Placing a transgender woman in a men's prison is a cruel punishment

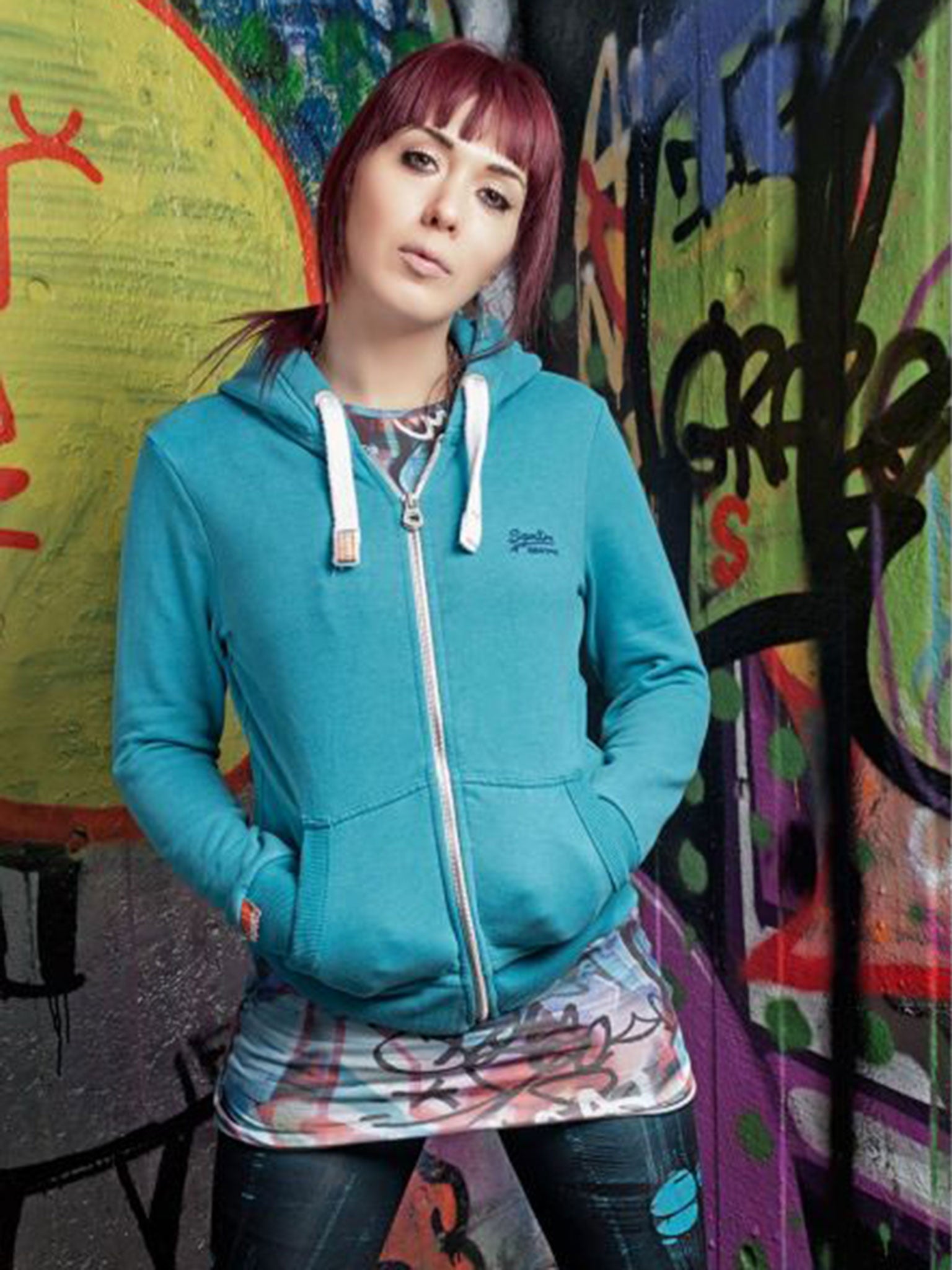

A number of high-profile cases have thrown a spotlight on transgender women being sent to male prisons, with tragic results. Paris Lees, a trans woman who has spent time behind bars, explains why reform and greater understanding are urgently needed

Last year, Tara Hudson, then aged 26, pleaded guilty to a charge of assault. She was sentenced to 12 weeks in the all-male HMP Bristol. Hudson was born male, but has presented as female since her teens. At the time, she says now, "I was kind of numb because it was all really, really surreal." After being taken from the dock, she was put inside a prison van with men. "That's when I knew that there was going to be problems. The boys on the bus were so confused, it was really scary. The guards didn't know what to do." When the van arrived at the prison, Hudson was removed first: "It just erupted. There was cheering and people banging on the windows." In the reception, other inmates initially assumed she was a member of staff: "When they'd seen me being checked in, they were just confused, and then they were cheering and making comments. Because I've got quite a large bust, I couldn't hide away.

"Once it started to be on the news, they were shouting from every wing, and it was a large prison," Hudson says. She describes her experience as "scary" and says she had to move cells four times because of the harassment, which included sexual bullying: "I was bullied into showing my boobs on numerous occasions so they could touch themselves while looking at them." At one point, she says, she even feared she was going to be raped: "I was left unattended with a rapist in the communal room, and he'd been very suggestive. I just kind of, I don't know, used my people skills to fend them off as best as possible."

Hudson is one of the lucky ones. Vicky Thompson was 21 when she took her own life last year. It was Friday 13 November and Thompson was alone in her cell in Armley, Leeds, in a prison full of men. Just before Christmas, reports emerged of another trans woman serving time in a male facility. She had injected herself with bleach and tried to remove her own scrotum through sheer desperation. "I cannot take no more," she wrote to the shadow women's minister Cat Smith. "I am a woman in a male prison and it is not right." Reading out the letter to Parliament, Smith also revealed that the prisoner had been raped and sexually assaulted during her incarceration.

As a trans woman and former prisoner myself, I've followed these stories with concern and I want to know: what is the Government doing for trans prisoners?

It was bad enough being "gay" in prison. I was born with a penis and, although I knew from my earliest memory that I should have been a girl, I hadn't come out as trans when I was sent down for robbery as a teenager. To the outside world, I was a skinny, feminine gay boy, one who arrived at HMP Glen Parva, Leicestershire, in tears. Inconsolable, I was placed on the hospital wing on suicide watch for the first three days. From there, I went to the induction wing, where I tried to keep my head down but couldn't escape homophobic abuse. Eventually, I was placed on a wing for vulnerable prisoners, which included a mix of sex offenders, "slashers", who'd attempted suicide, and a few middle-class boys who'd run people over by accident and found themselves in a hell of guilt and unexpected incarceration. I've been open about being banged up before because, as far as I'm concerned, I did the crime and I did the time. So I'm not calling for special treatment for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) prisoners. I do know first-hand, though, that prison is a particularly traumatic experience if you happen to be queer – and placing a trans woman in a men's prison is a cruel and unusual punishment.

"I assumed I'd be sent to a women's prison," Hudson says. Thanks to a high-profile campaign led by her mother and trans activists, 159,000 people signed a petition calling for her to be sent to a women's prison. It was raised in Parliament. The Ministry of Justice eventually caved in and transferred her to the all-female HMP Eastwood Park, but Hudson says this was due only to the media attention: "They'd have left me in the men's prison, if it wasn't for the public." How many more trans women are rotting away in male prisons whom we don't know about?

Hudson was initially turned away from Eastwood Park because the prison wouldn't accept her without a gender recognition certificate (GRC). In 2004, following years of campaign work by a dedicated team of trans activists, the law was changed to allow trans people to change their gender legally by applying for a GRC. There was no coverage in the mainstream media because, at the time, most journalists were interested in trans people only as punchlines or punch bags. Although the Gender Recognition Act was an important legal milestone, it hasn't aged that well. One benefit of getting a gender recognition certificate was to allow trans people to keep their trans status private, which was once widely seen as the holy grail of gender transition. As more and more of us are choosing to live our lives openly, and social stigma is slowly easing, that need for secrecy is becoming less urgent.

In fact, in 2016, many trans people don't feel they need a GRC. It's possible, for example, to apply for a passport in one's new gender role without having one. Added to this, applying for a GRC can be lengthy, complicated and expensive. As well as paying £140, applicants have to faff about with forms that make applying for a passport look no harder than writing a birthday card. People on benefits are entitled to help with the fee, but that means yet more forms – and, of course, you'd have to be aware that you were entitled to this help in order to ask for it. I know first-hand that many people who find themselves in prison come from poverty, broken homes and may well have left school early. They are not, in my experience, people who feel empowered or who are aware of their rights. As Tara Hudson told me: "I've been living as a woman for over half a decade and I don't see why I should have to go to a board and prove that I've been living as a woman for two years." She never dreamt she'd end up committing a crime or, indeed, that she would be sent to a men's prison if she did.

So what is the answer for trans people who are sent to jail but haven't changed their gender legally? The Government's recent Transgender Equality inquiry recommends that gender markers be removed from official documents such as passports. If society is to become more equal and less segregated along gender lines, this seems sensible. But where will that leave trans prisoners?

One solution being put forward is the introduction of a dedicated prison for trans people. Hudson's mother, Jackie Brooklyn, told The Bath Chronicle that trans people, like gay and lesbian people, are just as likely to find themselves behind bars as anyone else: "There'll always be those among them who break the law. But they are particularly vulnerable to the victimisation that is part of life in mainstream prisons… The Government has said it is going to close some of the worst old prisons and build nine new ones. That means there will never be a better time to build a prison just for LGBTs."

I'm not convinced this is an ideal solution. On the one hand, if I were ever to commit a crime and be given a custodial sentence again – which, I hasten to add, I don't plan on any time soon – I'd expect to go to a women's prison. I resent the idea that I would need to be segregated. On the other hand, until the Prison Service catches up on trans issues, maybe a special LGBT facility could save lives. If it stops any more women being raped and sexually harassed in men's prisons – or another desperate young person taking their own life – it's worth exploring. And it may well be the ideal place for the increasing number of people who identify themselves as "genderqueer": outside the traditional idea of a gender binary made up of men and women. Genderqueer people will fall foul of the law, too, sometimes.

"For the first two or three days, I wasn't allowed any contact with the women that were on that wing," Hudson says, of her eventual transfer to a women's prison. She was kept on a ward with women who were "really ill", as well as "a murderer who was there because all the other prisoners wanted to attack her". And this, she says, "is when I became suicidal". Hudson's story illustrates many of the ways in which trans people are frequently oppressed: the abuse, the segregation, the idea that trans women pose a potential threat to other women. And, of course, the constant questioning.

Hudson found one conversation with a senior member of staff at Eastwood Park particularly upsetting: "I just felt like he questioned who I was. I've lived my life for as long as I've lived it and I've never had to question myself. And it made me question myself. I thought: 'Who am I? The Government's against me; where do I come with my human rights?' I felt different. I felt discriminated against and I'd never felt that way before – not from the Government, anyway.

"When I was finally allowed to mix with other inmates, I wasn't allowed to go in their rooms. They thought that I could potentially attack or, I don't know, upset another inmate. So I was treated differently. It was horrible." Despite this, the other female inmates completely accepted her: "Everyone that I spoke to thought that the way that I was being treated was absolutely ridiculous."

So who does think that trans women should be put in men's prisons? Well, some so-called "trans-exclusionary radical feminists" (terfs). The clue is in the name, though many radical feminists who wish to exclude trans people object to the description. Confused? You will be. Especially by their obsession with penises. As one of them tweeted during Hudson's campaign to be transferred, "I don't think sending a violent individual with a penis to a women's prison is a good thing." This is a specious argument. It's prejudiced and unfair to suggest that Hudson or indeed any trans woman is a potential sex offender simply because they still have a penis. The idea that trans women pose a special threat, which other women don't, is bigotry, and unsubstantiated by evidence.

There is no evidence that trans women harm other women inside prisons. There is, however, plenty of evidence that trans people are vulnerable to attack by people who are not trans. Google "transgender woman attack" and you will find pages of incidents. Such as the two trans women who were "stoned in the street" in Germany. Or the trans woman "beaten to seizure" in the loos at McDonald's. By two women. Or the trans woman of colour who was beaten and shot to death by a large group of men. She was 19. There's a horrific catalogue of violence towards trans women, but nothing that suggests trans women pose any particular danger to other women.

There is also robust evidence that women in general are a danger to other women, at least in prisons. The US Department of Justice says that the rate of inmate-on-inmate sexual assault is at least three times higher for women than men in the US. Women abuse other women in prison. More than men abuse other men in prison.

Rather than waste time worrying about the imagined threat that trans people pose, supporters of equality should address the very real problems trans people face. Denial of health care, for example. The writer and political campaigner Jane Fae says the Prison Service is out of control, and that it ignores both legal duties and Ministry of Justice guidelines: "The more we probe, the more horror stories we uncover. Not just prison wardens, but governors who simply deny the reality of transness: officials who refuse individuals access to appropriate clothes or make-up; officials who remove essential medication, including hormones, despite the clear health risk to the prisoner; and when prisoners try to complain, officials who prevent prisoners from speaking to their parliamentary representatives."

Gender dysphoria is an internationally recognised medical condition, but you'd be forgiven for thinking that it was merely a quirk of modern British life, judging by some sources. I saw one tabloid headline recently that read, "Nine prisoners in same jail to have sex change operations on the NHS." Why is this newsworthy? And what is the implied alternative? To refuse trans prisoners medical care?

Fae says it would take a strong push from a progressive prisons minister to address governors who treat prisons as their personal empires: "Unfortunately, the prisons are run by Andrew Selous MP [the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Justice], a parliamentarian distinguished mainly for leading the opposition to granting trans people gender recognition in 2004." It's hard to see how reforms to accommodate trans prisoners can be made under such leadership. Fae isn't holding her breath: "It is likely that things will get worse before they get better."

I tried to arrange an interview with Selous, to give him the opportunity to respond to Fae's comments, but I was told that he was too busy to talk to me. Instead, I was fobbed off with a statement from a Prison Service spokesperson: "The prisons minister has been absolutely clear that transgender prisoners should be treated decently and humanely. Last year, he asked MPs to reflect on the violence still suffered by members of the transgender community and he made clear our commitment to ensuring transgender prisoners do not suffer discrimination." Was this the same speech, made on Transgender Day of Remembrance last year, when Selous told Parliament: "Prisoners are normally placed according to their legally recognised gender, which means either the gender on their birth certificate or the gender on their gender recognition certificate." And has he forgotten that he voted against the very laws that give trans people this right to change their gender legally?

The Prison Service assures me that "any allegation that transgender prisoners are being treated in an improper way will always be fully investigated. If anyone is aware of such treatment, we would urge them to report it to the appropriate authorities." Knowing Vicky Thompson's history of childhood abuse, her partner, Robert Steele, did just that. He called the prison to express concern for his "vulnerable" girlfriend, but that wasn't enough to save her life. We'll have to wait for the coroner's report before commenting further on her case, and a review of how the Prison Service treats transgender prisoners is also under way, but I worry it will take more suicides before we see any real change.

The death of Vicky Thompson moved me greatly, but her story is indicative of much deeper problems in the way that society deals with those who break the law. Prisons don't deter people from a life of crime and in many cases achieve quite the opposite. With insult added to injury, I suspect the Prison Service and most prison staff are like the rest of the population – woefully ignorant of what being trans means. In an ideal world, anybody dealing with the public – whether health practitioners, airport security, prison staff or police officers, not to mention journalists – would be given training on trans awareness.

I know through my work with the project All About Trans that simply meeting a trans person face to face, in a friendly setting, can have a profound effect on people. It is only when society sees trans people as people, and not a problem to be solved, that our existence will cease to be a problem.

Press for Change – legal advice on discrimination and human-rights laws for trans people (pfc.org.uk)

Bent Bars – a letter-writing project supporting LGBT prisoners (bentbarsproject.org)

Mermaids – family and individual support for teenagers and children with gender identity issues (mermaidsuk.org.uk)

The Transgender Equality parliamentary report on trans issues can be accessed at parliament.uk

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks