Lee Halpin's tragic story shows the terrible plight of the homeless - but does anybody care?

We are slyly slipping back from the caring society that founded Crisis and Shelter to one holding Victorian attitudes to work, poverty and misfortune

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The interminable winter is making millions of us depressed and ill. Every artery and bone feels frozen and slow. Some days, even with the heating on, our flat doesn’t warm up enough and so, like so many other Britons, I hug hot water bottles and drink too much tea. In an ordinary winter, deaths in the UK rise because of illnesses either brought on or made worse by cold temperatures. The mortality figures here are higher than in Russia with its truly savage climate. Now think of the homeless men and women sleeping rough. How do they survive when the temperature dives to between zero and 4C? Many don’t. They die, nameless and missed only by the few who shared their pain. We don’t even have proper numbers for these unknown dead. Where are they buried?

Right opposite Harrods last Saturday, an old woman sat on the pavement moaning for money. In her many tattered layers and hoods, she looked like a big, swaddled baby. Click, click, click went the heels around her. Louis Vuitton and Harvey Nichols bags swept past her face and nobody could be bothered to stop, take out a coin, bend down and hand it to her. By now someone will have swept her off that space – such an eyesore for tourists.

As a nation we used to talk about those who were dispossessed. Shelter, Centrepoint and Crisis campaigned to a relatively receptive population. Princess Diana did much to highlight this blot on our landscape. But when she died, concern seemed to die too. Those without places to live include the itinerants on our streets and others we don’t see – families living in temporary accommodation and in hostels.

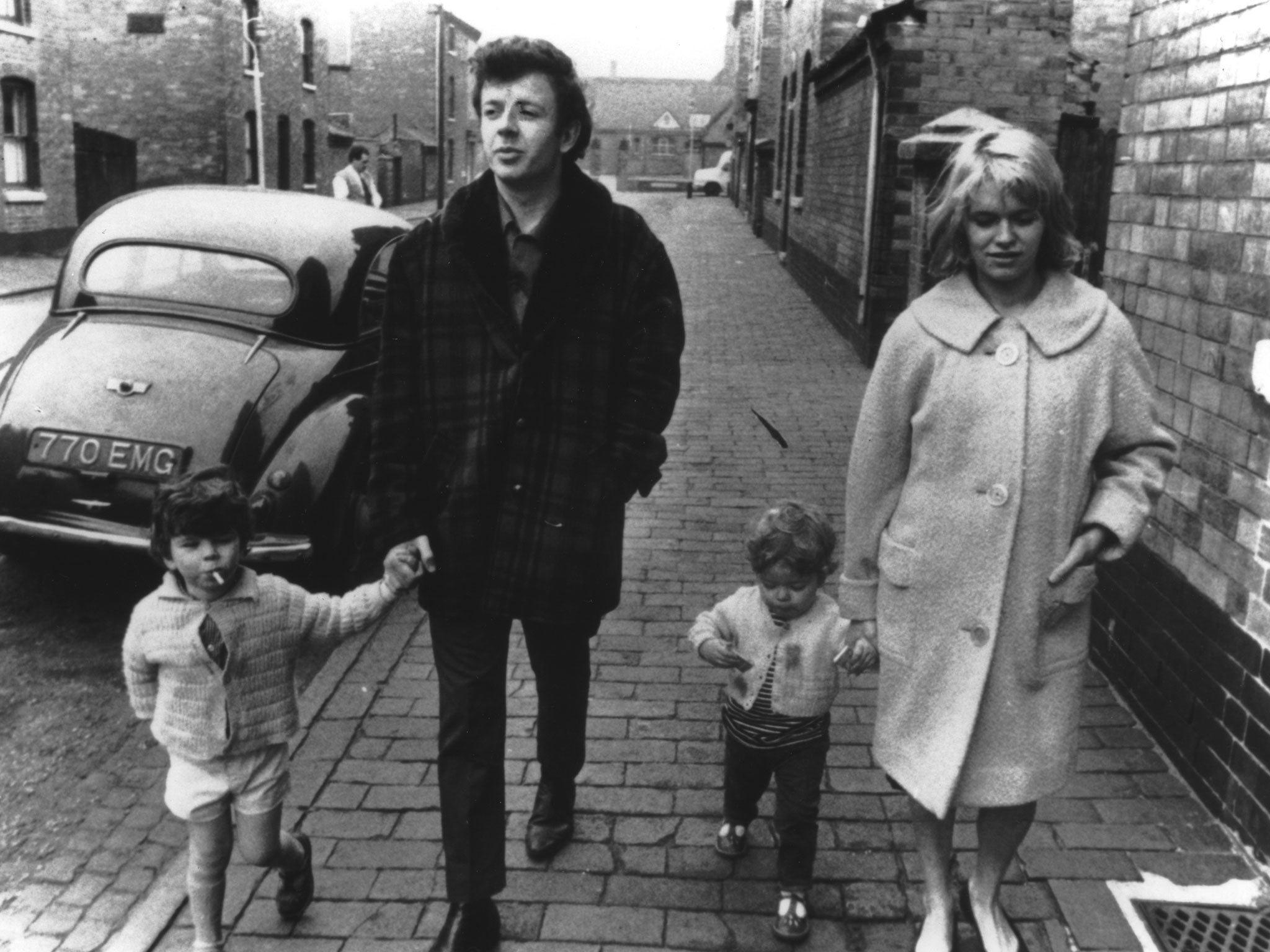

I worked for Shelter once, then a chic charity supported by rock stars and fashionistas, which allowed it to extend its good work, helping those hit by the storms of life and without a roof over their heads. As part of my training, I was shown Cathy Come Home, the devastating BBC play, broadcast in November 1966, written by Jeremy Sandford and directed by Ken Loach. The story is of a young couple, Cathy and Reg, happy and in love with each other and their baby. After being injured, Reg is sacked by his employers and their lives crash. When they are evicted and unable to afford another home, they are turned into a “social burden”. Their child is taken into care, the cruellest, final cut.

At the time the film was debated in Parliament, it aroused the nation’s conscience and it led to the setting up of Crisis and Shelter. Now we are slyly slipping back from that caring society to one holding Victorian attitudes to work, poverty and misfortune. Today’s employers once again hire and fire at will; welfare is considered shameful for those who need it; we are told the destitute have made “lifestyle choices” to subsist and cling on to life, and, worst of all, there is no official acknowledgement of the structural reasons for homelessness.

Shelter warns that every 15 minutes a family finds themselves homeless or perilously close to it. Crisis is equally worried about the rootless, roaming, impoverished families it sees. The charity rightly says a home is not only a physical place of security, but contributes to one’s identity, one’s sense of being human.

Official local authority figures show that homelessness fell significantly between 2004 and 2009. Then, in 2010, the numbers started going up again. According to the non-political data analyst SSentif Intelligence, between then and 2012 there was a 25 per cent increase in people needing places to stay and a significant drop in funding to meet that need.

In Birmingham, for example, the response to this steep rise in homelessness was a cut of 29 per cent in spending on these people, many of them children. Increasingly, once employed middle-class individuals are finding themselves in this position, not because they think it’s cool but because they were laid off in the recession. The Yorkshire Post recently ran the story of Jason, a retail manager who lost his job, was thrown out by his partner and ended up on the streets. I have seen families with infants living in B&Bs in conditions we would not accept for dogs. There was damp on every wall, the windows and toilets were broken, and yet the landlords were charging good money for them.

Urban rats live better than these poor folk, stripped of all hope and dignity. But, unfortunately for them, they have no RSPCA to come and rescue them. Our nation indulges a spoilt, rich Royal Family, keeps a vast army, wants to spend many billions to replace the Trident nuclear deterrent, hands tax cuts to the richest even during the downturn, but won’t look after the most wretched on its land, 220,000 of whom are children.

The changes that came in early April will create yet more homelessness as people can’t pay their mortgages or their high, private-sector rents. Lee Halpin, a radio presenter and filmmaker from Newcastle, was trying to document the plight of these people by living for a week as they have to. After just three days of sleeping rough and scrounging for food, he was found dead, apparently of hypothermia. His story could have been our Cathy Come Home. But it raised barely a breeze of concern. Hard times have really and truly ossified our hearts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments