My shameful secret: an ancestor of mine was a slave owner

For a part of my family it appears a system of torture and oppression proved profitable

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I discovered yesterday that, on 8 February 1836, a possible ancestor of mine (a great-great-great something or other) received a quite sizeable payout, totalling £118 and 16 shillings, from the British state. What it was for, you might be able to guess from the date. But I wouldn’t be sure of it.

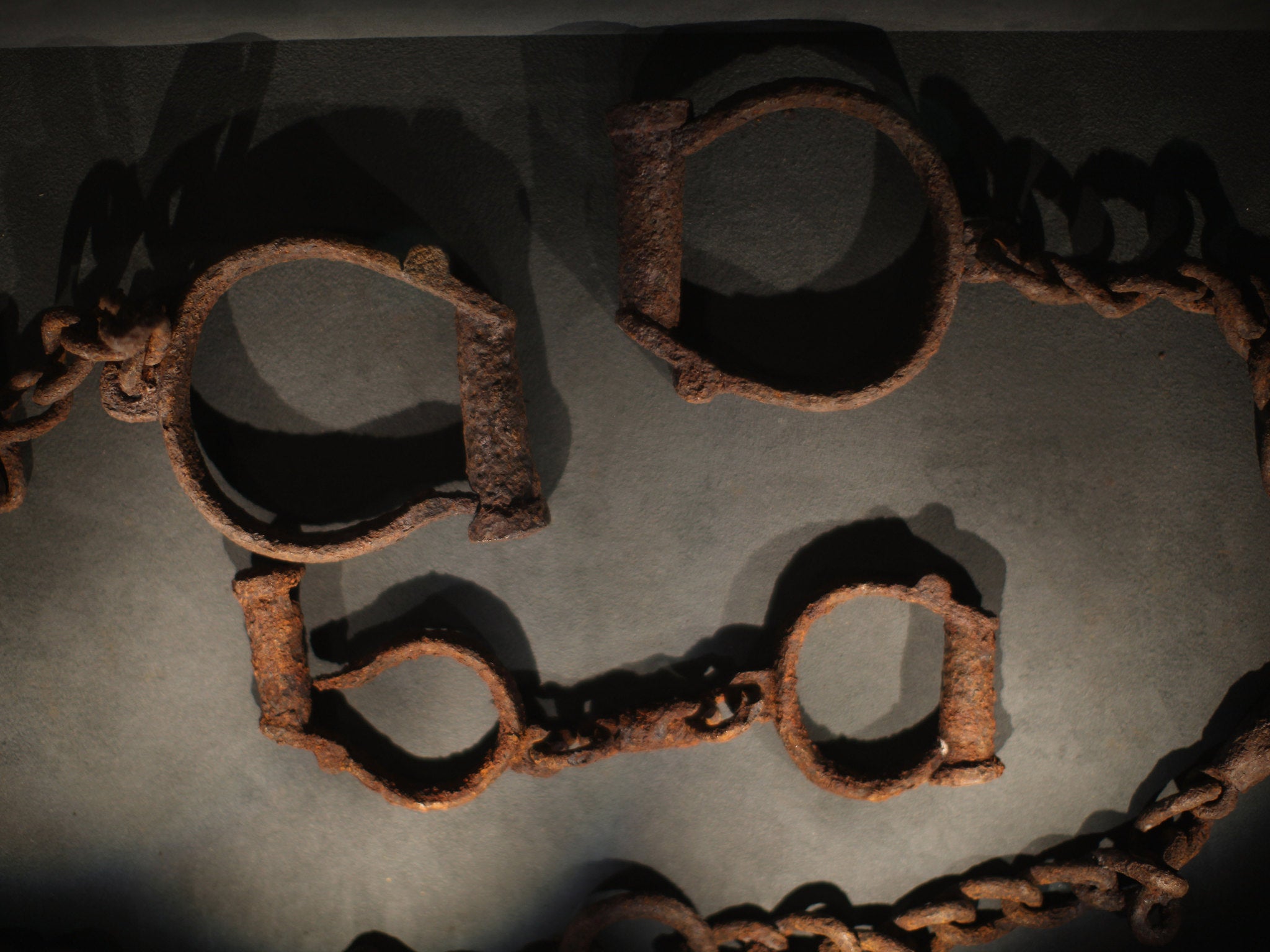

In the same way that I had no idea my family might have owned slaves – even as we studied the trade at school, the shadow did not cross my mind – few care to remember that when Charles Grey’s government declared, in 1833, that no man could be the property of another, it also saw fit, in rather less idealistic fashion, to compensate slave-owning citizens for the loss of their manacled and sweating human assets.

Mrs Elizabeth Peel owned six slaves on a Jamaican plantation. I know nothing about her or her life, but the name appears alongside 46,000 others on “the legacies of British slave-ownership” database, opened to the public this weekend by University College London.

Of course one feels a sense of shame. Initially on behalf of my ancestor, who may have been a darling in a bonnet, but who one still wishes – selfishly – had stood against human bondage rather than go with the wind. Those were different times, true. But how much easier to make that point when one stands in credit from the bloody affair.

For a part of my family – like so many others, like so many nations – it appears a system of torture and oppression proved profitable. A debt of £118 was paid by the government to Mrs Peel, to cap however much more her slaves had brought in harvesting the sugar that sweetened the family’s tea.

Across the country, Grey’s government bailed out slave owners to the tune of 40 per cent of GDP – a figure that dwarfs the 2008 rescue of the banking system. Today a debt remains on the ledger book, a hazier one, owed in a different direction, from the beneficiaries of slavery to its victims.

First is a debt of acknowledgement. To realise that one’s family tree isn’t peopled by William Wilberforces, stretching back through the ages; to admit that, historically speaking, one may have a touch more in common with the villains of 12 Years a Slave and Django Unchained than one felt at the time, loathing them from the back of the cinema; to reset, at least a little, the family compass.

I smirked at reports that a genealogy show had traced Ben Affleck’s family tree back to slave owners, a revelation which the actor had tried and failed to cover up. It seems odd now that I felt so sure – him being a Yank – that we weren’t in the same boat.

To find a likely predecessor on UCL’s “legacies of slavery” database, or simply to know of others who owned slaves, amounts to an awkward but unavoidable extension of one’s circle of relationships in the world.

I’d guess that descendants of the men and women bound to Mrs Peel can be found alive today (though their predecessor’s names are not to be found on UCL’s website). And free as they are to forget an acquaintance with the Peel name, to move on, that freedom is a one-way street. It does not work both ways.

Better, more accurate remembrance is the least owed by those – Mrs Peel’s offspring and those of the other 46,000; Britain, America and the other countries implicated – that creamed a portion of their riches out of slavery. “What is needed,” wrote Ta-Nehisi Coates in The Case for Reparations, his 2014 call to arms for The Atlantic magazine, is “an airing of family secrets, a settling with old ghosts”.

For enough time now, those who have had everything to forget – uprooting, poverty, shackled labour, rape, years of struggle for civil rights, a continuing fight with systems suspicious of black people and slow to let them rise – have had to do almost all the remembering.

Tomorrow, the BBC is to screen Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners, based on UCL’s data, which ought to nudge the conversation forwards. We await, possibly, Channel 4’s more controversial attempt to reunite the victims and beneficiaries and make Britain face its past, live.

Can acknowledgement in this way – talk, teaching and television – be sufficient balm for historical wounds? Its value cannot be overstated. But I expect I will not be the only person who finds an unwanted connection on that database and does a little more than wonder about the compensation their ancestors received.

Twitter: @memphisbarker

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments