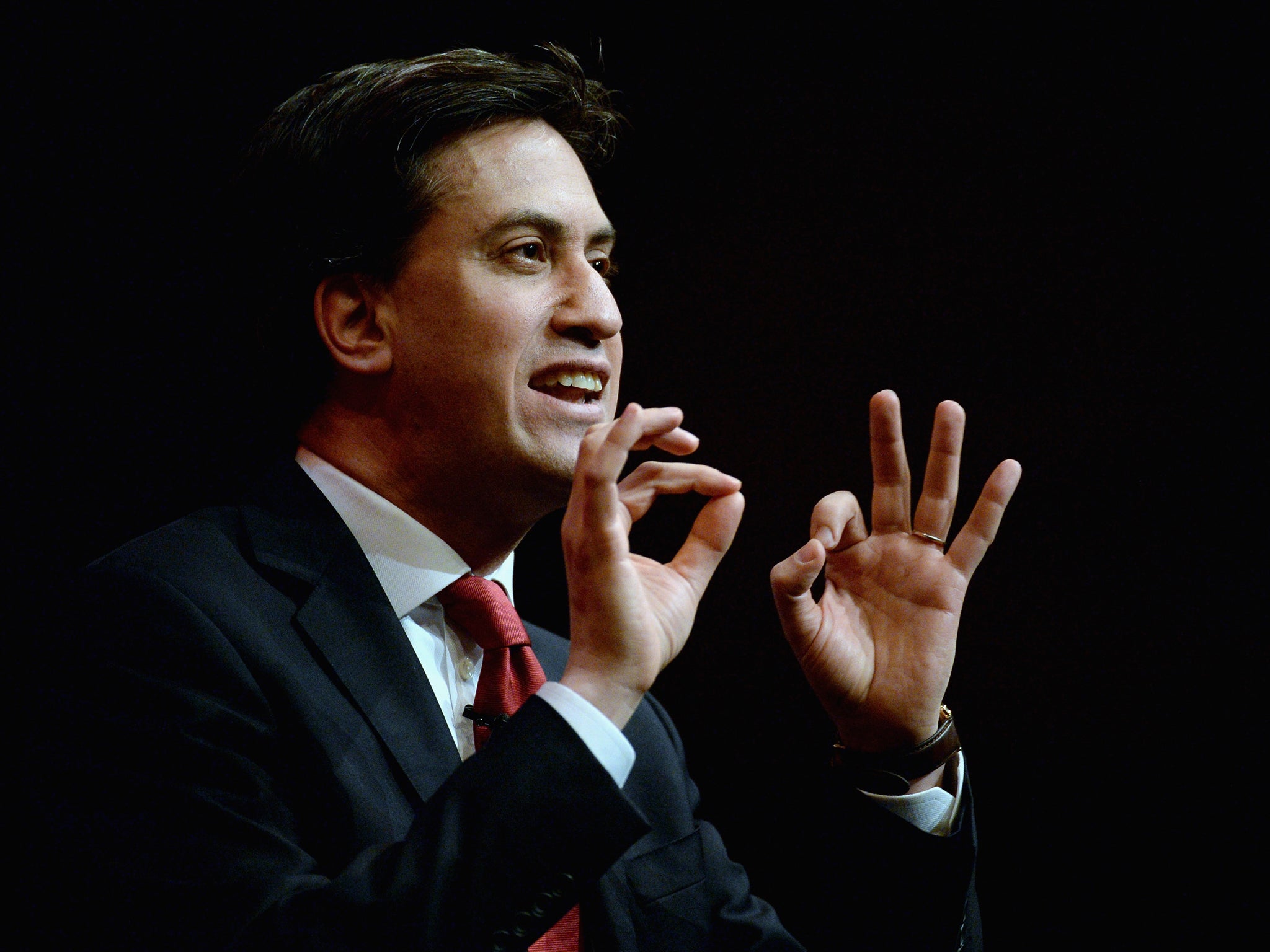

Labour, eager not to be outdone by the Tories or Lib Dems, have gone one better by making a promise that they will break before the election has even happened.

Miliband has pledged to have four million conversations with the public in the next four months, which, as The Guardian's Stuart Heritage has pointed out, will involve him having 2049 conversations an hour.

Perhaps in recognition that claims with numbers can be fact checked, Miliband has tried to keep the rest of his promises vague. He promises “hope over fear”, “fair rules” for immigration, to address racial inequality and to “change the UK”. He may as well be promising "good vibes" as well.

If the last election is anything to go by, we will spend much of the next parliament seeing just how egregiously the parties break all of these promises.

In the last five years we have enjoyed the Conservatives upsetting both sides for doing this. They enraged the left when they reneged on promises to not cut frontline services or initiate a top down organisation of the NHS. And they frustrated the right when they reneged on promises to put in place a “referendum lock” on the EU and to start to repay the debt by the next parliament (after removing the deficit).

What happened? The next parliament is only a few months away, and the government has borrowed £190bn more than it planned, and not yet started paying down the debt. Whoops.

To avoid embarrassment, the Conservatives have taken the radical step of trying to remove information about their 2010 promises from the internet. As Barbara Steisand found out, trying to hide things on the internet often has the opposite effect; let us hope David Cameron doesn't try to delete this article.

Gross misinformation is unlikely to suddenly exit the political scene anytime soon, but we need our parties to be a least slightly truthful. We need them to indicate what they might do, what they would like to do, and what reasonably could happen if they came to power.

We need to be able to trust that what they say isn't completely disingenuous. After all, an election where no one knows what they are voting for is barely more democratic than no election at all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments