Note to publishers: even authors have to eat

Notebook: How The Casual Vacancy could change publishing and why, thanks to Channel 4, we need a respectable new name for MDMA

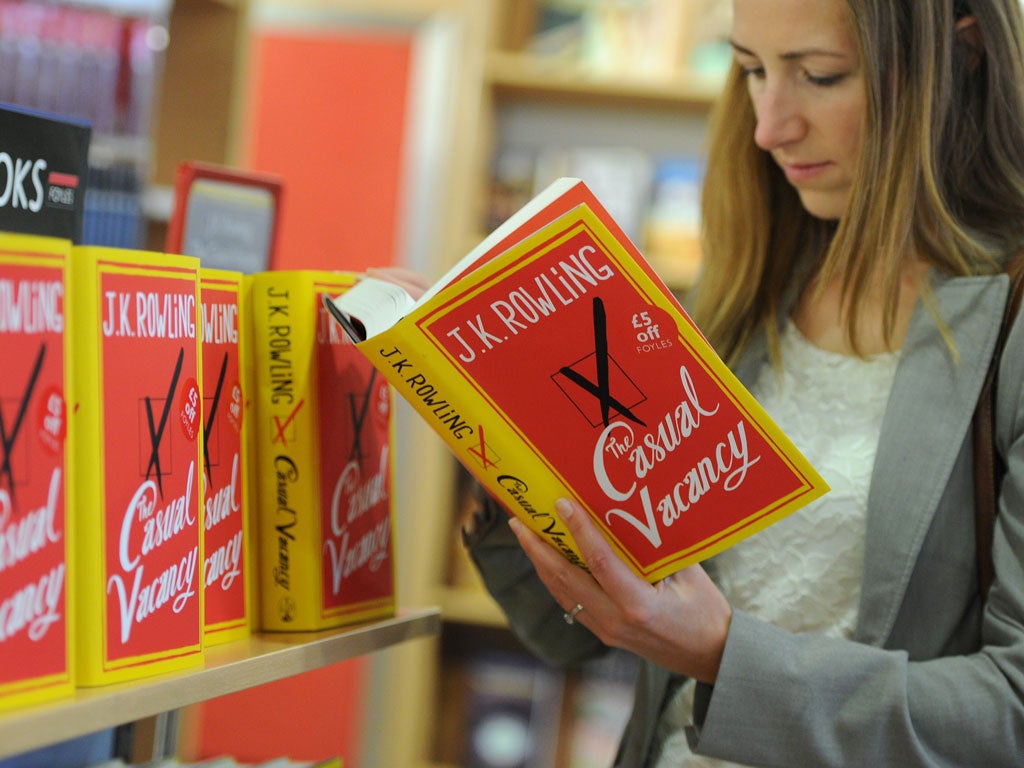

JK Rowling’s first novel for adults, The Casual Vacancy, came out this week, and with it a slew of profiles. These reminded us of the Harry Potter author’s struggles for fame, and the humble beginnings of her world-conquering series. The first Harry Potter novel was given a publisher’s advance, we are told, of £1,500, which, for a first novel in the late 1990s, was probably on the careful side for a company like Bloomsbury.

The rights to The Casual Vacancy were, on the other hand, sold for a sum that we are not being told about. Fortunately, we have now reached the point where interviews are being conducted not just with the author to promote the book, but, when she is unavailable, with her editor, her agent, and previous editors, now dismissed. Her agent, Neil Blair, was asked directly by one interviewer whether it was true that world English language rights in the book, dismissed rather sharply by many reviewers, had been sold for $50m. He denied it, saying that he was good, but not that good; from which one concludes that the figure has been exaggerated, but is very substantial indeed.

People from outside the publishing industry may wonder why a novelist who guarantees a bestseller may need an advance at all. Why not rely on the huge sales guaranteed by a readership which grew up with Harry Potter and is now ready for adult fiction in the same voice? The answer comes, in part, from the retailers.

This morning, I found The Casual Vacancy, which bears a cover price of £20, for sale at Tesco and on Amazon for £9, and even one retailer that was selling it for £8.42. Now I know that proper, respectful readers like you and me buy our books from independent professional booksellers at full price, so that writers can continue to eat, but that is not true of everyone. Ms Rowling and Mr Blair cannot be expected to carry on with their lifestyles on the royalties accruing from a few full-price sales in John Sandoe.

How writing is to be funded is a fraught issue, and one of the first signs of things changing is a court case just now proceeding in the US, taken out by Penguin against 12 authors who it claims failed to deliver manuscripts. Elizabeth Wurtzel, who wrote Prozac Nation, received a $33,000 advance on a $100,000 contract; she is being sued for the return of the money paid out plus interest. Other authors are being sued for less, including a New Yorker writer and Bob Morris, who is writing a proposed narrative about fishing lures, for the relatively trivial sum of $20,000.

This is a new development. The authors were certainly in the wrong in not delivering a manuscript, but, in the past, publishers would have considered whether it was worth the hassle and the terrible bleatings which resulted from writers. It is easy to imagine agents deciding to leave Penguin America off their submissions list for a brilliant but flaky first-time author. Non-delivery is a fairly clear-cut case – they took the money and didn’t write it. But what happens when a publisher decides to sue an author for the return of an advance because it doesn’t sell as well as they hoped, or because it doesn’t prove up to scratch?

The Casual Vacancy will probably earn an immense advance out of readerly curiosity, despite the huge discounting, but what about a third or fourth adult novel by Rowling given as mixed reviews as this one has? Would not a publisher start to think about asking for the tens of millions back? Joan Collins won a case in 1996 when Random House sued her for the return of what it claimed was a substandard novel. When is another publisher going to try its luck?

We can look back at an age when authors got modest, reasonable advances; where books were sold at protected prices, thanks to the Net Book Agreement; where a range of authors, publishers and independent bookshops made a good but not extravagant living, and conclude that the market may have been tampered with, but at least literature then could be funded through its own efforts, and feel secure about its future.

Let’s just change this drug’s name

Forgetting that there is really nothing more boring than watching other people take recreational drugs, Channel 4 this week asked a group of eager but respectable volunteers to take the drug ecstasy, or MDMA. It was previously very popular among clubbers in the 1990s, but in recent years has moved into the shade of more toxic pleasures such as ketamine, GHB and mephedrone. There has long been an argument for the use of ecstasy for therapeutic reasons; some studies suggest that it can help with post-traumatic stress disorder.

What is needed, however, is a new and suitably dull name for the drug, since MDMA has long ago been co-opted by recreational users. Just as heroin seems perfectly all right when it is called diamorphine and used in hospitals, so ecstasy could do with being rechristened something like vasodiethyline-7 and administered by a man in a white coat and half-moon glasses, rather than a bloke in a baseball cap who calls his customers “Geezer”. Whether it would work in the same way is an interesting question. Everything is performance, including the processes of intoxication, and medical professionals may find that though the white coat is necessary for the licence, a faked-up nightclub in the basement of the clinic may be necessary to achieve the drug’s beneficial effects.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks