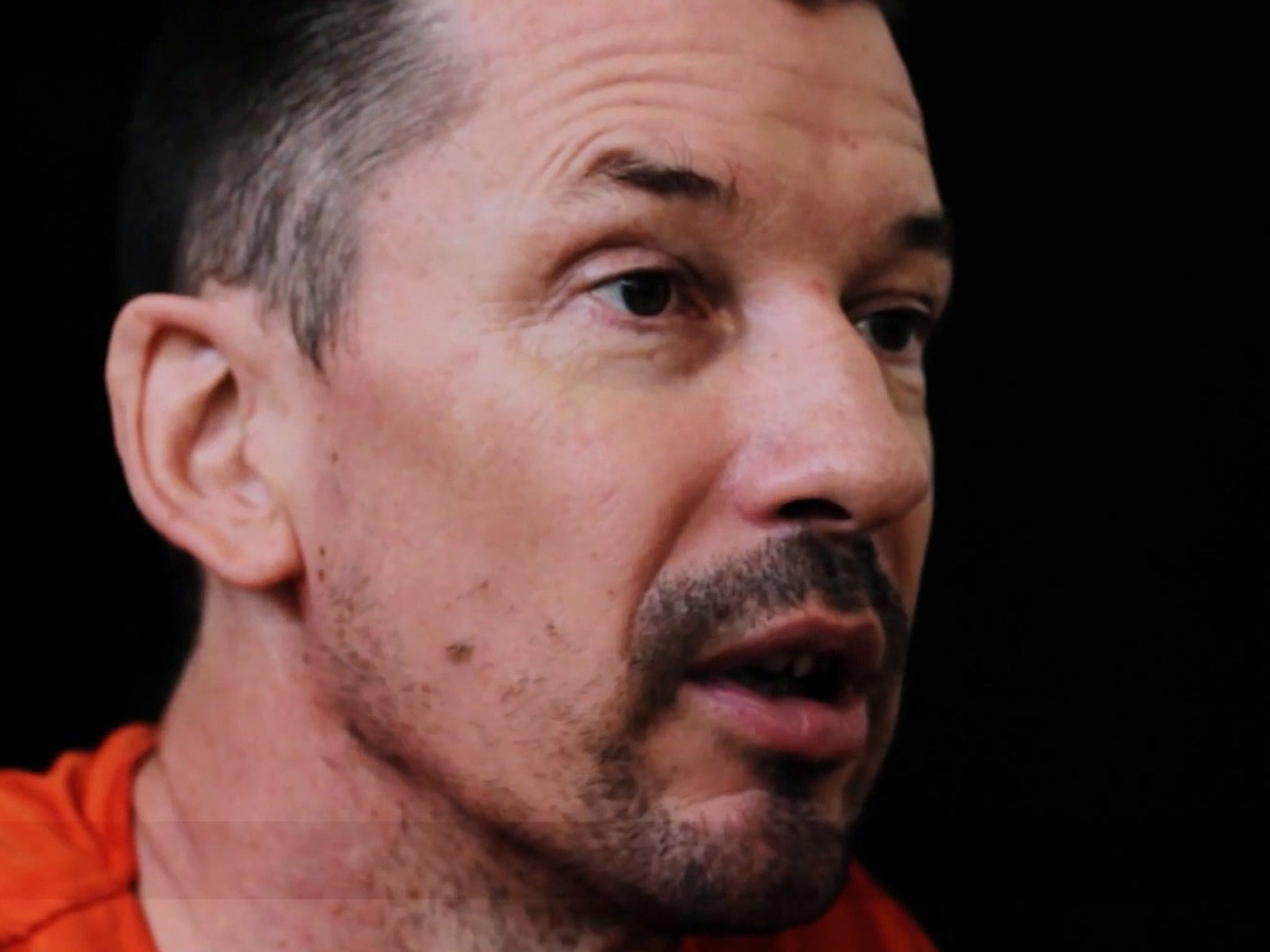

John Cantlie: He was caught while going back to see the fighters who freed him

Kim Sengupta describes the remarkable sequence of events that led to the capture – and recapture – of journalist John Cantlie

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In July 2012 journalists were rushing to the Turkish border to head into Syria. The civil war was on the turn, it was felt. The rebels were pushing into Aleppo. A bomb in Damascus had killed some of the regime’s most senior security officials. Bashar al-Assad was on the retreat.

As we prepared for our journey, there were concerns about two freelance photojournalists, John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemans, British and Dutch respectively, who had gone missing after crossing over. Fellow journalists worked hard to find him. Among them was the American Jim Foley, who would later be kidnapped, with Cantlie, in another journey into Syria. A terrible sequence of events followed that would lead to Jim’s murder and John’s appearance in the Isis video today.

Cantlie and Oerlemans had not gone far across the frontier when they disappeared. This was long before the kidnapping of journalists and aid workers became widespread. At the time the jihadists were very much a minority, with little influence, and the rebels were, on the whole, grateful the media were there to record the atrocities of the regime.

We tried to do our bit to find Cantlie and Oerlemans: a group of opposition fighters who took me into Aleppo said they were trying to free them and a rescue took place about a week later. But others had made similar claims and there were confusing and contradictory versions, both of the abduction and of what happened subsequently.

What struck us at the time was the account given by the two journalists that their captors were not Syrians, but British Muslims, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis. Foreign fighters were a rarity at the time: in Salheddine, Aleppo’s violent front line, the local commander, Sheikh Taufik Shiabuddin, had asked me: “Where are these hundreds of jihadists from abroad who are supposed to be here?” They were to come, in their thousands, later.

Cantlie and I spoke about his experience back in London. He told me how he and Oerlemans were led into a trap, and how they were shot while trying to escape.

Foley’s family eventually spoke out after little progress had been made securing his release. Groups of Spanish and French journalists were released earlier this year by Isis in return, it is claimed, for huge sums of money. The US and British governments say they have a policy of not paying ransom.

Last month Isis released the video of Jim Foley’s murder. It subsequently emerged that the group had tried to extort money from his family for his release. Cantlie’s kidnapping continued to be unpublicised until the video today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments