On an Istanbul street, have I just witnessed a positive step in history?

The people of Turkey are leading the way over the Armenian genocide. We wait to see if their government will follow

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A few hours before I sat down to write this article, I visited the tomb of Talat Pasha, the man who – in the eyes of those Armenians who survived his 1915 genocide – was Turkey’s Hitler.

He lies beneath a grey stone sepulcher under a grey stone arch on the Hill of Eternal Liberty, opposite the Florence Nightingale Hospital in Istanbul. Nowhere is it indicated that his date of death, 1921, was set by an Armenian assassin’s bullet in Berlin. Nor is there the slightest clue that it was Adolf Hitler who sent the body of the Ottoman interior minister back to Istanbul on a steam train decorated with swastikas in 1943.

Hitler hoped his gesture might persuade neutral Turkey to join the Axis side in the Second World War, which was a bit over-optimistic after the fall of Stalingrad. And the Turks, having lost their empire by backing Germany in the First World War, were not so stupid as to make a second fatal alliance with Berlin. But a Turkish friend has just sent me footage of the 1943 funeral in which Turkish troops can be seen taking this founding member of the Committee of Union and Progress to his grave on a gun carriage. I recognized at once the bleak little hill where I had been standing, with its independence obelisk – and noted the tall German military attache walking in the front row of the mourners, the ludicrously wide lapels of his Nazi dress uniform, his peaked hat decorated with eagle and swastika.

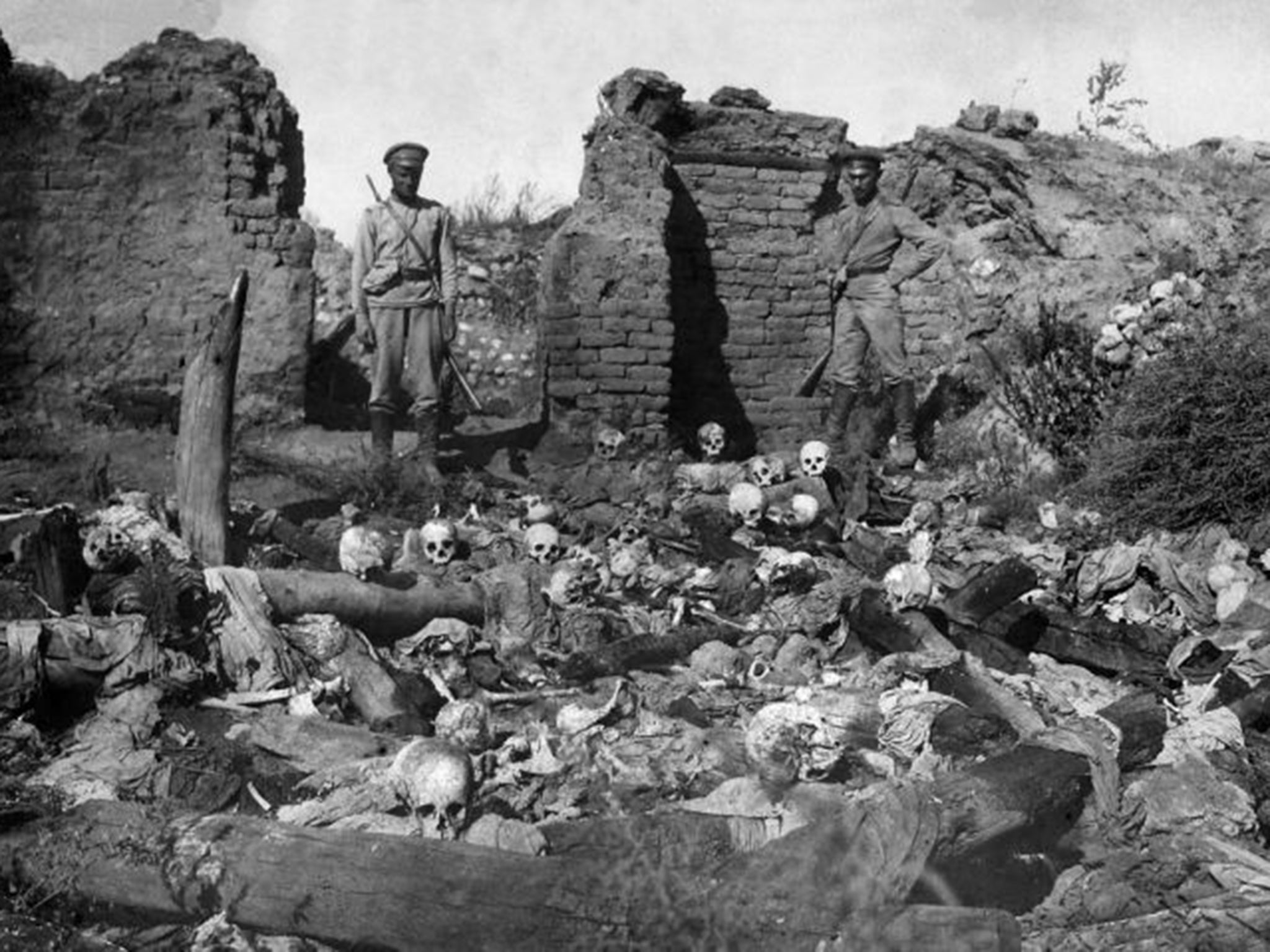

Most of those responsible for the last century’s first holocaust – including Enver Pasha, shot dead in 1922, whose tulip-smothered grave lies a few hundred yards from Talat’s tomb - were murdered in Europe or Asia by a group of vengeful Armenians in what they called ‘Operation Nemesis’, the subject of a gripping new book by American-Armenian historian Eric Bogosian. The Jews of Europe were not the only ones to hunt down their persecutors after the genocide of their people.

So what would these men have thought (let us have done with dead men ‘spinning in their graves’) if they could have watched, as I did last Friday night, a crowd of several thousand - perhaps 60 per cent of them non-Armenian Turkish citizens – standing to attention in honour of the Armenian dead of 1915 in one of Istanbul’s oldest streets? It’s rare that a journalist can report a happy story, however wicked its origins, and it’s unwise – as I did after the 2011 Egyptian revolution – to report, albeit with all the usual warnings, that this is a positive step in history.

But in Istiklal Street on Friday, watching Armenians from around the world recalling their people’s genocide, one felt as if history, in its arcane, almost comical way, suddenly moved into the future. “First, I invite you to a new beginning,” an Armenian woman, Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh, said in Turkish over a loudspeaker. “…Let’s work together for justice.” Then another voice, that of Nigaghos Tavibian, in English. “This is where it started…This is where Talat gave his fateful orders and this is the country where remembering was forbidden for 70 years…modern Turkey should have been built on the culture of all its peoples….We look forward to a day when the people of this country will say: ‘1915 – Not in Our Name’.”

The Turkish press, so used to adopting the same cowardly language as CNN and the BBC – that the planned extermination of the Armenians was “hotly disputed” by Turkey – printed the fearful word genocide more frequently than they did the usual gutless references to the “events” and “incidents” of 1915. And it was somehow pathetic that the best the Turkish state could do to wipe out the significance of the 24 April genocide commemoration was to falsify the date of its own sacred victory at Gallipoli by bringing it forward from 25th April. It made no difference. Putin shamed Obama by travelling to Armenia and called the 1915 mass murders a genocide.

Having withdrawn its ambassadors from the Vatican and Vienna to spite the latest nations to recognise the truth, is Turkey now going to order home its ambassador to Moscow? But the rules have changed. For the first time, the Turkish state last week permitted the Armenian patriarchate in Istanbul to commemorate 1915 – no mention of the “genocide” word, of course – and sent one of its ministers to the service. Though insufficient for the Armenians, President Erdogan told them earlier that “I sincerely share your pain”.

Non satis. To share pain, you must acknowledge truth. Which means genocide. When Turkish students at the Istanbul Technical University tried to commemorate 1915, campus guards attacked them with batons. And in the Armenian capital of Yerevan that same night of 24 April, in an act of profound stupidity, a group of youths set fire to a large Turkish flag in front of television cameras – thus proving to many Turks that the Armenians, far from seeking recognition of the genocide, still hated the modern-day people of the nation which tried to destroy their ancestors.

But then on Sunday morning, I found myself sitting in an auditorium of the Istanbul Bogazici University, listening to academics from around the world — including Turkey — discussing the Armenian genocide without any frightened quotation marks around the word, describing the outrageous property transfer laws which allowed the Ottomans to steal the homes and possessions of dead Armenians in 1915, and recalling the forced removal of Armenian orphans.

I interrupted my day, however, by visiting the military museum near Taksim Square. And there, in a glass case, I observed the shirt of Talat Pasha, still stained with the blood which poured from his head in the Charlottenberg district of Berlin on 15 March 1921 when Armenian killer Soghomon Tehlirian shot him in the base of the skull. Talat was not Hitler, of course. He was neither as efficient nor as fascistic as the Nazis. But he was a cruel man, still honoured in the land of his crimes.

So it’s tempting to ask which will win: blood or words? I’ll take a bet on what I’ve seen these past three days. A brave Turkey will acknowledge the genocide of the Armenians – and the Armenians should help them. The day will come.