Like all good space films, ‘Rosetta’ has us hooked

Annually, the agency’s operations cost “about the same as the price of a cinema ticket” for each citizen of the 20 participating nations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

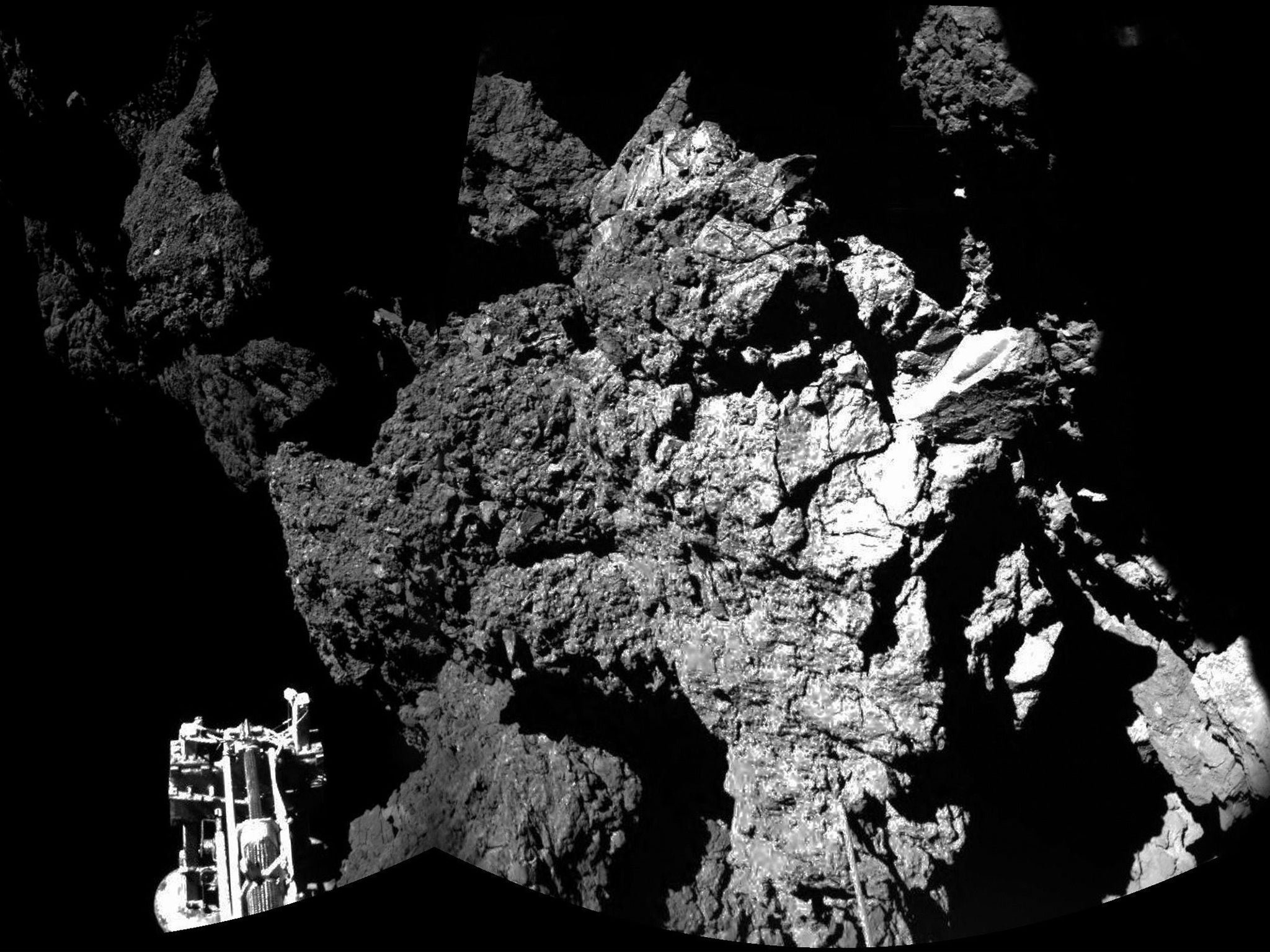

Your support makes all the difference.How much has it cost the taxpayers of Europe to send the Rosetta mission on its decade-long journey towards Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and plant the Philae lander – after a bounce or two – on its surface? Ask the European Space Agency (ESA), and you get a telling answer. Annually, the agency’s operations cost “about the same as the price of a cinema ticket” for each citizen of the 20 participating nations. Popcorn bucket and supersized cola not included.

In which case, the ESA has screened a crowd-pleasing blockbuster this week. Only 10 days after the crash of Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo in the Mojave Desert, European public-sector science has boldly gone not just far out on Rosetta’s 6.4bn-km voyage – but far back to a time when hope and excitement flew out on every hi-tech trip towards the final frontier. A fortnight before (on 28 November) Stanley Kubrick’s mystical and speculative masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey returns to British cinemas in a spanking new digital transfer, that frontier pulses again with the thrill of revelation.

“Origin is the goal,” wrote Viennese satirist Karl Kraus – an apocalyptic wit who, after the First World War, had near-zero faith in progress of any kind. Yet Kraus’s idea docks neatly with Rosetta. The project deploys leading-edge research and technology in order to investigate the distant sources of life on Earth. Why “Rosetta”? Because, explains the ESA, Jean-François Champollion’s decryption of the Egyptian stone “provided the key to an ancient civilisation”.

Now, the double act of orbiter and lander may allow scientists “to unlock the mysteries of the oldest building blocks of our solar system”: comets. So astrophysics fuses with a kind of planetary archaeology – or ultimate genealogy. The science of the future excavates our deepest past. For ESA, comets could have delivered “the complex organic molecules that may have played a crucial role in the evolution of life on Earth”. At which point, many people of a certain age – sober scientists among them – will start to think about some crushed or powdered version of Kubrick and Arthur C Clarke’s enigmatic monoliths.

For its eager followers as well as its proud architects, Rosetta has set a course into the past. Whatever discoveries lie in the offing (next year, an Indian mission will aim for Venus), a penumbra of nostalgia now surrounds space exploration. Kubrick’s film came out in 1968, just before the Apollo 7 astronauts Wally Schirra, Walt Cunningham and Donn Eisele first broadcast live from space. The cosmic revolution would be televised. John F Kennedy’s plan to trounce the Soviets and put a man on the moon by 1970 fused with a new golden age of science fiction to generate an atmosphere of febrile futurism. Like 2001 itself, that could feel utopian and dystopian at once.

Overall, the dreamers outnumbered the doubters. Exactly 24 men travelled to the Moon; 12 walked on its surface between 1969 and 1972. Eight moonwalkers survive; the youngest is now 79. But Alan Shepard, commander of Apollo 14, was already 47 when he reached the lunar surface. He had served in the Pacific during the Second World War. The zenith of space fever can now seem far way, and long ago.

At the time, it paradoxically united a costly Cold War strategy (with its roots in the experimental rocketry of the Third Reich) and a New Age mindset made up of planetary self-consciousness and inter-galactic reverie. Star Trek, apart from 2001 the sturdiest and subtlest cultural monument to that epoch, first aired in September 1966. With Apollo 17, six years later, a final human mission brought the military and mystical sides of space culture together in one immortal image. Taken in December 1972, the “Blue Marble” photograph of the Earth seen from 45,000km away has seen service as an inspirational logo for a host of green campaigns.

In part because of the Vietnam War, in part because its Soviet rivals refused to play on the terrain of manned flights, Nasa’s heyday quickly passed. During the later 1970s, inter-planetary dreams waned along with post-war techno-optimism that had induced them. For decades, Nasa has published a magazine – now website – called Spinoff. It records the everyday benefits that space research has brought us, from medical LEDs and lightweight “space blankets” to freeze-dried food. However, it turns out that the two useful substances people think originated with the space programme – Teflon and Velcro – did not. Both predate Nasa.

Yet tougher radial tyres and cordless tools (two further spin-offs) will hardly transport us into a new dimension. Did humans stroll on our silver satellite and show us our fragile blue home just for the Dustbuster (not that I’m knocking flex-free vacuuming)? That gnawing hunger to escape the pull of Earth – an astrophysical take on the aesthetics of the Sublime – persisted. Shuttles, stations and missions to Mars and beyond have periodically slaked it. The feel-good frenzy that Rosetta has aroused hints that millions still share that appetite for transcendence. With its intellectual horizons stretching across time as well as space, ESA’s probe has scratched that itch. Even if Philae fails to come out of its tight spot on 67P, we can all party like it’s 1969.

Objections to space missions on the grounds of waste or risk always run up against this expeditionary gene. True, nationalism has played its part as well, first for the Cold War superpowers and then with India and China – although, in India’s case, its home-developed rockets often carry other countries’ satellites into orbit, free of charge. As for regional self-regard, this week Europe at last did something complicated (almost) right: a theme more explicit in the continental media than in the UK. Above all, though, the jubilation and curiosity ignited by Rosetta hark back to a more robustly progressive age.

That 1960s optimism did not stop with technology. It also extended to boundary-breaking education. Aptly enough, one of the 10 investigative devices aboard the Philae lander is Ptolemy: a gas analyser designed and developed at the Open University. Led by the late, unforgettable Colin Pillinger (one of the pioneers of Ptolemy), the emergence of the OU as a world-ranking centre for space science happily dovetails the visionary and democratic impulses of the High Sixties. Pillinger had his own pop-cultural passions. He enlisted both Blur and Damien Hirst as participants in his ill-fated Mars lander, Beagle 2, in 2003. Even so, we have to assume that the striking resemblance of the miniature ovens of Ptolemy to the self-propelling stove discovered on the Moon in Wallace and Gromit’s A Grand Day Out is largely coincidental.

Even without claymation, the popular arts and high-end astrophysics keep up their dance of mutual seduction. Far from being shy wallflowers, scientists can take the lead. Theoretical physicist Kip Thorne advised director Christopher Nolan on his new space epic, Interstellar, and has a credit as co-producer. For Thorne, the aim is that “science is embedded in the fabric from the beginning”.

Yet the downbeat, post-catastrophe mood of Interstellar suggests that deep space has become a markedly less cheerful location since the Sixties: from adventure to Armageddon. In keeping with the muzzled aggression of the Cold War, the ruling metaphor of cosmological exploration used to be conquest. Later it morphed into the humbler idea of contact – if not with those annoyingly taciturn alien civilisations, then at least with the strange phenomena that fill in the backstory of the universe. And of ourselves.

Back on 67P, Ptolemy has a front-line role in the testing of the “stardust” theory. Once heretical, the notion that life in molecular form might have arrived from outer space moved into the mainstream. In the 1960s, the proposition began to interest Charles Townes – not an astronomer, but a physicist who had won a Nobel Prize for the groundwork that led to lasers. The top astronomer at Berkeley, Townes’s university, told the maverick that it was possible to prove the dry sterility of interstellar space. Undaunted, Townes and his collaborators turned his own techniques of microwave spectroscopy towards the beyond. Eventually, they found water molecules in the Orion Nebula. No longer the arid desert of the 1950s, the universe now looks damper than a Manchester autumn.

Townes – still with us, aged 99 – first located ammonia molecules in a gas cloud in 1968. Someone was paying attention. Less than a month after Neil Armstrong made his giant lunar leap in July 1969, the Woodstock festival took place in upstate New York. Joni Mitchell did not attend, but heard all about that baptismal rite of the Age of Aquarius from her then partner, Graham Nash. The next year, her song “Woodstock” informed the burgeoning counter-culture that “We are stardust/ Billion-year-old carbon… And we’ve got to get ourselves/ Back to the garden”.

Just now, that paradisal garden takes the form of a twin-lobed icy grit-ball hurtling around the Sun 500m km from Earth. As for Philae itself, every space opera needs a suspenseful twist. The plucky little lander sits wedged in a hollow against a wall or boulder. Will its drills gather enough samples of potential “stardust” before the batteries die? Whatever its fate, ESA’s retro cliffhanger has already justified the price of that ticket.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments