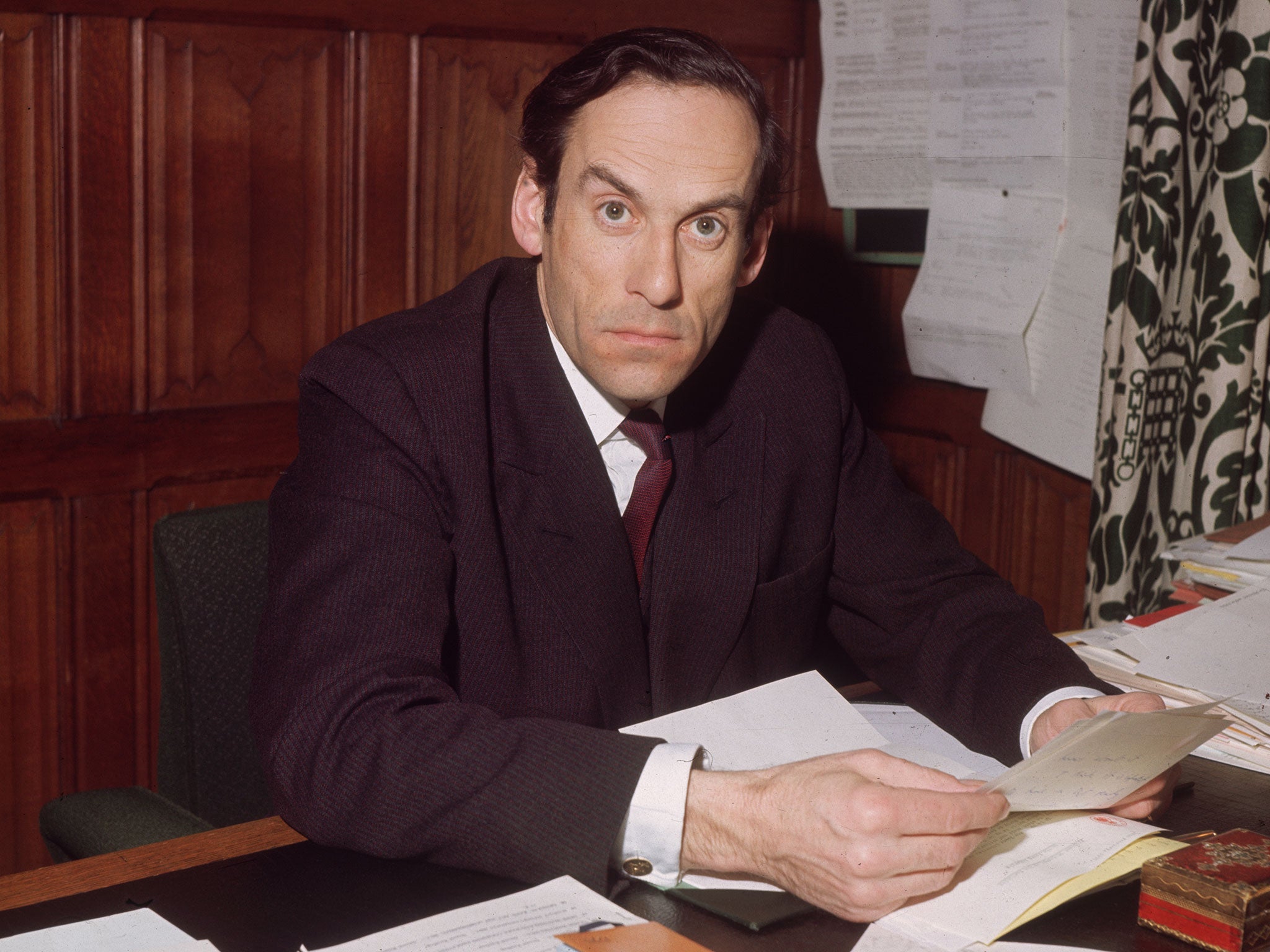

Jeremy Thorpe – the tragedy of a man who electrified British politics in the 1970s

Charismatic and brilliant, he gave the Liberal Party a stature that its successor would kill for in 2014

Before Cleggmania, there was Thorpemania, or something like it. Forty years ago Jeremy Thorpe was easily the most popular and energetic politician of his day, vaulting over road barriers and touring the coastal marginal seats that a revived Liberal Party was targeting in a hovercraft.

Like Clegg in the 2010 general election, Thorpe’s message was simple – the two old parties had failed and the country needed new politics and new leadership. In those days, though, the electoral system conspired more effectively against smaller parties, and Thorpe was rewarded with only around a dozen seats in the two 1974 elections for a fifth of the vote.

Still, he almost held the balance of power, and Edward Heath, as PM, offered him ether the Home Office or the Foreign Office (accounts vary) in a Con-Lib coalition government. Shades of Clegg-Cameron in 2010. The Libs would have been given a Speaker’s conference on PR – about as good as it was going to get.

It was heady, heady stuff. To me, as a school kid interested in politics, it looked like the future and I actually delivered some leaflets for the party in those elections, though it embarrasses me to admit to such precociousness. Thorpe was a hero to many more.

A few years later, when the Thorpe phenomenon had been supplanted by the “Thorpe Affair”, every Liberal supporter had to endure the humiliation of coming last in by-elections behind the National Front, losing councillors and deposits all over the shop, and being taunted with “how do you get three Liberals on a bar stool?” and other homophobic “jokes”. It was the 1970s, after all.

Not since the trial of Oscar Wilde had “gay” issues had such a public airing, and in the long run it might even have helped the cause of equality. At the time though, it was just cringeworthy. That Jimmy Savile was a prominent supporter, going so far as to front a Liberal party political broadcast, and Cyril Smith was one of the party’s main assets, just makes it all the more painful. Thorpe, in other words, very nearly broke the party that he had built up and which had done so much for him. The Libs were in worse shape then than they are even today.

In any case, his parliamentary colleagues, for a variety of reasons, refused to allow Thorpe to join a Lib-Con coalition with Heath. One good reason that some of them, notably David Steel, Thorpe’s eventual successor as leader, might have had their doubts about Thorpe during these years was their knowledge of damaging accusations and rumours about their leader. This was the truly tragic aspect to the Thorpe story – a flawed personality that destroyed a certain greatness.

The allegations that had been made privately to senior Liberal figures were soon to became public, and more lurid details and stories were added – about homosexual affairs and illegal sex acts in Thorpe’s Commons office; of stolen National Insurance documents; of a Great Dane named Rinka shot and killed on Exmoor; of assassins and pilots; of male models; of “biting the pillow” and Vaseline; of letters mysteriously declaring that “bunnies can and will go to France”; and of fugitive MPs living in Los Angeles taking payments from newspapers if their evidence against Thorpe and others came up with the “right“ verdict – the birth of “cheque book journalism” and an early omen of the dodgy habits that would one day envelop Fleet Street. Heady stuff, in all the wrong ways.

Thorpe, former party leader and privy counsellor, nearly Cabinet minister, was acquitted of the charge of conspiracy to murder – an amazing thing to contemplate even at this distance. Not long afterwards, Thorpe found himself having difficulty doing the buttons up on his shirt: Parkinson’s. A cruel disease, it made Thorpe’s later years and his fall from grace even more poignant, and he found it more difficult physically to take part in public life, which he had clearly always adored, right from his show-off days at Trinity and the Oxford Union, complete with fancy floral waistcoats and other of the Edwardian accoutrements and dandified sartorial habits he kept up right to the end.

I saw him occasionally at functions and, even with medication that ameliorated the symptoms of Parkinson’s, his voice was often too faint to make out. He would write to successive leaders with suggestions and ideas, all very thoughtful and helpful, especially on the pet topics of electoral reform. He was still a shrewd political observer.

But whenever it was rumoured that “Jeremy” was planning to make an appearance at Liberal Democrat conference the leadership shuddered and did whatever they could to deflect attention from his activities. There was good reason why the old boy was never offered the usual knighthood or peerage for his services, and he was, more or less, shunned, at least on the political level.

A slim volume of memoirs published a few years ago said nothing of value about the Thorpe Affair, and confirmed he was never going to tell the full story. They did, though, remind one that Thorpe had all the right instincts politically – an early pioneer of anti-colonialism and opponent of the racist regimes in South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), he once advocated bombing Rhodesia to bring the rebel regime there to an end. He wanted our political parties to work together in the national interest; for unions and employers to do the same in the economy. He wanted a fairer, freer society. He wanted a united Europe – openly so. In the end, though, all he did was let a great many people down, himself most of all. Tragic.

The writer is a former press officer to Paddy Ashdown

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments