Margaret Thatcher - the dogged climber who pulled the ladder up

Baroness Thatcher did little to help less privileged women, believing the battle for women's rights had been won. She was talking about herself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Thanks to Margaret Thatcher, every girl born in the 21st century knows that a woman can be prime minister. It's an achievement, even if the party she led has stuck resolutely to male leaders since forcing her from power. No woman has even attempted to lead the Conservatives since Thatcher challenged Ted Heath in 1975, and this week's ceremonial funeral marks her official transition into history.

Last week her admirers preferred to dwell on what they saw as her achievements rather than the circumstances of her death. But just as the death-beds of saints were a popular subject in Renaissance art, there is something almost painfully expressive about the nature of Thatcher's passing. Many elderly people are lonely, with family and friends dead or scattered to the winds, but few end their days in the sterile luxury of an expensive hotel.

The image of this frail woman dying in the Ritz, attended by a professional carer, is undeniably poignant. And it's a curious end for a woman from a strict Methodist household who grew up without an indoor toilet – not because the family was poor, but because her father wouldn't countenance such luxuries. In that sense, her death is a symbol of the contradiction at the heart of her character, which undermined the self-proclaimed simplicity of her politics.

As a girl, Margaret Roberts was clever but not intellectual. Her mother was a nonentity in Margaret's eyes, omitted from her Who's Who entry, while her father, a lay preacher and alderman, meant everything to her. "He taught me that you first sort out what you believe in. You then apply it. You don't compromise on things that matter," she said. This identification with the dominant male is the key to her personality, explaining why many have found it hard to recognise her as a woman.

To be precise, the struggle is to identity her as a modern woman. The name by which she was known – "Mrs" Thatcher – belongs to an earlier age, and her appearance drew on a formality already in decline by the 1960s. Yet at first glance she was a pioneer in many ways. In 1952, when she was looking for a safe seat, she made "trenchant demands" – so says Hugo Young's biography – in a newspaper article about the need for more women in Parliament. Of course, she did so from the standpoint of a graduate with a wealthy husband who bankrolled her ambitions. "The battle for women's rights has largely been won," she said in 1982. "I hate those strident tones we hear from some women's libbers."

She meant her own battle. Not for the first time, Thatcher was conflating her own experience with that of people whose circumstances were a great deal less privileged. Another species of cognitive dissonance surfaced after her election victory in 1979, when she talked about bringing harmony, faith and hope to the country. In no time at all she had plunged into fights to the death over the Falklands and with the miners, and it now seems that the truest thing she said that day was about faith. In an increasingly secular age, she had the single-minded certainty of the believer, expressed in a Manichean formula: "I am in politics because of the conflict between good and evil, and I believe that in the end good will triumph."

In our complex world, it sounds like the blurb from a computer game, but Thatcher's values were Edwardian; while two of the three current party leaders are atheists, it's another measure of how distant the former prime minister appears from contemporary mores. Later, she returned to traditional language about the importance of marriage and motherhood, ignoring the fact that she had a live-in nanny and then sent her children to boarding school.

Like a lot of right-wing women, Thatcher preferred being with men but she appeared to them in different guises. "In her presence you pretty quickly forget that she's a woman," said Jimmy Carter's national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski. She may have toned down her version of refined femininity with Americans, but in a political party where maternal deprivation was common, she adopted the persona of the only powerful female figure in a boys' school – matron. It made her not so much a mother as a mother substitute, which is why many of the anecdotes about her have an under- current of squirming adolescent eroticism. But it was fatal in other respects, setting her apart from other women and confirming her indifference to gender equality.

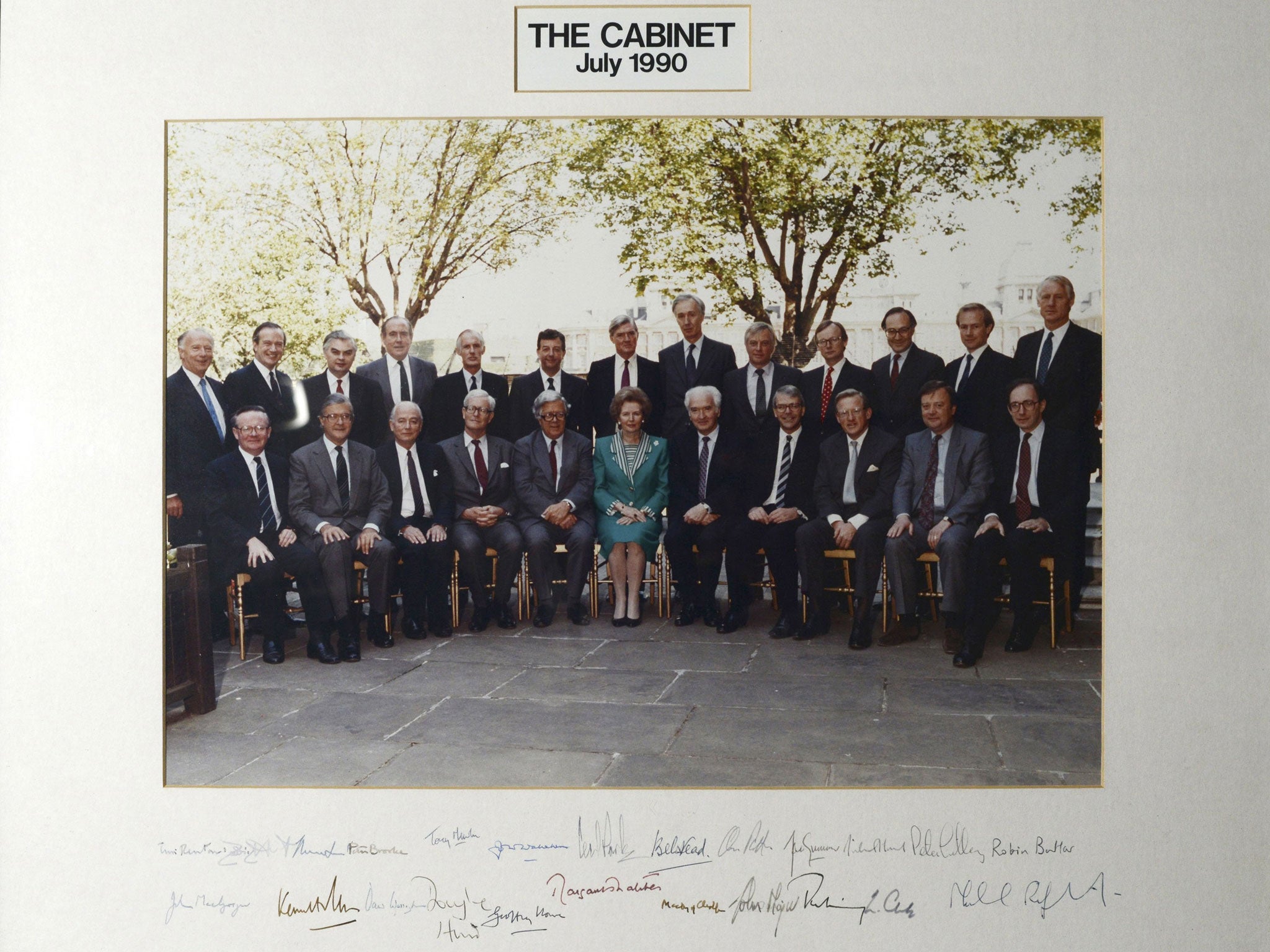

Almost a quarter of a century after she left office, her legacy to the Conservative Party has been five male leaders in a row. A different kind of politician could have done a great deal for other Tory women, mentoring them and helping them into safe seats, but Thatcher had neither the will nor the imagination.

The most serious charge against her is that she put her father's stern principles into practice for other people, not herself. Perhaps she wondered why other elderly widows didn't just move into a suite at the Ritz. But the embrace of traditional male values which made her palatable to Conservative grandees didn't help her in the end. She was never "one of them" and they were ruthless when they decided to get rid of her. As her funeral approaches, the question that Britain's first female prime minister leaves behind is not whether a woman can get to the top. It's how she could do it and yet have so little positive effect on the lives of other women.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments