My message to today’s A-level students: seize the future

Twice as many young people are jobless compared with my A-level year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What a different world today’s A-level students are stepping into, compared with the one my friends and I faced when we ripped open our results envelopes just over a decade ago.

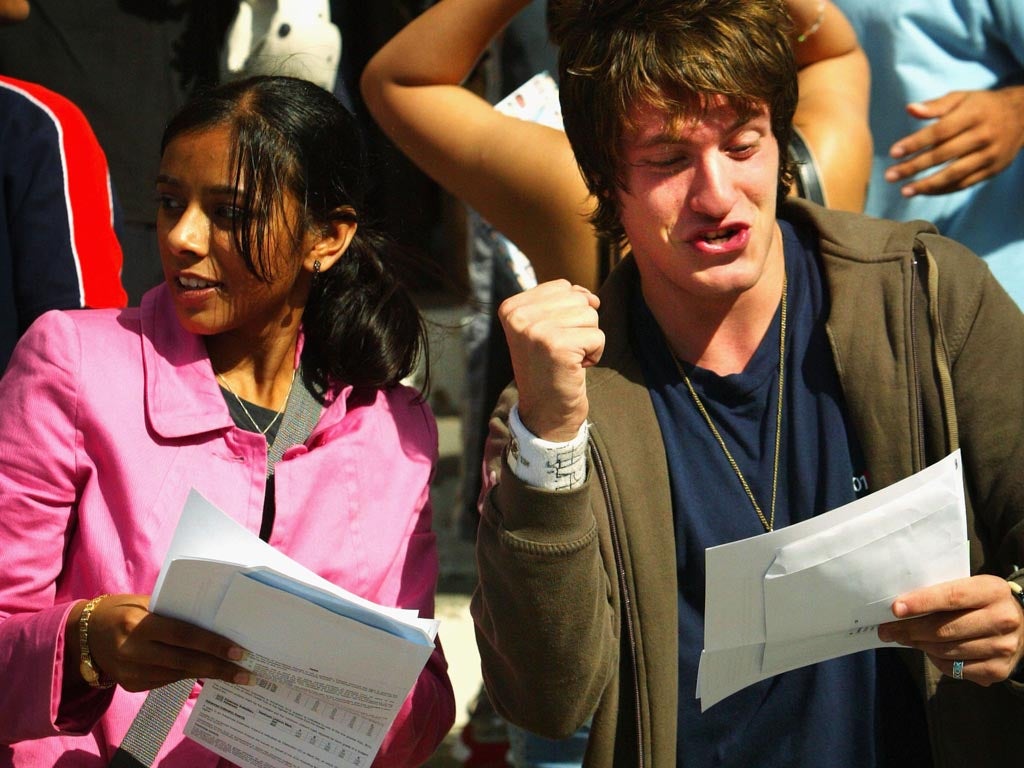

Sure, the similarities are there. That heady mixture of anticipation, excitement and fear; the shrieks of joy, the hugs, the weeping, the couples smooching, the looks of resigned disappointment; the sudden realisation that adolescence is over, normally flushed away with cheap lager and happy hour cocktails, and maybe an awkward fumble between long-standing friends. And there’s the newspapers filled with gratuitous photo shoots of attractive young women, ecstatically jumping in the air, and raging debates about what the results mean about standards.

But it is a different era. When the main quad of Stockport’s Ridge Danyers Sixth Form College was thronging with excitable 18-year-olds in 2002, Lehman Brothers’ logo was still glistening in Canary Wharf and New York. Britain apparently was in the midst of a never-ending economic boom. The GDP figures for the previous year were seen as a slight disappointment because the economy had grown “only” by 2.2 per cent. There were a million fewer unemployed people, and living standards were rising, generally, across the board. New Labour had introduced tuition fees four years earlier, but the ceiling was set at £1,000 a year, nine times lower than it is today. Graduate unemployment was gradually falling. It was months before the already monstrously unpopular US President George W Bush launched Shock and Awe against Iraq, politicising a wave of young students who took to the streets in the age of the so-called “war on terror”.

It would be beyond grouchy for me to ruin the day with frightening or doomsday predictions about what lies ahead for today’s A-level generation. The hard work of thousands of students and teachers will be reflected in results that will rightly be a source of pride and vindication. Those who go to university will meet lifelong friends, possibly even their life partners; they will learn things – both as academic and social beings – that will transform them for ever. Others will find jobs that are fulfilling and allow them in time to support a family.

But blimey, there’s no point pretending: things will be considerably harder than they were for me or my peers. A government that justifies its austerity programme with chilling warnings about saddling the next generation with debt will leave today’s university leavers paying off £60,000, in many cases for the rest of their lives. The number of students – generally from poorer backgrounds – having to work during term time to cover costs is much higher than it was, despite research suggesting it lowers grades. And neither are those who amass these excruciating debts guaranteed work: one in 10 graduates are now jobless six months after leaving university.

Overall, there are twice as many young people languishing in unemployment as there were when Stockport’s state schools had finished with me. And there’s no point glorifying the situation of many of those who actually find work. A third of university graduates are now doing jobs that don’t require degrees, up from a quarter a decade ago. A million people – many of them young – are stuck on zero-hour contracts, a disturbing echo of a supposedly bygone era when mostly young men would trundle to a yard in the early hours to find out if they had any work that day. Others are among the record numbers of workers forced to do part-time work in a country where 6.5 million are looking for jobs with more hours. There’s the booming poverty wage jobs, too: TUC research shows that nearly four in five of the jobs created since June 2010 pay less than £7.95 an hour. Whether they go to university or not, many of today’s A-level students will be fodder for Britain’s increasingly low-paid and precarious workforce.

There are other factors, too, that are conspiring to ensure the fresh faces of Britain’s future will be poorer than their parents for the first time since the Second World War. A housing crisis that has festered since the 1980s will leave many having to choose between joining a five million-strong social housing waiting list or being forced into a private rental sector charging rip-off rents and offering insecure tenancy agreements.

Despite strenuous government denials that their trebling of tuition fees would not deter students, the number of applications has yet to recover to their 2010 peak. Even then, it is claimed that low-income students – who are far less likely to apply – have not been deterred. It is difficult to quantify how true this is, because the figures are based on neighbourhoods, thus – for example – overlooking whether poorer students in better-off areas have been put off or not.

There are other models that are worth considering. Take Germany: in their dual educational system, vocational and academic qualifications are treated with equal respect. Most young Germans complete an apprenticeship, where they balance time working for a company with formal education. Transplanting that system to Britain isn't straightforward: modern industries would be needed to support the apprenticeships, and it would have to avoid falling into the trap of segregating working-class people into vocational qualifications, leaving the academic courses for the middle-class youngsters.

But if I had a message to today’s A-level students, it would this. As frightening as it all seems, don’t be depressed or beaten down by it. There is no better education than learning how to fight for your future. Look to Germany, where tuition fees are now being abolished. Fight for a living wage and the abolition of precarious, hire-and-fire contracts. Demand an industrial strategy, where the Government intervenes to create hundreds of thousands of renewable energy jobs to provide dignified, skilled jobs, backed up by properly paid apprenticeships. Call for councils to be allowed to build homes, again creating jobs but also helping to ensure you have an affordable home to look forward to. If you go to university, link up with those working there – whether they’re a cleaner or a professor – to fight for a place of learning that isn’t a consumer product, but a social good. Fight for a Britain where you are taxed based on how much income and wealth you have, not on how educated you are.

Of course, that can wait. Tonight is about shots, happy hour cocktails and awkward fumbles with people you shouldn’t. But when the hangover has passed, think it over, and don’t let them take your future away from you.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments