Larkin has secured his place in Poets’ Corner, and about time too

Larkin is a difficult human being to admire, but his poems are not

It’s quite the thing these days, to decide on the Nation’s Favourite. Presumably because the accolade gives authority to familiarity. There is a TV documentary series choosing the Nation’s Favourite Pop Song (Abba, the Bee Gees, etc) and we now know the Nation’s Favourite Bird is the robin.

But the Nation’s Favourite Poet? The Poet Laureate is something of a yardstick, but that is more about informed selection than majority vote. It is something of a relief, then, to learn that Philip Larkin is at last to be acknowledged by Westminster Abbey with a stone in Poets’ Corner because he, above all British post-War poets, is surely the Nation’s Favourite.

Speaking yesterday in Larkin’s old office at the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull (Larkin was university librarian there for 30 years), the Dean of Westminster Abbey explained that the hiatus between Larkin’s death in 1985 and the arrival of a memorial stone was because of a predecessor’s anxiety to “wait until a reputation was secure”. He continued by reading an excerpt from Alan Bennett’s diary that slightly shot a hole in this theory.

Writing somewhat grumpily (four years ago) after Ted Hughes got his stony spot at Westminster, Bennett questions why Larkin was, as yet, still unmemorialised. After all, he observed, “many more of Larkin’s writings have passed into the national memory”.

The National Memory. What an intriguing notion, but quite a good litmus test of who should get the Abbey gig. If you were to line up 100 people in your nearest high street and ask them to quote a couple of lines from a Ted Hughes poem, I suspect very strongly that you would be met by blank faces. Great poet and all that. GCSE fodder. Zero position in the National Memory. Whereas Larkin? With his rudely perceptive comments on parenting, his accuracy about sexual relations, Lady Chatterley and the rest – and above all, his acknowledgment of love’s durability? Larkin easily commands the day.

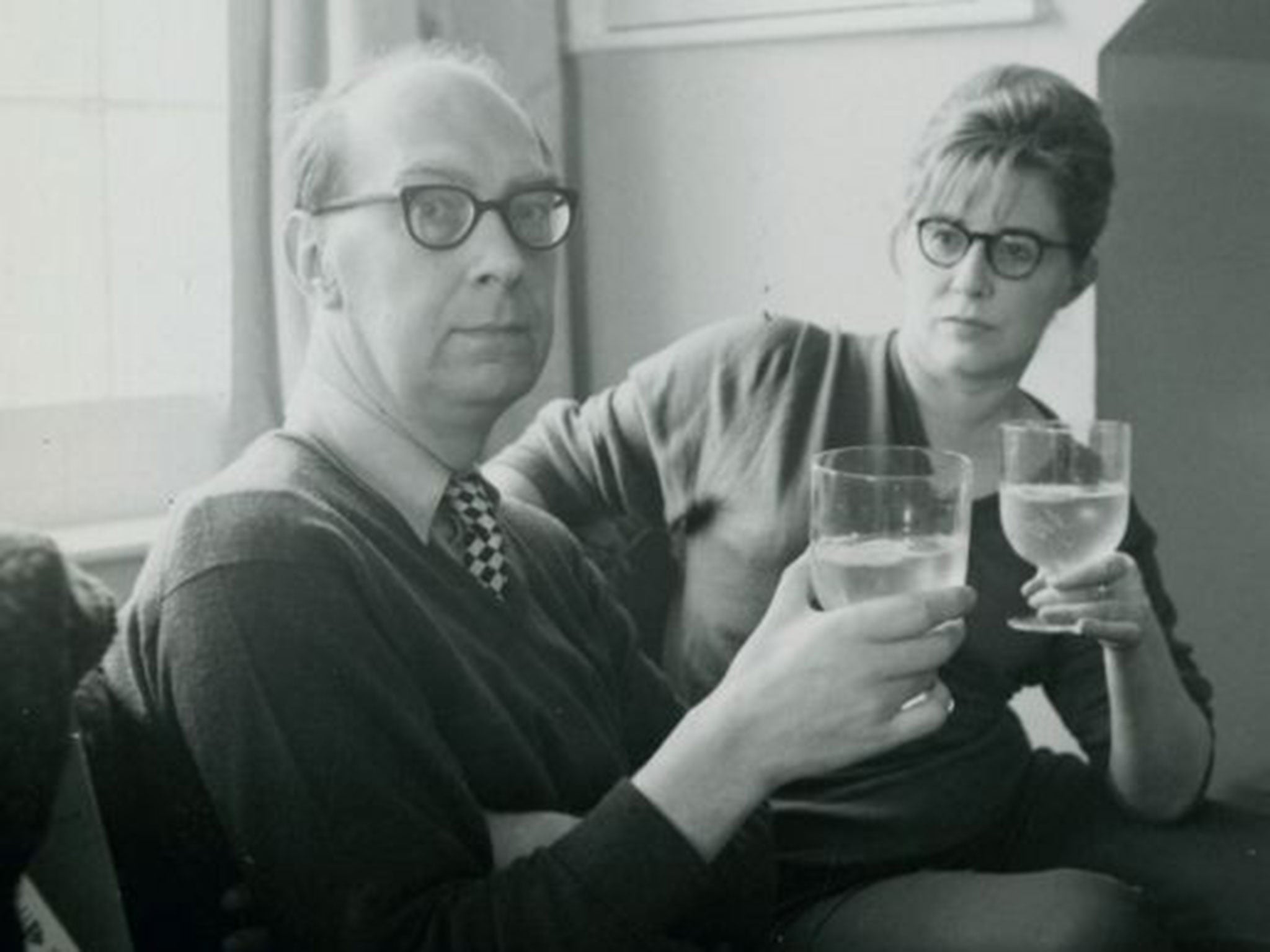

It’s the combination of rhyme, popular culture, and what some might call an Eeyorish sensibility that has endowed Larkin’s work with an almost unshakeable place in the National Memory. In spite of everything. The awkward biographical details, the casual racism revealed by the letters, the uneasy sexual relations (basically, loads of mistresses), and the fact that Larkin is, quite frankly, a difficult human being to admire. But the poems are not.

And this is Poets’ Corner. There is a reason why poems end up residing in the National Memory. It’s because they have been found to say something that is important, and true, and meaningful, and something that contributes to human understanding.

As his biographer (and former Poet Laureate) Andrew Motion has pointed out, his work is often “beautiful and true, and very often unforgettable as a result”. And so of the thousands of people walking through the Abbey, quite a number will soon go to Poets’ Corner to seek Larkin’s stone. And when they see it, their hearts will leap. Will they leap in a different way to the leap they may feel by seeing (say) the recently installed stone to David Frost? No offence to Frosty, but probably, yes. He has his place in the National Memory bank too, but in a slightly different aisle.

I must declare an interest here. As chair of Hull City of Culture, which thunders into the city in 2017, I have stood up many times and introduced a promotional film that kicks off with Sir Tom Courtenay heart-stoppingly reciting Larkin. I have read and re-read the poems and see how brilliantly and sensitively they depict the city, its buildings, its rivers and bridges.

In Hull’s Paragon Station there is a giant statue of Larkin running to catch a train, leaving lines of his poems engraved on the forecourt behind him. He always suggested he worked and lived in Hull because he wanted to escape, and the easternmost corner of Yorkshire seemed like a good place to do that. But the city became something of a muse to him, its unorthodox nature perhaps appealing to his innate anti-establishment zeal (he shunned both the Laureateship and an academic post at Oxford), its rivers, domes and big skies inspiring him to write his best work.

When people find out why I have become a regular commuter to Hull, they immediately tell me how much they love the work of Philip Larkin. Grayson Perry confided in me that Larkin’s Collected Poems has a permanent spot on his bedside table. Yesterday as the news spread that Larkin was to be memorialised in the Abbey (the Nation’s Favourite Gothic Church, perhaps), #larkin started trending on Twitter. The stone will be unveiled in 2016. The Dean says that if there is a line from the poems on the stone, there should be no question of which one it ought to be. No, not the rude one. As if! Surely “What will survive of us is love.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks