Keep the champagne on ice – there are some clear and worrying signs that the economy is slowing

Could a surprise drop in manufacturing output have wider implications?

This may be as good as it gets. Last week was full of downside economic surprises. It started with a data release by the German Federal Statistical Office showing that industrial production unexpectedly fell in real terms.

Adjusted for seasonal fluctuations and working-day variations, output was down by 1.8 per cent in May. That was well below expectations of a flat reading. Germany’s economy grew by 0.8 per cent in the first quarter and 2.2 per cent over the past year, but it now seems likely that Germany will see a slowdown in the second quarter. A slowing Germany is not good for either the eurozone or the UK.

Later in the week the ONS published the equivalent data for industrial production for the UK, which also took the market by surprise with its sharpest fall in 16 months. Total production in the UK decreased by 0.7 per cent between April and May. Manufacturing was the largest contributor, decreasing by 1.3 per cent. That compares with economists’ forecasts of a 0.4 per cent month-on-month gain.

Excuses such as “the series is volatile and will get revised upwards” were bandied about by those who called it wrong, despite the fact that average monthly revisions since 1998 are zero and since 2008 minus 0.1 per cent. Former Bank of England economist Rob Wood, now chief economist at Berenberg, even went as far as to say: “The surprise drop in UK manufacturing output in May is unlikely to be a true reflection of what is happening in the sector.” Actually, it probably is.

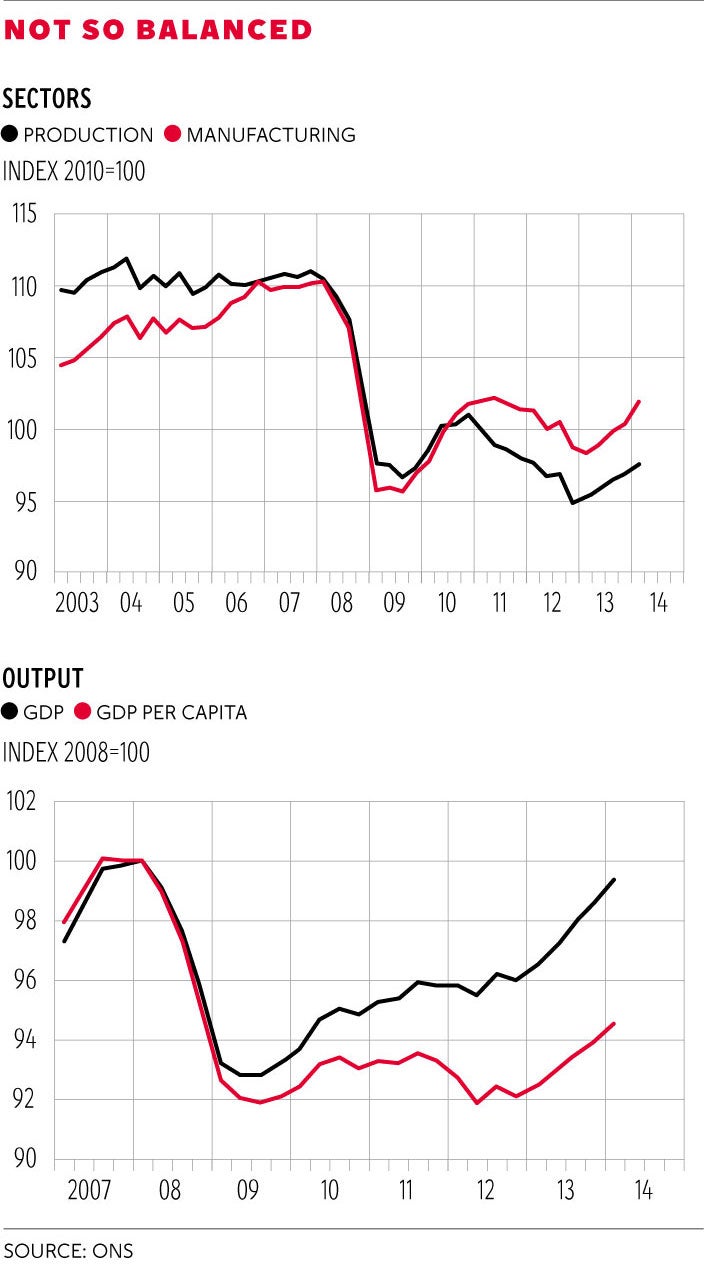

As the chart (below) makes clear, in the three months to May 2014, production and manufacturing were 11.3 per cent and 7.2 per cent, respectively, below their figures reached in the pre-downturn GDP peak in Q1 2008. In the United States manufacturing output is now just 2.6 per cent below its pre-downturn peak. UK industrial production is down 2.7 per cent since the Coalition took office in 2010 while manufacturing output is up just 2.2 per cent in total, or about 0.1 per cent a quarter.

Consistent with the slowing industrial production data, the British Chamber of Commerce’s (BCC) quarterly survey of nearly 7,000 companies showed most of its key measures for manufacturing and services companies fell in the second quarter of 2014. For both manufacturing and services, most of the BCC’s key balances fell in Q2 following the unusually strong Q1 figures. It should be said though, that all remain at historically high levels.

In particular there was a fall in export balances in both sectors in Q2, which suggests that the recent rise in the value of the pound – the equivalent of policy tightening – is beginning to bite. The manufacturing balance for export sales dropped from plus-40 per cent in Q1 to plus-30 per cent in Q2, the worst level since Q2 2013. The manufacturing balance for export orders fell from plus-35 per cent in Q1 to plus-31 per cent in Q2. The service balance for export sales dropped by nine points in Q2, to plus-29 per cent, the worst level since Q4 2012. The service export orders balance fell by seven points in Q2 to plus-30 per cent, the worst level since Q3 2013. A weak euro area in general and a slowing Germany in particular are likely to continue to adversely impact UK exports and hence hurt growth.

All the BCC’s national investment balances recorded falls in both sectors in Q2. The forward-looking employment expectations balances also fell for both sectors. The manufacturing employment balance fell one point to plus-30 per cent, the lowest since Q2 2013. The manufacturing employment expectations balance dropped nine points to plus-31 per cent. The service employment expectations balance fell three points, to minus-26 per cent.

The quarterly national accounts indicate that the UK economy grew at an unrevised rate of 0.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2014. GDP was around 3 per cent higher in the first three months of 2014 than in the same period a year ago, the highest annual rate of growth since 2007. GDP is up a total of 5 per cent since the Coalition took office in Q2 2010. The UK economy has now grown for five consecutive quarters: the longest run of sustained output growth since the onset of the economic downturn in 2008. As a result, output in Q1 2014 is just 0.6 per cent below the pre-downturn peak.

The National Institute for Economic and Social Research estimates suggest that output grew by 0.9 per cent in Q2 2014, which would mean that all of the lost output has now been restored, six years since the Great Recession started.

Now for the really good news. While much of the growth since the end of the economic downturn has been as a result of growing household expenditure, at long last investment growth has made a more substantial contribution in recent quarters. Investment reduced GDP growth by 0.1 percentage points in 2012 and added just 0.2 percentage points during 2013. Following contributions to annual GDP growth of 1 and 0.9 percentage points in Q3 and Q4 2013, respectively, investment added 1.4 percentage points to annual growth in Q1 2014: a similar contribution to that of household expenditure over the same period. Business investment grew by 10.6 per cent in the year to Q1 2014 and has now expanded for five consecutive quarters: the longest run of business investment growth since the onset of the economic downturn.

But we shouldn’t get too carried away. The second chart also highlights the path of GDP per capita – an indicator of output that controls for population changes. On this measure, the UK economy has also grown more quickly in recent quarters, albeit from a lower starting point. GDP per head has recovered relatively slowly since 2009 and is still 5.6 per cent below its pre-downturn level in Q1 2014, at around the level first achieved in mid-2005. It has grown by 2.2 per cent, or by a further pitiful 0.1 per cent a quarter, since the Coalition took office in Q2 2010. Time to break out the champagne? I don’t think so.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks