Look to melancholy, not psychosis, for the real source of British comedy

In order to get closer to the real affinity between joking and moping, it might be wise to abandon the diagnostic categories beloved of psychiatrists

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

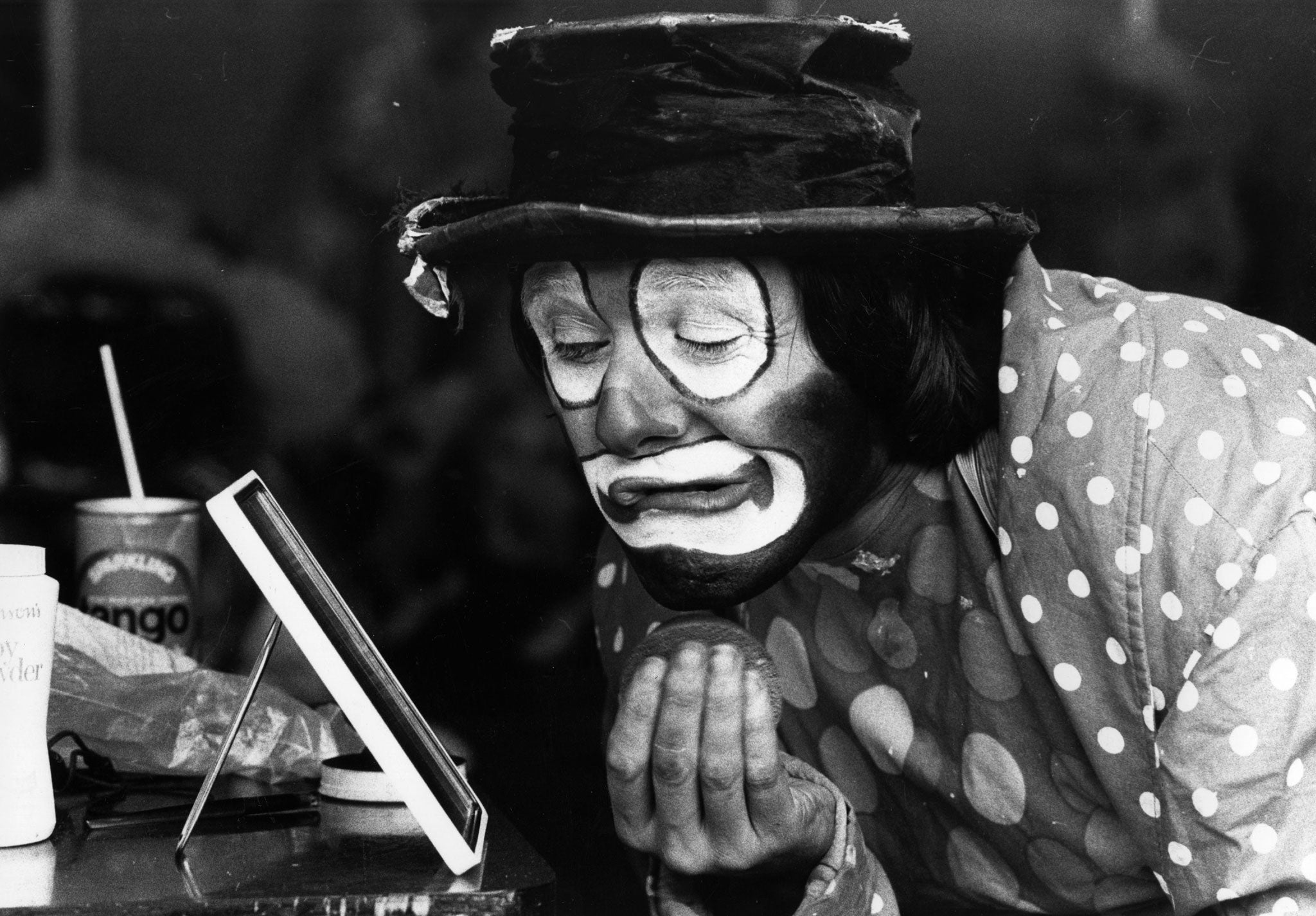

Your support makes all the difference.A wealthy and successful man goes to see a doctor. “Doctor, I’m depressed,” he complains. “I have money, respect, celebrity. Many people love me. But nothing can lift my spirits.” “I know what will help you,” the medic replies. “Go and see the clown Grock. He’s hilarious. He’ll have you in stitches in no time. That Grock, he could make a corpse cackle.” “But doctor, you see – I am Grock.”

The most interesting thing about that grime-encrusted anecdote is that attaches itself over the ages to different lords of laughter. For all his attacks of the blues, the Swiss circus and variety star Grock had by the 1920s managed to build himself a 50-room villa on the Italian Riviera. But more than century earlier, a similar tale was told about Joseph Grimaldi, who amassed – and then squandered – huge fortunes as the unrivalled principal comedian at Drury Lane, Sadler’s Wells and other London theatres. Bouts of depression, breakdown and despair – deepened by drink and debt – hounded Grimaldi (the original “Joey”) until his premature death in 1837. After the wastrel son of his second marriage predeceased them, he and his wife agreed a suicide past. Tragically – comically – the poison completely failed. As he punned, “I make you laugh at night but I’m Grim-all-day.”

A poignant little park around the grave near his Islington home commemorates the first British comedy giant – and a man whose genius for making other people laugh seems to have brought him little sustained happiness.

“Here we are again!” Grimaldi used to say as he bounded on stage in Aladdin, Cinderella, Mother Goose and the other pantomimes that he turned into perennials of popular culture. His catchphrase comes to mind in connection with this week’s academic study on the affinity between prowess in comedy and psychological disorders. The Sad Clown, a familiar fixture for centuries, now has to face down not only hecklers and drunks but beady-eyed clinicians scribbling in the stalls.

In a paper for the British Journal of Psychiatry, researchers from Oxford University and the Berkshire NHS Trust surveyed 523 comedians (119 women among them) and compared the results with groups of actors and non-performers. The moody gagsters reported unusually high levels of non-standard mental experiences (paranormal events and suchlike), disorganised thinking, absence of intimacy and impulsive behaviour. For Professor Gordon Claridge of Oxford, “the creative elements needed to produce humour are strikingly similar to those characterising the cognitive style of people with psychosis”.

It’s the way he tells them. As cautious as a greenhorn stand-up given a prime-time break by Michael McIntyre, Professor Claridge makes clear that his investigations indicate a correlation – “strikingly similar” – rather than causation. Psychosis does not generate comic talent. You might certainly detect a formal analogy between solo routines in which an apparent train wreck of stray insights and random ideas coheres thanks to lateral, associative logic and the thought patterns observed in some patients diagnosed with personality disorders. That, however, would never deliver a punchline, let alone a headline. And Professor Claridge chucks his previous caution to the winds when he goes on to describe comedy as “a kind of self-medication”. From the raw survey data alone, how does he know?

All the same, intuition, observation and history do suggest a link between mirth and misery. “And if I laugh at any mortal thing/ ’Tis that I may not weep,” wrote the wildly mood-swinging Lord Byron in Don Juan. Millions of viewers with no other knowledge of mental-health problems will have followed Ruby Wax through her depressions or Stephen Fry across his bipolar peaks and troughs. Russell Brand’s previous diagnoses – both a bipolar condition and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – are routinely wheeled out for our titillation.

Among previous generations of comic titans, Spike Milligan, Tony Hancock, Peter Cook and Kenneth Williams all struggled with black dogs and blue demons. Note their broad spectrum of suffering. Hancock committed suicide, via an overdose in Sydney in 1968, after he had fashioned the doggedly deluded everyman that Steve Coogan and Ricky Gervais would develop. The sad clowns of the postwar decades stretched in their plight from Williams’ obsessional self-control and solitude to the grandiose manic excess that seized hold of Milligan. As for the inspired Richard Pryor, that profane and profound spokesman for African-American pain and rage, his botched suicide attempt in 1980 led (shades of Grimaldi) to third-degree burns and priceless material for future gigs. Perhaps, to mangle Tolstoy, every unhappy funny man is unhappily funny in their own way.

As in most public discussions of the health of well-known figures, a reporting bias comes into play. Because we tend to know more about their state of mind than about Mrs Bloggs across the road, we presume that they endure more frequently an assortment of high-profile maladies. But that’s not necessarily the case. Study after study suggests that about one person in every four will experience some kind of challenge to their psychological well-being. Alan Bennett, whose own wit tends to merge unassuagable sadness with an equally sturdy sanity, has written tenderly about the crippling depressions of his mother, a Leeds butcher’s wife. In general, the obscure suffer in silence, away from any spotlight. “There is a snobbery about mental affliction beginning, I suspect, with Freud,” Bennett writes. “There was little twisting of the cloth cap went on in Freud’s consulting room.”

In order to get closer to the real affinity between joking and moping, it might be wise to abandon the diagnostic categories beloved of psychiatrists. After all, they change more rapidly than the novice acts on an open-mic night. Look at the 60-year history of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and you plunge into a tragicomic narrative. Over five editions, hubristic doctors have sought to medicalise every variety of human distress, or even just human diversity, for the greater profit of the drug companies. Homosexuality was listed as a pathology in DSM between 1952 and 1974; shyness (introversion as an alleged form of “autism”) would have appeared last year in DSM were it not for a rearguard action by outraged therapists.

As for the “bipolar” diagnosis now lazily associated with the comic’s art, it reflects the ever-fuzzier mental entities that boost the balance sheets of Big Pharma. Some patients with a syndrome that, in acute form, is no laughing matter still prefer the more expressive language of “manic depression”. In his recent polemic Strictly Bipolar, the psychoanalyst Darian Leader dissects the ballooning of this category into a catch-all label for any emotional oscillation. Anyone who has sought to help a sufferer through a severe manic-depressive (OK, “bipolar”) episode will know that such a terrifying descent into dread, delusion and panic has nothing in common with a comic’s merry free-associative patter.

It could be that students of comedy’s kinship with dejection have more to learn from old writers than from modern psychiatrists. They might even begin by looking again at the traditional diagnosis of “melancholy”. A pillar of ancient medical practice, the condition of melancholy became a fashionable obsession after the Renaissance. The English, in their land of damp fogs and cloudy ales, were thought especially prone to it.

But melancholy did not rule out humour. Quite the opposite: it sharpened dark wit of every kind. In 1621, the maverick scholar Robert Burton published his mammoth treatise on the subject, The Anatomy of Melancholy. As delighted readers have spotted ever since (it was a favourite book of both Samuel Johnson and John Keats), it’s a comic masterpiece. Burton’s digressive, overwrought broodings on melancholy through the ages amount to a gargantuan comic routine. “Humorous they are beyond all measure,” writes Burton of madmen, as if describing his own wayward style of verbal riffs. “Though they do talk with you, and seem to be otherwise employed, and to your thinking very intent and busy, still that toy runs in their mind, that fear, that suspicion, that abuse, that jealousy, that agony, that vexation, that cross, that castle in the air, that crotchet, that whimsy, that fiction, that pleasant waking dream, whatsoever it is.” The ultimate literary stand-up, Burton rambles, strays and speculates, loses his thread and then picks it up pages later. As he writes, “I have overshot myself.”

In the next century, Laurence Sterne shamelessly plundered Burton for his own supreme comic ramble of a novel, Tristram Shandy. “Writing, when properly managed … is but a different name for conversation,” he insists. And Shandy’s “conversation” mostly turns on failure – sexual, emotional, professional, even the author’s basic failure to stick to the point and progress his wandering plot. Almost 250 years after Shandy’s monologue, a couple of classic melancholy clowns claimed it for their own. In A Cock and Bull Story, directed by Michael Winterbottom, Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon acted as versions of their own comic personas as they sniped and bitched their way around a film version of Sterne’s novel.

English (or British) comic melancholy thrives, in figures such as Coogan’s Alan Partridge, Gervais’s David Brent or Brydon’s Uncle Bryn (Gavin & Stacey). Neither is that native sad hilarity a masculine preserve. You may pick up the same vibe behind the slapstick of Miranda Hart. She has spoken of her “default” pessimism and said that “I have to force myself every day to not do glass half-empty.” Comedy blooms on the rough ground of controlled, creative melancholia. If that is the disease, then who wants a cure?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments