It was always assumed that the poor were hard working. But that has ceased to be true

To revisit Richard Hoggart's The Uses of Literacy is to see what we have lost

I first read Richard Hoggart’s The Uses of Literacy a million years ago, when I was in the sixth form and it was a fashionable and influential study of working-class culture. I picked up a copy the other day, and it is still readable: a clearly-written blend of personal experience, a deep knowledge of the popular press and lightly-worn academic references – sociology as it ought to be.

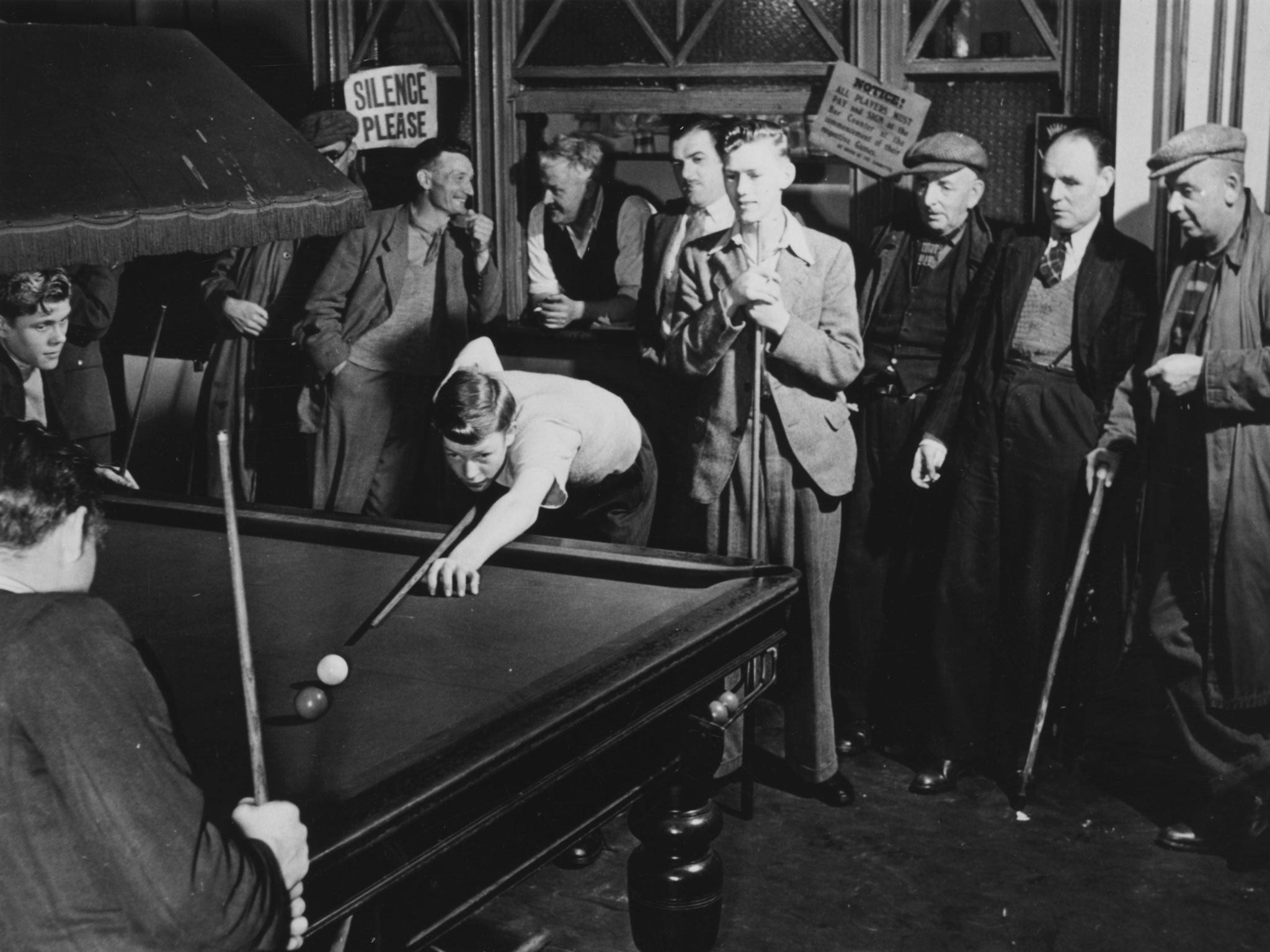

Mr Hoggart describes a way of life that was the despair of Marxist intellectuals over the decades. It had enabled those who were part of it to come to an accommodation with the demands of an industrial society. In Eric Hobsbawm’s phrase, the workers of the early industrial revolution often responded to their conditions with dreams and violence. By the 1950s, everything was gentler. This may not have satisfied those seeking a socialist revolution, but it did mitigate the potential harshness of a social order in which status would have wholly given way to contract.

Although conditions were often hard, the people he describes had evolved a sustainable way of life which had its pleasures, including self-esteem. There was a distinct sense of “Them” and “Us”, but “this is not the ‘Them’ of some European proletariats, of secret police, open brutality and sudden disappearances.”

The culture was essentially defensive. “Home is carved out under the shadow of the giant abstractions; inside the home one need be no more aware of those outer forces than is the badger under his mountain of earth.” Throughout the book, there is a sense of “a dense and concrete life” that is solid and dependable and which will protect the inhabitants from change.

That was entirely misleading. It was as if Richard Hoggart had written a guide to the stagecoach industry, in 1825. His book was published in 1957. Within a few years, the culture and the society which he describes were under mortal threat. The Uses of Literacy takes it for granted that life would be based on the eternal pillars of work and marriage. By the 1960s, both were on their way to resembling Ozymandias’s statue, while the culture in a broader sense was helpless to resist a barbarian invasion. There are no references to “television” in the index, though there are a couple of cursory mentions in the text. Our author had no idea how disruptive this infant medium would prove.

The badgers’ setts which Mr Hoggart extols were infiltrated by TV. Until then, a skilful workman who was also active in various local bodies could not only earn extra money: there would be accretions of status. It might not enable him to live like “Them” but they were separated by an unbridgeable social chasm. It was enough to earn respect from “Us”. Once television bombarded the household with the insatiable demands and ambitions of consumerism, those small satisfactions lost their potency. The once-proud worker was made to feel inadequate.

His wife was made to feel dissatisfied. Up till then, the assumption was that after a brief flighty period, indulging in fantasies supplied by the goddesses of Hollywood, working-class girls would marry and settle down, becoming domestic goddesses, in a pre-modern kitchen with little money. Like their mothers and grandmothers before them, their role was hard work and limited horizons. Then came the infinite horizons of the small screen.

From the 1960s onwards, the divorce rate rose steadily. Religious observance declined, and the nature of work changed. Mr Hoggart describes “One of those deep caverns in Leeds where the engines clang and hammer ceaselessly and... men can be seen, black to the shoulders, heaving and straining at hot pieces of metal.” It is good that those jobs have gone – or at least been banished to the Third World. Most modern factory floors are thinly populated, by technicians in white coats operating computer-guided lasers. Much better for those who work in them – but what about those who lack the skills?

Over the past few decades, we have created a lumpen-proletariat, which is now nourished on welfare and day-time television and which brings up its children without fathers. Professor Hoggart did not try to romanticise away the harshness, austerity and narrowness of the old working class, but there were also values, which have been lost. That has created social problems, which no one knows how to solve. John Major dreamt of a country at ease with itself, which would manage to harmonise the social stability of the 1950s with the economic dynamism of the Eighties. It remains a dream.

The disappearance of the Hoggartian working class had another consequence. The Marxists despised its stolidity, and saw its small “c” conservatism as a huge obstacle on the road to socialism. But it was a vast moral reservoir for the Labour movement. Even among middle-class socialists, there was a pervasive sense of the moral superiority of manual labour, as exemplified in the heroic personality of Ernie Bevin, and a belief that the party on the workers’ side had an absolute claim to the moral high ground.

That would have been true of John Smith, and Gordon Brown. In between them came Tony Blair, the ablest practical psephologist in modern British politics. He understood that it was not enough to build a coalition of the dispossessed. In Peter Mandelson’s immortal words, new Labour had to persuade the middle classes that there need be no limit on their aspirations: Labour was entirely relaxed about their becoming filthy rich. It was as if he had launched a dambusters’ raid on the moral reservoir, and for Ernie Bevin, read John Prescott. The water has been pouring away and the current front bench has no solution.

Indeed, it has another problem. I have just finished A Man of Parts by David Lodge: a jolly good read, like all his books. It is about H G Wells, and brings out his central importance in British intellectual life just before the First World War. Sexual life also: Wells was an eloquent advocate of, and a regular beneficiary from, female sexual emancipation. Lenin said that communism was electrification plus Soviets. For Wells, it was science plus contraceptives.

He and his fellow Fabians were confident in the inevitability of a gradualist, non-violent progress to socialism, for two reasons. First, they believed in the beneficent power of the state, assisted by science and technology. Second, they argued that under the existing social order, the idle rich were squandering resources which should be used to alleviate suffering.

We know better. If the 20th century has one lesson to teach us – apart from “do not follow my example” – it is the need to curb the power of the state, and to ensure that it does not destroy individual freedom, prosperity, democracy and the rule of law. As for the idle rich, Hitler put an end to them. In 1939, Bertie Wooster and his chums joined up. Most of them fought surprisingly well. After 1945, they were unable to resume their old ways; post-war taxation made that impossible.

The disappearance of the idle rich deprived the socialists of another moral weapon. The Fabians, and the Hoggartians, assumed that many poor people were among the hardest working members of society. That has ceased to be true. These days, it is Mr Mandelson’s filthy rich friends who put in long hours at their counting houses.

Wells assumed that the book-reading classes were generally seeking – and would certainly find – arguments for socialism. So, implicitly, does Richard Hoggart. That is no longer the case, and anyway, the old arguments no longer work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks