Some of you may have missed this vitally important date in the cultural calendar, but it turns out that 9 October was "Super Thursday". An early warning shot in the 2016 US presidential election, perhaps? No, Super Thursday is traditionally – well, for the past decade or so – the day in early autumn on which, attended by maximal publicity and a henge of supermarket dump bins, the UK publishing industry unloads on to the marketplace the (potentially) best-selling items which, it is assumed, will keep the booksellers' tills in action and, alas, inflate the profits of messrs Amazon from now until Christmas.

And what sort of books made their presence felt in the Waterstones window displays on Super Thursday? The new Ian McEwan and the new Rachel Cusk? No, those came out last month, were respectfully reviewed, made much of in what Jimmy Porter in Look Back in Anger christened "the posh Sundays" and will have sold a few thousand copies to devotees. This weekend, alternatively, the shops are full of Roy Keane's latest collection of aimings and blamings, Stephen Fry's new autobiography, buxom novels of a kind that don't, generally, get noticed by the posh Sundays, works by celebrity chefs, sportspeople and pop stars.

Naturally, some of these will be well worth the massively discounted price charged for them – why, my own wife published a novel last Thursday. But in general terms – something most half-way intelligent publishers would readily concede – Super Thursday represents the high-water mark of what the Victorian critics, quite as exercised by questions of taste as the pundits of today, classified as biblia aliblia: books which, although comprised of paper, print and binding are not, by certain up-market definitions, books at all, and a part of whose profits are, or, a gloomier analyst would say were, intended to subsidise all those promising first novels by the hundreds of creative writing graduates who pour forth each year from the university system.

By chance, Super Thursday coincided with this year's Frankfurt Book Fair, a convention at which mighty deals are struck for the kind of novel in which, as Martin Amis once remarked, you can be pretty certain to find the phrase "Towards morning he took her again" and the book trade's future is nervously discussed. This year's prophecies, it turns out, are not quite so gloomy as once they were, for the increase in sales of ebooks, now at just under 25 per cent of the total, seems to be flattening out, while at least one or two of the tentacles of the giant monopolistic squid that is Amazon look as if they may be prised back.

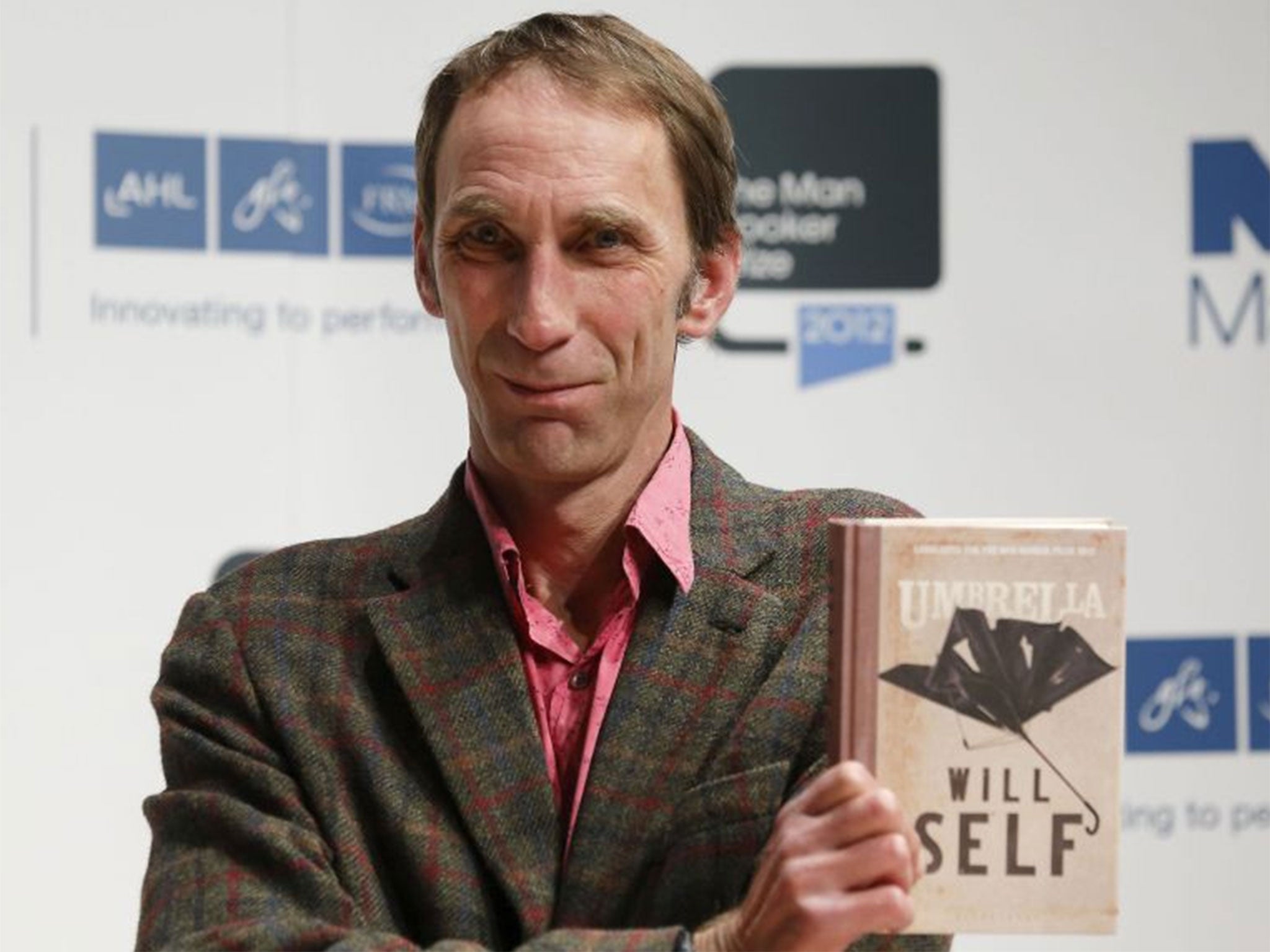

It also coincided with a terrific jeremiad in The Guardian courtesy of Will Self on the nature of modern literary culture, here defined as the whole environment in which books are conceived, published, brought to the market, reviewed, read and digested by the society they ornament. Self's provocative conclusion is that old-style literary culture is dead; that technology, or rather the way in which the modern consumer reacts to it, has fostered an atmosphere of instant gratification in which novelty conquers all, product is flung at us from all sides, the ability to discriminate is gone, the capacity to "deep read" in the way our ancestors managed this difficult act is vanishing and reduced attention spans will eventually displace anything remotely complex or nuanced from the agenda.

It was a splendid harangue, which anyone professionally enmired in the world of books will have approached with a twinge of recognition. For no one could doubt that the way in which people read and respond to the books placed before them is changing, and that "literary culture" is no longer the unshiftable monolith it once was. Yes, there are schoolchildren who have difficulty with a work longer than 200 pages – it was to Michael Gove's credit that he determined to do something about this. Yes, the free-for-all of the Amazon forums seems almost designed to encourage mass exaltation of the second-rate, and yes, the shortage of space in newspapers has prompted a flight to what Julie Burchill once called the "love it or shove it" approach to criticism in which books are either piped ceremoniously on board or thrown into the depths, with precious little room for nuance.

At the same time, the Self thesis, while bound to depress anyone who thinks that the average teenager would be better off reading Dombey and Son than playing on an Xbox, turns slightly less cataclysmic when seen in the context of a couple of centuries' worth of literary history, for it assumes that the entity known to cultural historians as "the reading public" has always been driven by the same sets of rules and aspirations and been based on the same level of comprehension. In fact, from a very early stage in its existence the reading public has been as diverse and as multi-layered and as suspicious of, or detached from those contending layers as, say, the audience for football or the congregations of church services.

Its early 19th-century version, back in an age of mass illiteracy and widespread distrust of such a secular art form as the novel, was absurdly small by modern standards: Vanity Fair, for example, sold no more than 10,000 copies in its author's lifetime. But within half a century the Victorian educational reforms and developments in the newspaper and magazine publishing industry had created not only a vast new body of readers but a culture in which, uniquely, reading was the dominant pastime. As the historian Philip Waller puts it in his magisterial survey Writers, Readers and Reputations: Literary Life in Britain 1870-1914: "The late-Victorian period ushered in an unprecedented phenomenon, a mass reading public. We may now want to add that this was both the first and the only mass reading public."

Come the 1920s, on the other hand, all this universality – a world in which James Joyce and Joseph Conrad could end up submitting material to the mass-circulation weekly Tit-Bits - had gone. The first signs of a decline in library borrowings, ripe to be reduced by the attractions of radio and cinema, were detected even before the First World War. And far from being homogeneous, the readers who remained were engaged in pitiless "taste wars", with highbrows sneering at popular novelists and popular novelists returning the compliment by finding Virginia Woolf's novels "difficult" or The Waste Land a deliberate attempt on Eliot's part to exclude ordinary people from the enjoyment of poetry.

For almost a century, in fact, the audience for books has been steadily fragmenting, less able to arrive at a collective judgement, less confident that what used to be known as "taste" – that is, "good taste", meaning the set of superior cultural preferences on which the smart money used to be placed – even exists. Undoubtedly, developments in technology and marketing will continue to nag away at the old ideal model of literary consumption, but you sometimes suspect that this model never really existed in the first place.

Readers, as most novelists eventually discover to their surprise, have a habit of responding to books in highly unusual and individual ways, of confounding the expectations the publishing industry has of them. And while a glance around cyberspace this weekend, with its piles of discounted rubbish and its excited tweets about books that will be forgotten in a week's time, might suggest that old-style literary culture is dead, it seems likely that the old-style reader – the "proper reader", for whom a book is not just a cultural condiment, but a vital accessory for life – will narrowly survive.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments